Even if GW pulls together an unlikely string of wins this week to write its own Cinderella story, it still would not live up to the drama and consequences of the program’s first spell of postseason magic two decades ago.

That’s because the 1993 Colonials team – which improbably went from last pick in the tournament to a Sweet 16 finalist that stuck with Michigan’s Fab Five down to the final minute – didn’t just stoke a fan base and generate national excitement. It helped change the University for good.

After the team’s March Madness run, which was the program’s first appearance in the tournament in 32 years, undergraduate applications shot up 23 percent. The athletic success branded GW with more name recognition, setting the stage for a University with higher selectivity, more tuition dollars and plans of campus expansion.

“GW, from an athletic point of view, had never experienced that kind of notoriety or success,” said Robert Chernak, who oversaw the athletics department for 24 years as a top administrator. “From an economic point of view, you could never afford to buy the kind of publicity GW was receiving nationally.”

The team, led by head coach Mike Jarvis and Nigerian seven-foot-one center Yinka Dare, toppled University of New Mexico and Southern University in the opening NCAA rounds that year. The New York Times noted in its game summary that without Dare, “George Washington would not be confused with Georgetown today.”

After going down early to Chris Webber’s University of Michigan in the Sweet 16, GW battled back to take the lead in the second half, before the Wolverines’ star players became too much to halt.

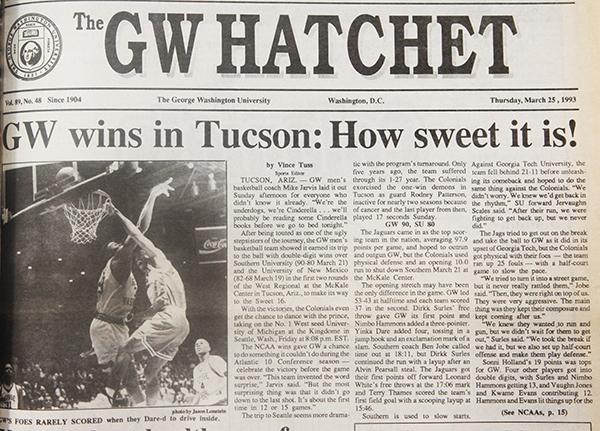

The week after the loss, a front-page Hatchet headline blared: “Admissions benefits from Colonials’ wins.”

The moment in the spotlight made GW a national Cinderella story – 1993 version of Florida Gulf Coast University, which busted brackets last year and generated name recognition for the small school. To capitalize on its moment, GW invited television and radio stations to broadcast from Marvin Center watch parties.

“We made as much of a fuss as we could,” former University President Stephen Joel Trachtenberg said in an interview.

Universities across the country have burst onto the national scene – improving selectivity, fundraising and branding – by seizing newfound athletic success. The phenomenon even has a name: the Flutie Effect, after the buzz Boston College generated after quarterback Doug Flutie’s Hail Mary against University of Miami in 1984.

Doug Chung, a Harvard business professor, published a study last year that showed applications increasing by 18 percent at schools with sudden college football success. To reach the same number, a school would have to lower tuition by nearly 4 percent.

The research backs up the strategy put forth by Trachtenberg and Chernak two decades ago, who early in their tenures made athletics a priority for the first time in years.

“It was pretty clear that they were going to put an emphasis on sports. It was clear this was one of their strategies to get name recognition. A Sweet 16 clearly did that,” said Chris Deering, a political science professor who was an administrator under Trachtenberg in 1993.

Now, GW’s name is mostly solidified among the ranks of selective colleges. But the on-court success that started in 1993, which Chernak said created “inertia” for the University as a whole, was part of an early wave of change at GW. Then, the University enrolled only about 1,300 freshmen – about half the size of its current class.

More applications and selectivity meant a rising academic prowess, punctuated by GW’s first appearance in the U.S. News & World Report top 50 rankings in 1997. Higher enrollment meant more tuition dollars to spend on faculty hires and required the aquisition of the Mount Vernon Campus that year.

Michael Freedman, who led Trachtenberg’s public affairs operation, said GW then doubled down on the renown of its location, finally penning the phrase “four blocks from the White House” on every press release. After the 1992 election, GW also housed the temporary media hub for a Clinton administration waiting to move to the White House, putting a stronger spotlight on Foggy Bottom.

“You could begin to tangibly see the differences being made at the institution. After we had things like the NCAA run, Trachtenberg once said to me, ‘Now it’s time to transform this series of flashing lights into a steady glow,’” Freedman said.

The wins also made for a happier campus and alumni base, Chernak said, allowing the University “more margin of error for things to go wrong.”

“You’re proud to wear a shirt that wears George Washington,” he said. “It’s fleeting, you’re not necessarily going to win a game or you might win a couple games, but you got a whole week to celebrate before you get on the court.”