The University’s admissions page paints the experience of attending GW as “living and learning in the heart of D.C.” For some students, this is GW’s draw. And for many more, it’s their reality. But as one of the most expensive schools in the country located in one of the nation’s most expensive cities, GW sells its students the idea of a rose-colored metropolis without sufficiently acknowledging how officials can make GW financially accessible for students, like addressing the exorbitant prices of housing or offering further resources.

GW keeps getting more expensive. The cost of on-campus housing increased by 3 percent this academic year — from $5,350 to $5,510 and meal plans increased by around $140 per semester. And while students pay these hefty prices to live in on-campus buildings, they still encounter major issues in their residence halls, from mold and ceiling leaks or water outages to accessibility issues like malfunctioning elevators. But the University never clarified why they bumped up housing and dining costs, sidestepping any progress toward reaching transparency on the steep cost of living on campus.

Private universities in 2023 saw a roughly 26 percent increase in tuition and room and board in the last two decades, outpacing the growth of median family income, which sits at 13 percent. But many universities do this intentionally, catering to wealthier students to attract high-paying families to their institution. Universities may also hike their prices to fairly compensate professors and administrators, whose wages often outpace inflation.

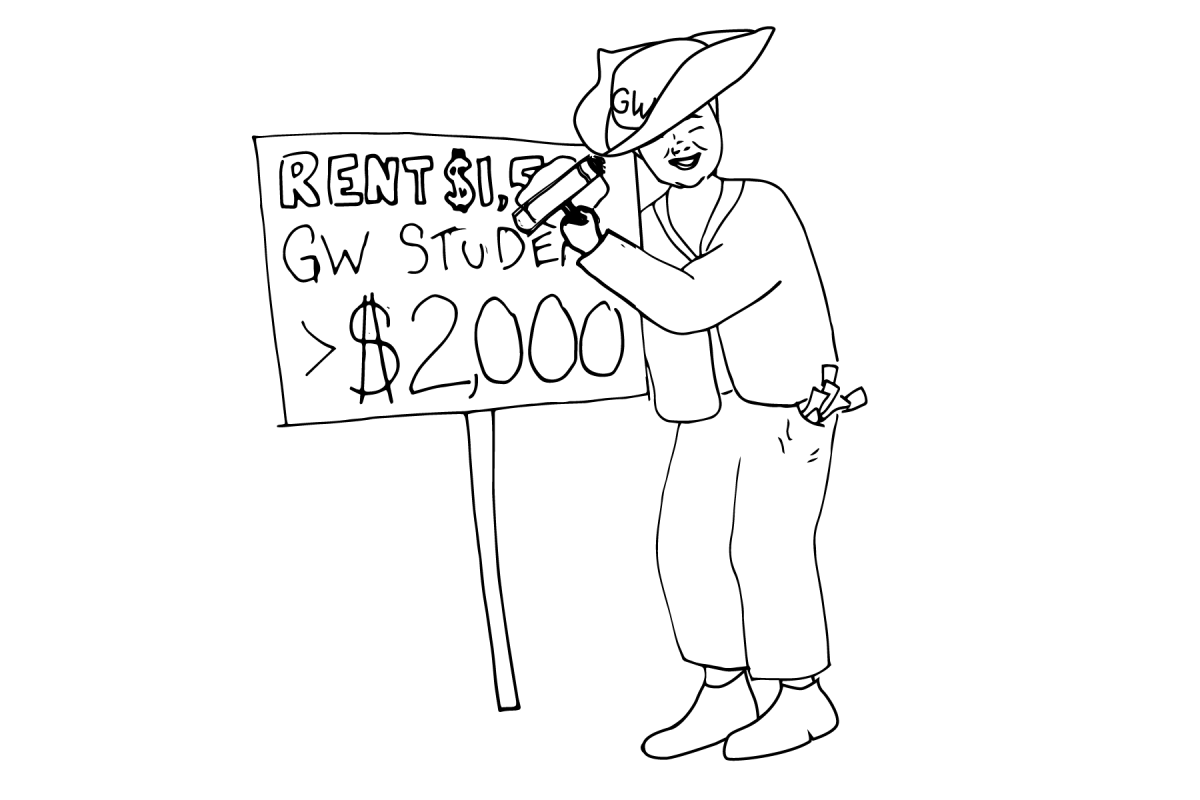

Especially considering the growing housing crisis in D.C., where rent prices have increased by almost 11 percent since 2019, officials should be prepared to break down the root of the uptick for on-campus housing costs as off-campus housing alternatives become more expensive. Many students seek off-campus housing as a reprieve from the headaches of GW facilities, turning to pricier options that may give them more of a bang for their buck. Last year, the average D.C. studio apartment totaled around $1,847, and earlier this year, landlords in Foggy Bottom faced a lawsuit for allegedly colluding to increase rent prices at apartment buildings near campus like The Statesman and 2400 M Street apartments.

Inflated housing costs are a symptom of multiple issues. For one, there aren’t enough homes to keep up with the demand across the nation, including D.C., making any available living spaces even more expensive. In the D.C. region alone, officials would have to build 87 homes every day to keep up with demand, according to a Washington Post analysis. If off-campus housing proves to be too costly and scarce, prompting students to rely on the University’s on-campus options, it makes sense why the rise in demand has made GW’s housing more pricey.

The increasing unaffordability of local homes and GW Housing incentivizes real estate investments for the students and families that can afford it. Affluent parents of GW and Georgetown students have been purchasing $2 million homes in cash in D.C. for their children in college. Parents invest in the market and realtors justify their prices, soaring into the millions in some parts of the District. The high population of students in Foggy Bottom, some of whom have parents willing to rent or even buy extortionate homes within the neighborhood, makes the area financially out of reach.

Foggy Bottom used to be a low-income neighborhood before GW moved in and began renovation of historic properties, furthered the expansion of campus and prompted the construction of neighboring apartment complexes. Most of these properties acquired throughout the years were bought for affordable prices from working- and middle-class communities, eventually displacing low-income families and the once-predominant Black community in the neighborhood.

Between 1960 and 1970, the Foggy Bottom population dropped around 25 percent, pushing out the remainder of residents who couldn’t keep up with the rising prices. And now those homes or buildings go for millions of dollars, as GW owns more than $400 million in taxable property and in 2018 paid around $8 million in property taxes. GW students may be here for only the time of their education, but the residents of D.C. and Foggy Bottom are the ones that are here to stay.

Last year, GW decided to drop the on-campus residency requirement for third-year students, ultimately placing upperclassmen and sophomores on the housing waiting list or rejecting them for housing when officials failed to meet demand for residence hall spaces. Officials claimed they didn’t see strong demand from third-year students to stay on campus, stating that 25 to 35 percent of students opting to live in off-campus apartments or houses. But later in the meeting officials said they planned to add more beds to some halls to keep up with demand.

With upperclassmen left without housing assignments, many scrambling to find off-campus options with manageable rent or travel costs, GW should have sprang to action, providing advice on how to navigate D.C. leases, offer financial assistance for those forced to move off campus or simply provide explanations for why GW Housing was unable to accommodate their students.

GW should take strides to make housing more accessible for students, whether it’s by mitigating on-campus costs to accommodate students from different socioeconomic backgrounds or providing assistance and support for students navigating the D.C. housing market for the first time. As the landlord to tens of thousands of students, GW could introduce rent-controlled properties to offer consistent prices for students amid a turbulent housing market.

Even breaking down housing costs and dissecting the upticks students are seeing on their tuition bills could remove the veil from the reality of D.C. real estate that even the University is bearing the brunt of. It’s easy to misinterpret GW’s housing prices when it’s not explained. And it’s useful and normal to see a breakdown of costs when making these crucial economic decisions.

The University tells us that attending GW means living in our nation’s capital, giving us those “#OnlyatGW,” moments and the least the University can do is try and live up to its promise.

The editorial board consists of Hatchet staff members and operates separately from the newsroom. This week’s staff editorial was written by Opinions Editor Andrea Mendoza-Melchor based on discussions with Culture Editor Nick Perkins, Sports Columnist Sydney Heise, Contributing Social Media Director Anaya Bhatt and research assistant Carly Cavanaugh.