Correction appended

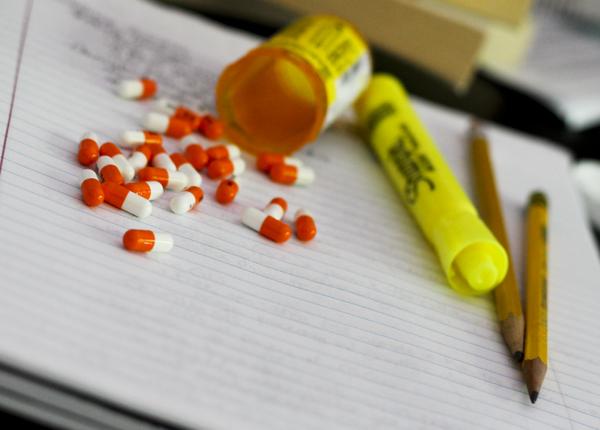

With more and more students reaching for ADHD drugs to boost their studying focus, GW doctors are looking to add steps and procedures this fall to reduce prescription drug misuse on campus.

Student Health Service, the only University office with psychiatrists, could require students to undergo behavioral therapy sessions next year before they can refill prescriptions for medications like Adderall, Vyvanse and Concerta, instead of requiring short meetings with a primary care physician.

The medical services department is also in talks with the University Counseling Center to conduct in-depth psychological evaluations on campus instead of pushing students to off-campus practitioners, SHS senior psychiatrist Donna Ticknor said.

And after Ticknor noticed a sharp rise in recent years in students seeking an ADHD diagnosis – and the accompanying amphetamine prescription – this year SHS will start to track the specific number of evaluations for the disorder and their outcomes.

Ticknor said she and the other SHS psychiatrist evaluate about three students a week who say they think they have an attention deficit disorder.

“On one hand, people are much more aware of ADHD, so I think more people are legitimately coming in and asking if they have ADHD,” Ticknor said. “But that being said…there are some students who we are certainly concerned are faking some symptoms.”

Experts say the medical dangers of misusing ADHD drugs are real. People who abuse the amphetamine-based drugs may suffer from sleeping problems, anxiety, depression and psychosis, according to the National Institute of Health.

And nearly 60 percent of drug-related deaths in 2010 involved prescription drugs, according to a 2013 report conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. GW Law School student John Hroncich died last year due to a lethal mix of heroin and Adderall.

Despite the adverse risks, a 2008 University of Kentucky study pegged the number of students using ADHD drugs without a prescription at 34 percent, based on a survey of that university’s students.

Tests for attention deficit diagnoses at GW are rigorous, typically taking six to eight weeks for a prescription, and include screening questionnaires, an hour-long meeting with a psychiatrist and a full psychological evaluation with a psychologist before a prescription can be obtained. But Ticknor said she believes more can be done to make it especially difficult for students to illegitimately obtain or refill an ADHD prescription on campus.

Some primary care doctors prescribe ADHD medication after a patient fills out an evaluation form during a 15-minute visit, Ticknor said, and she wants to ensure the process on a college campus like GW remains much more rigorous.

“The problem with the rating forms is that they are also shown to be very easily faked if someone really wants to get medication,” Ticknor said. “But there is no foolproof way of knowing for sure.”

And while the in-depth psychological evaluations are much more difficult to dupe, neither GW’s Student Health Service nor the University Counseling Center have psychologists on staff who conduct psychological evaluations needed to diagnose ADHD.

But despite the University’s psychiatric oversight of students with prescriptions for ADHD medication, Ticknor recognized that much of this drug abuse on campus is beyond their control.

“We can look at how we prescribe these medications, we can look at how we monitor these medications, but the truth is a lot of students get these medications from somewhere else,” Ticknor said.

Instead, Ticknor said SHS has ramped up their efforts to educate students about the risks of abusing the ADHD drugs. Over the past year, students prescribed the drugs have been required to sign a contract with an SHS psychiatrist explaining the medical and legal risks of selling or sharing the drug with classmates who don’t have a prescription.

A sophomore, who asked not to be named because not all of his friends know he has ADHD, said that he has experienced side-effects of the ADHD drugs he was prescribed despite undergoing thorough evaluations since he was in 7th grade, and wouldn’t risk taking a prescription drug without medical testing.

“It’s a huge trial process to get the right medication,” said the sophomore, who has gone through trial-and-error with multiple different doses and medications. “I’m taking my medications to help me and to be able to act like a normal person, and be able to pay attention like anybody else.”

Selling these drugs or possessing them without a prescription can result in felony charges, and SHS doctors and psychiatrists will not refill a prescription for students who claim their medication was lost or stolen — an increasingly common practice at other colleges and universities.

“We know that, unfortunately, people who are trying to make a few extra bucks will sell their medication and come back in because they need it as well,” Ticknor said.

As more universities are putting the “study drug” phenomenon under the microscope, some universities are even chalking up the unauthorized use of ADHD drugs as cheating.

But while Duke University added “the unauthorized use of prescription medication to enhance academic performance” to its code of academic conduct, GW’s director of Student Rights and Responsibilities Gabriel Slifka said that GW has no such plans.

Slifka, whose office absorbed the Office of Academic Integrity late this semester, said the University’s “comprehensive approach” to the unauthorized use of prescription drugs would not change despite the merger.

This post was updated June 17, 2013 to reflect the following:

The Hatchet previously reported that the University Counseling Center does not employ psychologists. There are psychologists at the center, but they do not diagnose ADHD. We regret this error.