A short walk from Union Market, where vendors sell charcuterie and gelato on weekend mornings, is the D.C. Youth Services Center, a brick building with tall, beige walls.

The center houses about 60 incarcerated juveniles who walk in single-file lines, hands behind their backs, to move between cinderblock rooms. Most of them await trial in D.C. Family Court.

Justice for Juniors is a coalition of students from GW and other D.C. universities that aims to end repeat offenses by minors. The volunteers tutor incarcerated youths twice a week, in the Marvin Center and in a city detention center, sharing news articles and encouraging them to think critically.

The program is run by Chaplain Jonathan Siafa Johnson, a Baptist minister on GW’s Board of Chaplains.

Last week, on a visit with J4J volunteers from Catholic University, a guard checked the neckline on girls’ shirts and made sure everyone was wearing closed-toed shoes. Before students entered the cell block, officers counted the pencils they brought in the room to ensure the same number leave. (They can be sharpened and used as weapons or for self-harm.)

He reminded them that these boys — most incarcerated youths are male — have done and seen things beyond the average college student’s comprehension.

“Their experience far supersedes your own,” the guard told 11 Catholic University students and two local ministers before being led through heavy metal doors, one of which must be closed before the other opens. The center is one of 10 juvenile incarceration centers in the District.

A violent environment

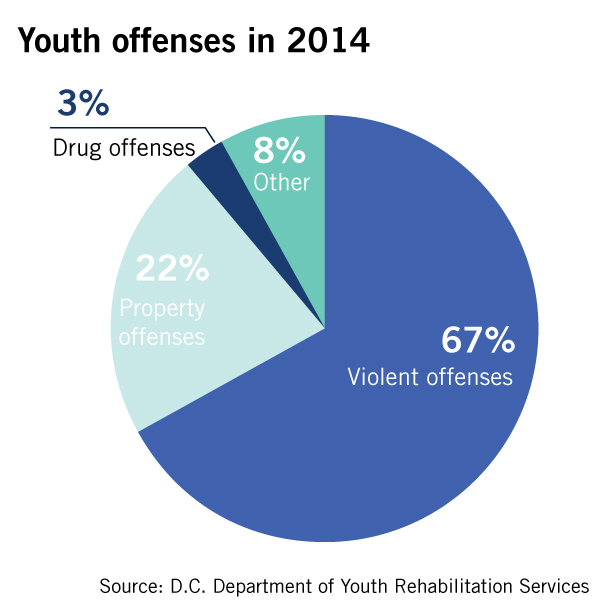

Last year, two-thirds of charges against juveniles were violent offenses, which includes weapons offenses. Forty percent of newly committed youths were charged with felonies, according to the Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services.

A tenth-grader from D.C., who spoke on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the topic, is completing his high school’s required community service hours with J4J.

He said he felt it wasn’t until an American University alumnus — whom he called an “innocent bystander” — was killed two weeks ago near the Shaw-Howard Metro Station that media scrutinized the summer’s uptick in gun violence. This summer, his friends had run from gun shots in Southwest D.C., but that violent crime in low-income areas usually doesn’t grab headlines because it’s viewed as the status quo.

“People dying throughout the city and ain’t nobody speaking up. Like, you ain’t gonna hear about the guy who got shot in his head over there by [Martin Luther King Jr. Ave. SE],” he said. “Stuff go on, and they don’t shine the limelight on [it].”

Juveniles in the D.C. system are often raised in an environment dictated by some combination of gang violence, domestic troubles and a poor school system. The tenth-grader explained that, in the neighborhoods in which these boys grow up, it is often easy — and sometimes necessary — to find a gun to call one’s own.

Bridging the gap

Participation among GW and local college students has wavered since it started in 2006. Johnson said he prefers to be low-key about initiatives like J4J. Currently, there are only about five GW members, though Johnson said that the group hopes to recruit 100 volunteers this year so that students can develop mentorships with juveniles once they are discharged from District custody.

He said GW students often “go through shock” when they visit the center, a 20-minute Metro ride from campus, because they are faced with a world that’s a far cry from Foggy Bottom. Johnson said the juveniles have “survival questions” to answer — which can make it difficult for tutors and juveniles to connect.

“They want to know how to go to college when you’re poor,” Johnson said. “How do you graduate from high school when you’re five grades below reading comprehension? When the father’s in jail and your mother’s in the hospital, who takes care of you? Provides food for you? Where do you go when you’re going to be evicted and your mother can’t work?”

In 2014, 99 percent of newly committed youths were black and more than half were 16 years old or younger, according to the Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services, which updates its website weekly to reflect demographic shifts.

When senior Ryan Tom, a member tasked with increasing the group’s visibility, comes back to school this semester, he hopes to be one of many volunteers walking through a metal detector and stowing his phone in a locker once a week. Tom only found out that the group exists through a listserv for criminal justice majors just last semester.

“It’s hard to be in the system already and to be so young. It puts an enormous amount of pressure on you,” Tom said. “It’s important to hammer into their minds that they’re young, that they have their lives ahead of them.”

Over the summer, Tom said GW gave Justice for Juniors a $1,000 civic service grant, which he said the group will use to transport volunteers from campus to the detention center.

Sometimes, when they discuss the future, Tom said the juveniles say they want to be football players, presidents or lawyers, though in a recent session in the Marvin Center, most of the boys said they aspire to be engineers. Some may have far-fetched goals, but Tom thinks that’s a good thing.

“High-reaching dreams means they still have hope,” he said.

‘Something that’s better’

The volunteers visit the detention center on Monday evenings. In the cell blocks, which the center calls pods, about 10 boys sleep in separate rooms. Their metal doors open up to a common room with a few tables for the boys — dressed in collared shirts, plastic slippers and gray sweatpants — and visitors to sit around.

One boy, who was folding laundry when the students walked in, looked amused at their hesitant expressions. Incarcerated juveniles cannot be named.

“I don’t bite,” he told them.

In pod D-200, the Catholic University students — working on a community service initiative — helped the boys take a survey about religious devotion. One of the prompts asked if they would rather read about devout people who build homeless shelters or religious extremists like suicide bombers.

One boy, baby-faced and a better reader than most of his peers, said that he wanted to learn about the former.

“I’d rather put in my mind something that’s better,” he said. Then he joked about lyrics to a Drake song.

At the end of the 60-minute session, the boys asked if the volunteers would be back next week.