GW’s research profile needs a spark, and officials are betting that doubling the money schools can keep from research subsidies will do the trick.

The University will now give schools back 27 percent of the money the federal government doles out as bonus funding for research that qualifies for the subsidy. That’s an important step for a school that wants to improve its research reputation over the next decade.

Faculty have conducted more research over the last several years, but as federal funding has slowed, officials have looked for ways to encourage more professors to boost their research prospects. The bonus funding, known as an indirect cost recovery, pads the University administration’s central budget, and schools get to keep a slice for their separate budgets depending on how much faculty can pull in.

Schools used to receive 12 percent of the money back from research through the incentives program run out of GW’s research office. Growing that amount will help GW boost its overall research capacity and motivate professors to do more research, said Vice Provost for Budget and Finance Rene Stewart O’Neal.

“Our research portfolio is growing at an aggressive rate. But still, in comparison to peers, it is relatively small,” Stewart O’Neal said.

But for most faculty, the incentive to get a grant is the chance to conduct groundbreaking research – not the money it brings back to the school, physics professor Gerald Feldman said.

“The incentive is the specific project,” he said. “It’s good but the amount of money we accumulate from recovered costs must be small compared to departmental budgets. It’s like a little icing on the cake, you have a little more or a little less.”

Henry Nau, an international affairs professor, said though the increase in cost recoveries would help a school, the only real impact would come if it trickles down to faculty members doing research – which he said doesn’t happen much now.

He said the Elliott School of International Affairs has a “very paltry policy” for sharing the subsidies with faculty, and that he typically gets back about $600 or $700 each year from his $100,000 grants that bring together members of Congress and leaders from South Korea and Japan.

“A lot of faculty members say it’s so small it doesn’t matter,” Nau said. “It takes away the incentive for faculty to raise money.”

Motivating professors to do more

Officials count on indirect cost recoveries to help cover the overhead costs of projects that otherwise could be too pricey. The money can go to the nuts and bolts: paying for equipment, hiring staff and keeping lights on in laboratories.

The University would not release the total amount of cost recoveries it brought in last year, but in the past officials have been confident they could pull in at least $30 million in total eligible research funding. That would translate to an added $9 million per year to help pay for the Science and Engineering Hall.

Leo Chalupa, vice president for research, said GW hopes to grow the amount it brings in through indirect cost recoveries by about 3 percent each year, which he said would stand up well to a “bad funding climate nationwide.”

Last year, the University brought in nearly 5 percent in indirect cost recoveries, above GW’s target, Chalupa said. The University’s research expenditures also increased 11 percent last year, beating officials’ expectations.

“The reputation of this University in every aspect has gone up higher and higher and higher,” Chalupa said.

But as GW focuses on research, it will take more effort to keep up with officials’ aspirations, said Christopher Cahill, a chemistry professor.

He also said many agencies have increased compliance requirements and the amount of paperwork faculty members need to complete, adding an extra layer to their research responsibilities as GW pushes for more.

“One of the challenges in all of this, with the research enterprise at GW, is the aspirations of the faculty have blossomed and maybe outpaced infrastructure,” Cahill said. “[The research office] has had to catch up to very hungry faculty and a climate of increased demands in compliance and bureaucracy nonsense.”

Making the system work

Stewart O’Neal said each dean will get the money to invest back into its research infrastructure, but administrators are “not prescribing how that’s done.” She said the new budget model, which will allow the University to predict costs five years in the future, will help GW distribute the funds.

“We don’t want to micromanage how each dean runs and manages their research portfolio. We provide resources, let deans know expectations and then let them decide,” Stewart O’Neal said.

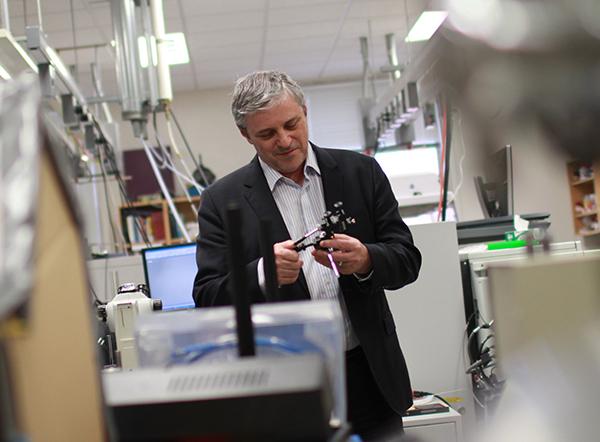

Akos Vertes, a chemistry professor, said the changes to the budget system to focus on research are “long overdue” for growing GW’s research capability. Vertes said he has seen the focus shift toward research – and larger grants – during his 23 years at the University.

“When I was hired, it wasn’t necessarily an expectation that faculty have active research programs that brought in external funding. By now I think that is the norm. That’s a very substantial change,” Vertes said.

Vertes received a grant worth up to $14.6 million in January to spend three years investigating chemical and biological threats like anthrax. That grant qualifies for receiving 52 percent of the grant’s value, and will add an additional $7.2 million to GW’s revenue stream.

Vertes said the current budgeting system makes it difficult to allocate resources for costs like graduate teaching assistants, who he said are “instrumental” to successful research.

“No matter what instrument one buys, and you can buy the best there is, if you don’t have the people to be able to operate it at that superb, expert level, it’s not going to help. I find myself dealing with personnel issues more than ever,” Vertes said.