When Henry Nau traveled to Chicago last May to promote his new book, GW’s alumni office set up a breakfast for him to meet with alumni and discuss his policy research.

Nau, a professor of international affairs, met about 30 alumni in a plush law office to discuss his latest book, “Conservative Internationalism,” and the graduates remembered what it was like to hear a lecture from a GW professor.

While Nau said he has only been to a few of those events, they’re one way faculty can show off how they’re moving the University forward, and re-engage alumni as GW increasingly reminds them to think about donating.

Across campus, faculty are mostly waiting to hear how they can be part of the University’s $1 billion fundraising campaign. As deans finalize their plans and travel schedules, they may look to engage certain faculty who could appeal to particular donors or demonstrate what types of projects their donation could help support.

“In some sense, all of your fundraising is a function of the quality of the University, and a large part of that is the quality of the faculty,” said Nau, who has taught at GW for about 40 years.

Michael Morsberger, vice president for development and alumni relations, said faculty have been engaged in fundraising efforts at smaller events, like presenting their work to advisory committees or alumni who support deans and typically donate regularly, or to connect development officials with alumni with whom they’re still close.

But with more than 1,000 full-time faculty members, Morsberger said it can be challenging to match individual professors with potential donors.

“I can’t put them all on the road, I can’t put them all in a magazine,” he said. “But we are trying to get a sense of where opportunities lie to support them and try to match them up as best we can.”

Nancy Peterman, an education and cultural institution fundraising expert at Alexander Haas, said faculty, especially department chairs, play an important role in helping deans set priorities before a fundraising campaign even begins.

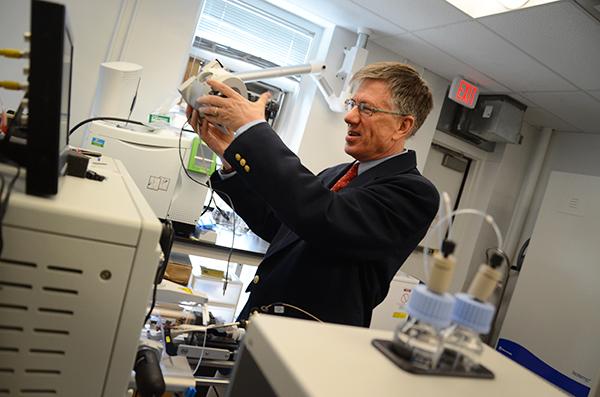

Once the campaign starts, faculty can help show donors why they should give to a particular cause, she said. Professors can bring potential donors into their labs or offices to show the direct impact their gifts could have.

“They’re the experts, they’re the reason the institution exists,” Peterman said. “It’s what happens inside the classroom that really makes the difference. This is why it’s just so important that we have the faculty available and meeting with donors.”

Half of what the University hopes to raise will support academic programs, like hiring new professors and launching interdisciplinary research institutes.

Faculty have started to become a regular group of potential donors, too, with donations from University employees reaching $22 million in 2013.

The development office hosts an annual reception for faculty and staff who have donated. Giving a gift themselves is often the first step in involving a professor in the fundraising process, Morsberger said.

Each school has set a goal for how much it aims to raise by the campaign’s end, ranging from $8 million for the School of Nursing to $225 million for the School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

The School of Business hopes to bring in $75 million, with $25 million for global programs and $15 million for advanced learning.

Charles Garris, an engineering professor and chair of the Faculty Senate executive committee, attended the campaign’s launch in June with other members of the group. At the event, he said he answered questions about projects within the University, like the move to the Science and Engineering Hall.

Still, the senate, which is made up of roughly 40 faculty members chosen to represent each school, has not been asked to take on a more significant role in the campaign, he said.

Garris said by having faculty across disciplines who officials can ask to meet with donors, the University is better prepared to explain particular causes, which is now a more common way to donate.

When faculty are approached to court a donor, they’re typically pleased because it could mean more resources for their department.

“I would say most professors are not necessarily approached unless a donor is identified in that area, but then the professors are wildly excited if they are,” said Garris, who has taught at GW for about 30 years.

Victor Weedn, chair of the forensic science department, said he was planning to start reaching out to alumni to cultivate donations, although that could be difficult for the small department from which most alumni don’t go into high paying jobs.

He said the department have yet to reach out to former students who have launched successful companies since graduating, since the department needs to diversify its income.

Weedn partnered the department with PerkinElmer Health Sciences, which has provided the department discounted rates on equipment and also donated to their lab to support the high-tech mass spectronomy lab.

The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences is hoping to bring in $100 million, with $25 million for endowed professorships and up to $10 million for faculty research support.

A $250 donation to GW’s largest college can support a student’s media project, while a similar-sized donation to the School of Engineering and Applied Science can support students launching a business venture through the business school’s competitions.

Robert Eisen, chair of the religion studies department, said he wasn’t surprised that chairs hadn’t yet gotten much direction on how they can contribute, since the campaign went public just this summer.

“I’d like to see money come into the department to teach students how it can be a vehicle for peace but these are all in my own little system,” he said.

Michael Nilsen, the vice president for public policy at the Association of Fundraising Professionals, said having a few key faculty members involved in sharing personal stories with potential donors is common for universities conducting a fundraising campaign.

Development officials will need to describe to professors why their role in a fundraising campaign is important though, he added, as raising money doesn’t typically fall under their job description.

“If you don’t have a lot of fundraising background, I think people can be pretty intimidated by the thought,” he said. “But you’re not necessary doing the fundraising, you’re helping to build the case.”

-Colleen Murphy contributed reporting.