If you noticed a lackluster selection while registering for classes over the past few weeks, you and I have something in common.

I found myself disappointed that dynamic classes in my major and minor were nearly impossible to find. Several course titles were just lists of nouns, like “Sexuality and Law” and the frustratingly vague “Approaches to Women’s History.”

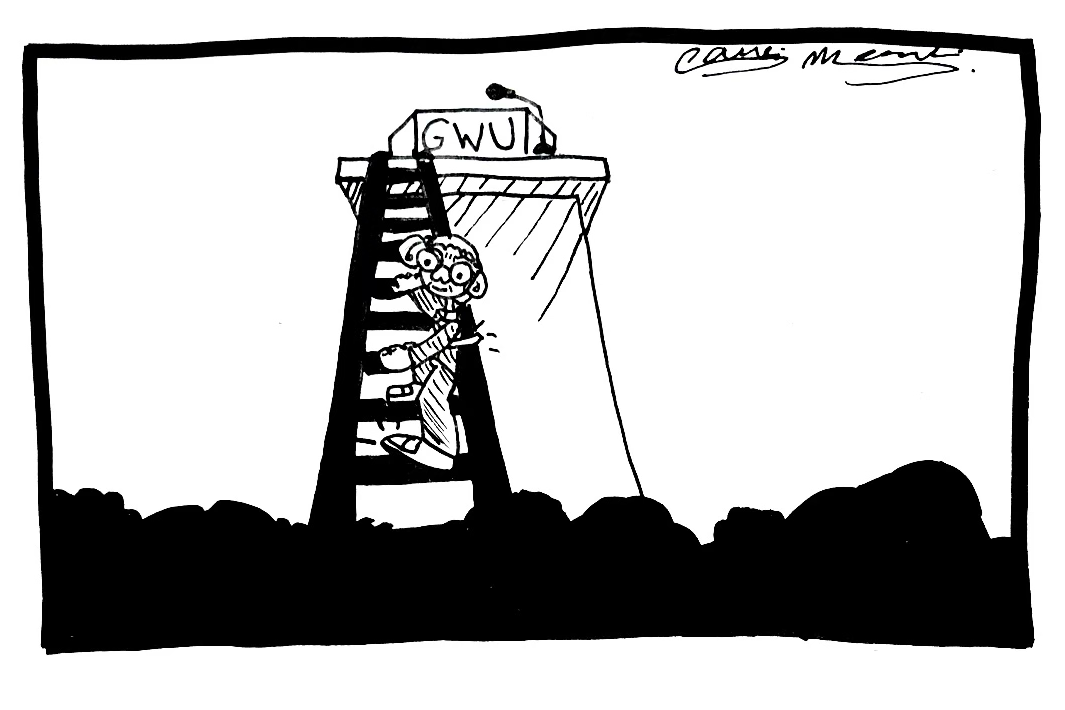

The New York Times featured last week 10 college courses “with a twist” nationwide, including The Art of Walking at Centre College and Extreme Weather at the University of Michigan. Would you be surprised if I told you GW didn’t make the list?

Although course offerings at other schools might seem strange judging strictly by their quirky titles, essential skills are often best learned from what one professor described to me as a “kitchen sink” approach. The class topics may meander, but students are actively engaged. And we all can find time to take a few wackier courses if they’ll pay off in the long run.

We have some strong professors at our school, as many students will attest. But the University seems like it would rather be known for its proximity to important people, places and things.

That’s one way to make a name for ourselves. Another is to be known for top-notch teaching, and one of the best ways to make that happen is for the University to allow professors to structure their courses around their individual areas of interest.

With the exception of one-off, heavily promoted options like a seminar with Ben Bernanke or José Andrés, the overwhelming majority of GW classes are same-old, same-old.

These classes tap into that all-too-familiar GW ideology of “it’s who you know” – they’re only unique because of our school’s ability to reel in “celebrities.” They’re gimmicks. And that’s not an ideal off of which any school should base its entire academic identity.

Professors can bring in the chief economist of the World Bank to teach game theory – giving students a one-of-a-kind experience – but departments should be just as driven to deliver those experiences every semester with the professors GW already employs.

A professor’s enthusiasm for a subject is a precious commodity. It can make or break a class for a student. Think about the best classes you’ve taken at college: They were likely memorable thanks mainly to your professor’s passion for the subject they were teaching. This is what the University needs to foster, appreciate and respect.

There’s one place where this is already done: dean’s seminars. Fifteen different lectures are offered by full-time faculty to freshmen in the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences each semester, with enrollment totaling about 300 students overall.

Assistant professor of American studies Dara Orenstein, who teaches the dean’s seminar “Zombie Capitalism,” admits her subject may seem narrow on its face, but says there’s a broader application to the topic.

“I’m fine with a sprawling, sometimes confusing conversation,” she told me, “because definitely part of my agenda is not to offer the neat and tidy lecture course.”

Even if a student isn’t particularly interested in the specific subject matter of a dean’s seminar, professors enthusiastic about their course are often more successful in teaching students a highly applicable, broader skill, like critical thinking or improved writing.

Several dean’s seminars classes take an interdisciplinary approach to appeal to a common denominator of students. Thomas Mallon, a professor of English, incorporates novels, films, poems and photography into his lecture, called The Assassination of Lincoln.

This reminds students “not simply to go at it down one avenue,” he explained, “because if you do that, I think you’re really missing something.”

The approach used by Orenstein, Mallon and others shouldn’t be restricted to 1000-level courses for CCAS freshmen alone. Classes at all levels, in all schools – even outside of the humanities – can be structured around a professor’s enthusiasm. It may take some work to restructure classes, but the work will greatly improve students’ academic experiences.

Professors shouldn’t be pigeon-holed into teaching a subject because it checks off some general education requirement on their students’ DegreeMAP records. These aren’t the classes that end up teaching us the most important skills, the skills we’ll use most for the remainder of our college careers.

Schools across the nation have made some efforts to improve the quality of teaching. Sometimes, learning fellows observe teachers and critique them; other programs invite professors to chat in groups about techniques that have worked for them. These may spur small improvements, but the most effective tactic is to let professors teach courses in which they are invested.

“You might not remember a ton from each class,” Orenstein told me. “But you might remember a question that clicked for you or a way of thinking.”

And at the end of the day, that’s the most important teachable moment.

Robin Jones Kerr, a junior majoring in journalism, is a Hatchet opinions writer.