Putting items on a list just to check them off might feel good – but it doesn’t get you any closer to achieving a goal.

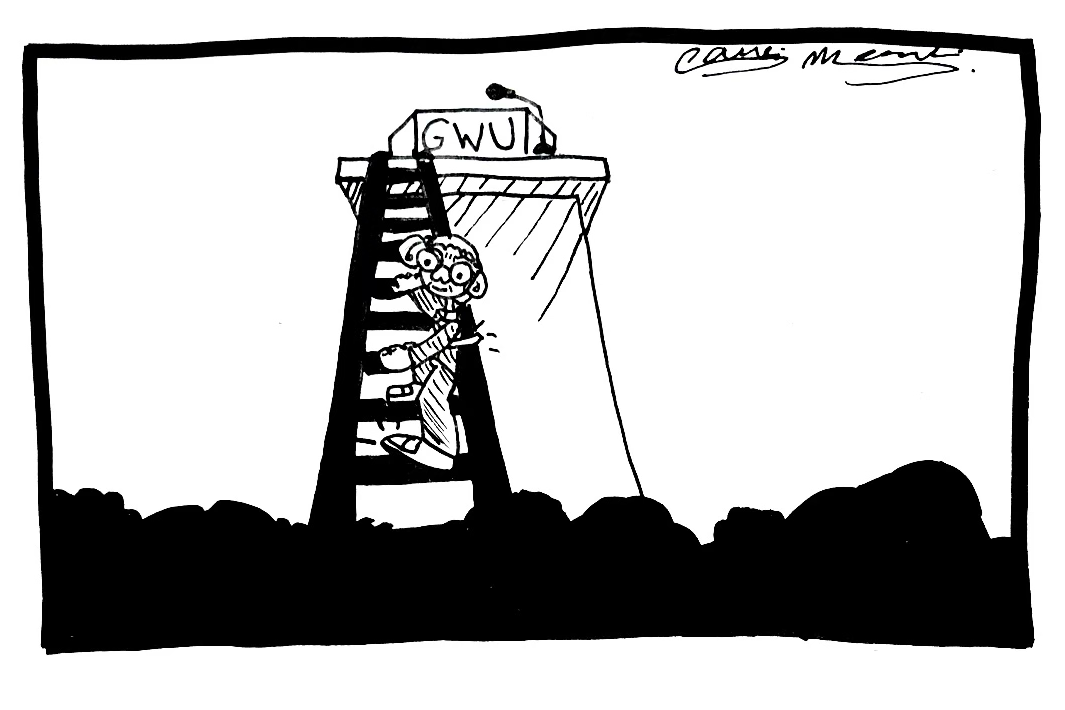

But unfortunately, that is the approach the administration appears to have taken with its study of the University’s workplace environment – giving itself a pat on the back and shirking real progress.

This month, GW released the results of a review which was led by one associate dean and one program director. Administrators decided to conduct the review following Penn State’s damning Freeh report, which pinpointed serious issues at the school following former football coach Jerry Sandusky’s acts of sexual violence.

To GW’s credit, it was one of the few schools in the nation that took a proactive step to ensure that cover-ups did not also occur here. And that’s admirable.

Thirty-five recommendations came out of the task force. So far, the new committee charged with working with administrators to improve University policies has begun work on 18 of them, like seeing whether GW should expand background checks for faculty and improve trustee training.

On the surface, this sounds like progress. But a closer look at the language shows that the recommendations were wrought with padded language and loopholes. Administrators might be able to check off boxes, but they won’t really get anything done.

Clearly there are problems to fix. The report may have claimed that GW has a “culture of openness and transparency,” but employees past and present disagree. One even called GW’s environment a “culture of repression.”

The claims against GW are adding up, rendering the report – which asserts that basically nothing is wrong – insignificant.

Even the proposed solutions are empty. Doug Shaw, an associate dean in the Elliott School of International Affairs and co-leader of the report, told The Hatchet it produced no “hard recommendations.” He also described the report as “a consulting project more than an investigative project.”

A consulting project tells administrators what they want to hear, without producing real critiques. An investigative project likely would create more sweeping change.

If there are deep-rooted problems with the administrators’ or staffers’ conduct, and if administrators were actually interested in identifying and remedying them, this report should have done more than outline a few superficial ideas that won’t translate into action.

To make this report worth everyone’s time, GW should have hired an outside firm. The results would likely have been more hard hitting if they were provided by a professional auditing group. An outside firm could have detailed a strict list of essential university improvements instead of a hollow set of guidelines.

After the Sandusky scandal, Penn State’s Freeh report offered dozens of substantive steps towards creating a culture of openness, which included hiring a university ethics officer, a chief compliance officer and expanding the general counsel’s staff. And though GW’s issues with dishonesty have not been as severe, it’s undoubtable that GW, like any institution, has more room to improve than GW lets on.

Take, for example, the task force’s recommendations on sexual assault. The administration has checked off the box next to the recommendation that reads “track the incidents of sexual harassment and sexual violence on campus at GW.” But institutions of higher education are already required to do this by federal law.

By putting their already-accomplished efforts on a list just to check them off, administrators falsely suggest they are making new progress on already-tread ground.

In the report, the administration also acknowledged that they will make an effort to monitor the traffic on Haven, GW’s online center for sexual harassment resources. But this seems obvious: Why would Haven have been set up if the University does not plan to invest resources in tracking its progress?

As students, we always want to see GW improve its workplace culture. And it seemed like this report, if genuine, could have been a perfect opportunity to do just that. But 14 months later, the outcome of a potentially powerful investigation lacked the substance to make a difference.