South Korea’s first and only astronaut spoke about her experience in space and the health challenges associated with space travel at a lecture on Tuesday.

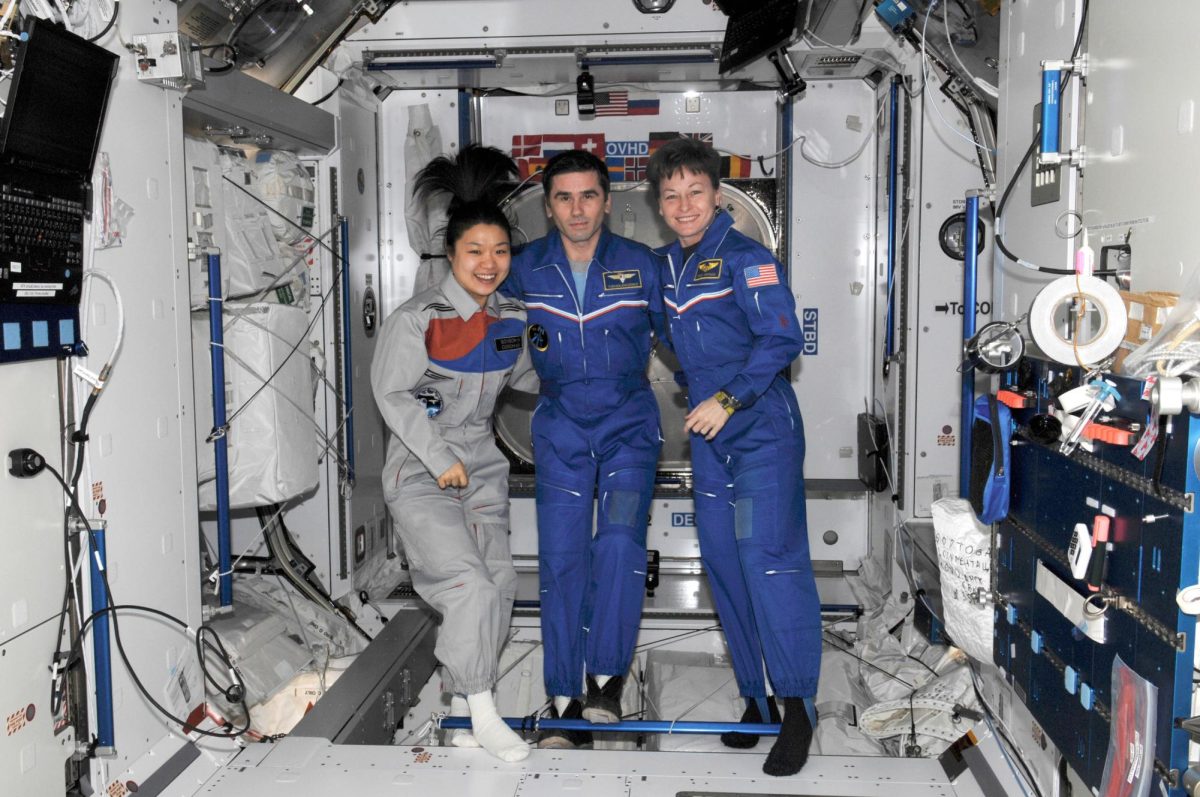

Soyeon Yi, who traveled to the International Space Station on an 11 day trip in 2008, discussed why she wanted to be an astronaut, the selection process for space travel and the medical challenges her and other astronauts faced while in space. Yi spoke to members of the GW community on a Zoom webinar hosted by the Office of International Medicine Programs.

Yi said when South Korea was taking applications for their first astronaut in 2006, she was in the final year of her biological systems doctorate program at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology and was planning on coming to the United States to serve in a postdoctoral position.

“My biggest headache was how I can be recognized by the U.S. professors as one of the Asian international students if I apply for a postdoctoral position,” Yi said. “And I realized that many of the Asian students had just the degrees and a perfect top score, but I didn’t have a perfect GPA, I didn’t have a top score.”

Yi said she realized many Americans were interested in science fiction shows and movies, like Star Wars and Star Trek, and thought that applying to be an astronaut would make her application more “eye-catching” to admissions officers. She said the best part of the training process was meeting people outside of those she knew from engineering school and forming close friendships with different people during the process.

“I think the biggest takeaway from the astronaut selection is opening my eyes to the real world because I was in a fake world in the engineering school and stuck in there,” Yi said.

While still working on her doctorate, Yi said she traveled to Russia — one of the five countries who manage the ISS — in order to participate in astronaut training and to learn the Russian language. She said during the day she would do space training and simulations and at night she would do data analysis and writing for her doctorate.

Yi said astronauts deal with many health challenges while in space, like motion sickness and trouble sleeping. She said she struggled with constant motion sickness during the first four to five days of her 11 day trip and kept a plastic bag in her pocket for whenever she needed to throw up.

She said all astronauts, including her, struggle with back pain in space due to zero gravity, which causes people to get taller. This occurs because the lack of gravity pushing down on the spine causes the vertebrae to expand.

“One interesting thing is your original height is a little bit taller than your height right now because of the gravity all your spines are pushed down. So all your discs are flexible, discs are pushed down. So when you go to the space, all that gravity is released,” Yi said.

Yi said she grew about an inch taller in space, which caused pain because her joints and muscles were stretched. She also said once astronauts return to Earth their heights return to normal within 10 minutes, which causes additional pain for two to three weeks.

Yi said another challenge she faced while at the ISS was difficulty staying asleep, as zero gravity causes constant involuntary movements that disturb sleep. She said when she had trouble falling asleep, she would open the window shade next to her sleeping bag and look down to Earth.

“I have a window right next to me, open the window, look down to the Earth, and it makes me calm and try to sleep again,” Yi Said.

Yi said when considering future space travel to further destinations like Mars, the biggest health care challenge is not physical health but mental health. She said if astronauts become depressed due to isolation, they endanger not only their own lives but the lives of their crew mates and the success of the mission.

“No matter how reliable the system you designed, one crazy person is enough to break everything, then destroy everything,” Yi said.

Yi said before considering long-term space travel, researchers need to study the physical and mental health effects of space travel, as the number of astronauts are few and not demographically diverse. She said there have been less than 600 astronauts in history, and of that number, less than 20 were women. Yi said the lack of diversity makes drawing conclusions about health effects hard for scientists, especially since there is so little data on female astronauts.

“The only solution is to make more females and more demographics, more diverse astronauts. Is the healthier for the future of humankind, for the human space flight,” Yi said.