Deep in the recesses of The Hatchet’s archives are the first writings of one of the United States’ most influential Hollywood scribes.

No, we didn’t get on the Nora Ephron train early, and Aaron Sorkin probably has never picked up a copy of the paper (his loss). But in 1932, L. Ron Hubbard, the founder and myth-like cult leader of the Church of Scientology, served as the paper’s associate editor during his two-year stint at GW.

There’s so many questions one can ask about Hubbard’s time at The Hatchet. He was, to put it kindly, an odd duck. After dropping out of GW after his second year in 1932 to embark on a voyage to Puerto Rico, Hubbard founded the Church of Scientology in 1954, a cultish dogma shrouded in suspicion due to its disciples’ bizarre practices and frequent mysterious unexplained deaths and disappearances of internal dissenters.

Scientology’s beliefs, in theory, are all about immortality and individual destiny, that everyone can live forever if they only seek to fulfill their potential. Hubbard claimed that all humans were simply a conglomeration of spirits that the Galactic Federation ruler Xenu had banished to Earth and sealed in ice tens of millions of years ago — a dogma so logical it’s shocking the church doesn’t have wider reach.

I couldn’t help but wonder: Even though his cult is mostly based on the science fiction he wrote after being at GW, are there early traces of Scientology in his war-centric creative writings?

Lucky for this bizarre rabbit hole I decided to send myself down, the Scientologists have me covered. Galaxy Press, Hubbard’s publisher, keeps a full list of the late “Battlefield Earth” author’s work, including four pieces he wrote for what was then the “University Hatchet,” largely inspired by trips he took to China in 1928 where he became enchanted with the seafaring life and all preserved in The Hatchet’s online archive.

Hubbard’s first work for The Hatchet — and per Galaxy Press, his first published work overall — was called “Tah,” a tale written in February 1932 following a 12-year-old Chinese foot soldier named Tah whose body slowly degrades on a march that leads him to his death in battle.

“Tah” is, to be blunt, almost unreadably racist. Hubbard writes the dialogue between Tah and other characters in broken English. Outside of the plain-to-see prejudice dripping from Hubbard’s words, the choice doesn’t make much sense in the logic of the piece — why would a bunch of people in China who don’t normally speak English be speaking English to each other? If they were speaking in another language, why write their dialogue in a style of language typical of so many horrible stereotypes? It’s almost as if the founder of the strange scandal-filled cult of Scientology was, in fact, not a particularly progressive, socially conscious fellow. Who would’ve guessed.

“Grounded,” an April 1932 piece, follows Ensign Reynolds, a soldier aboard a boat in China who meets his new commander Lieutenant Hampden. Except Reynolds was already well-familiarized with Hampden — the lieutenant had previously been a pilot until a plane he was in crashed. He parachuted out with plenty of time to spare, but his flying partner wasn’t so lucky, leading to accusations that Hampden masterminded the murder of his co-pilot.

Suspicion begins to swirl around Hampden on the boat. Reynolds, too, finds Hampden’s behavior odd at times, like when the lieutenant hides below in a cabin as a gunfight breaks out between the crew and an unknown enemy on the ship’s deck, or when he seemingly pays no mind to a headless body that floats by the boat (the body is never explained further — I guess Hubbard had too many midterms to fully proofread his B plots).

But it’s during that gunfight, after the lieutenant finally makes his way to the bridge, when Hampden redeems himself. He leads his crew through the battle, and after he’s hit badly he declines medical attention, saying that the doctor should go help his crew instead. The story closes on an ambiguous note, with the dying Hampden wishing to his wife and late co-pilot that the world may now finally know “the truth” — which Hubbard never reveals.

I’ll confess that I, at first, thought “Grounded” was a harmless, fun enough pulp — that is, until the eerie connection between Hampden’s demise and the mysteries of Scientology set in. Key figures in the Church of Scientology disappeared with a similar veneer of suspicion and hand-waving explanations for decades, like current leader David Miscavige’s wife Shelly, who hasn’t been publicly seen since 2007. I’m not going to purport that “Grounded” is the cause of that part of the cult’s ideology, but the resemblances are striking.

“The God Smiles,” a play from that same year, follows two Russian pro-Communist dissidents trying to escape China. The play was seemingly a hit at the time — it won a GW one-act play contest in 1932. Except, there might be just a little reason to doubt the validity of that award: The contest was sponsored by The Hatchet’s literary review, where, if you’ll remember, Hubbard called some of the shots.

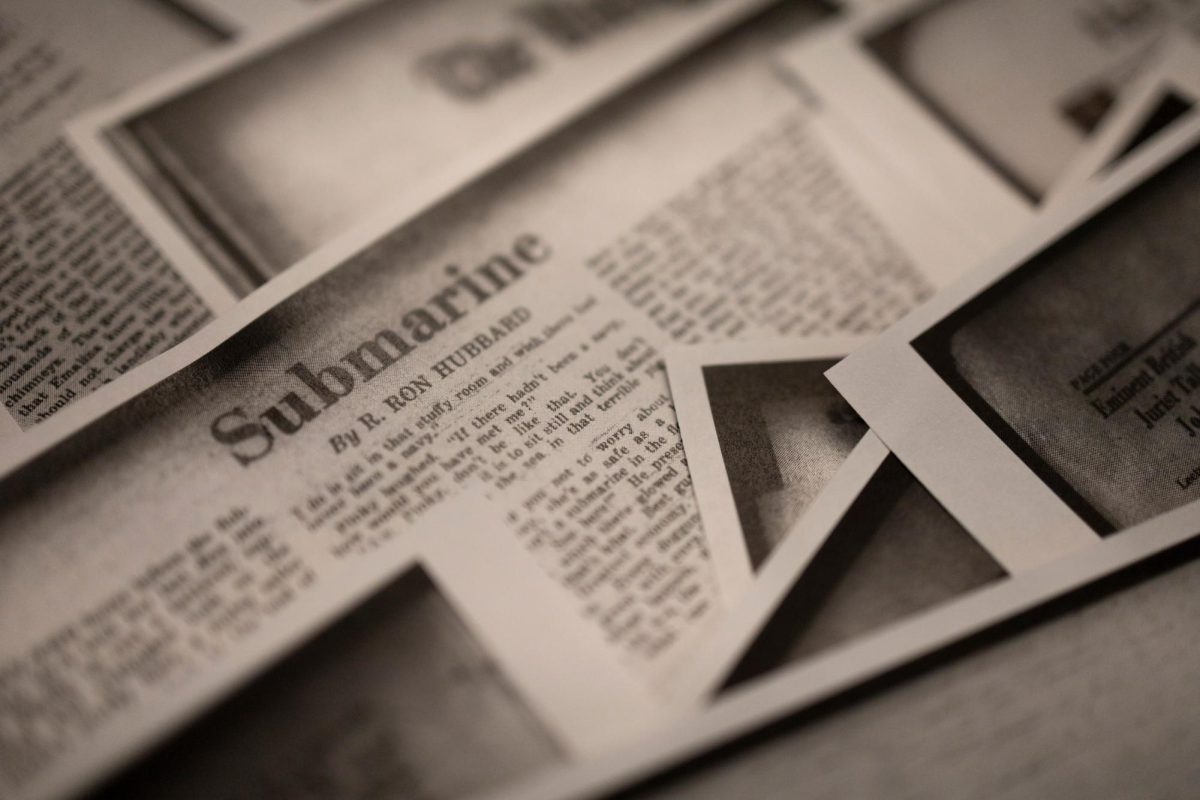

Hubbard’s final piece for The Hatchet came later in November 1932, entitled “Submarine.” It follows Pinky, a naval submarine officer on a 72-hour leave in San Diego, California, with his paramour Madge. The story is, in a word, boring.

“Submarine” doesn’t have any of the classical pulpy appeal of “Grounded,” instead just tracking a couple arguments Madge and Pinky have about his dangerous work and a prolonged series of mishaps that potentially imperil his ability to return to his submarine before it sets off. A couple of the lines of 1930s swinging dance dialogue gave me a chuckle — Pinky tells Madge they’ll go “Paint the town red, kid biscuit” — but the driving drama of whether Pinky will get on the submarine in time lacks any sort of compelling narrative force.

The more intriguing nautical drama of Hubbard’s 1932 came from his own journey on the high seas during that summer. The “pilot and adventurer,” as a Lansing State Journal article from the time described Hubbard, set out with some fellow GW students and other budding academics from around the country to tour the Caribbean. They wanted to make pirate movies and shoot film of the area’s flora and fauna, a blend of Frank Capra and Charles Darwin.

Hubbard said after that the trip resulted in “a wonderful summer.” His publisher claims that he and his fellow expeditioners returned with “numerous” scientific samples.

But everyone else agrees the journey was a disaster. The crew ran out of money, barely shot any film, hemorrhaged members the entire time and, in the words of veteran seaman F.E. Garfield, who was aboard the ship, had “the worst and most unpleasant” voyage. Hubbard’s crew even made an effigy of him and hanged it.

While we don’t know for certain why Hubbard chose to drop out and hop on a new boat to Puerto Rico rather than returning to school, it’s not a huge leap to say it might’ve had something to do with his relative lack of popularity at GW. “Submarine” closes on Madge bidding Pinky farewell, telling him “I’ll be waiting Pinky. Right here, when your boat comes in.” It’s fair to assume there wasn’t a single GW student waiting, right there, for Hubbard’s ship to return to Foggy Bottom.