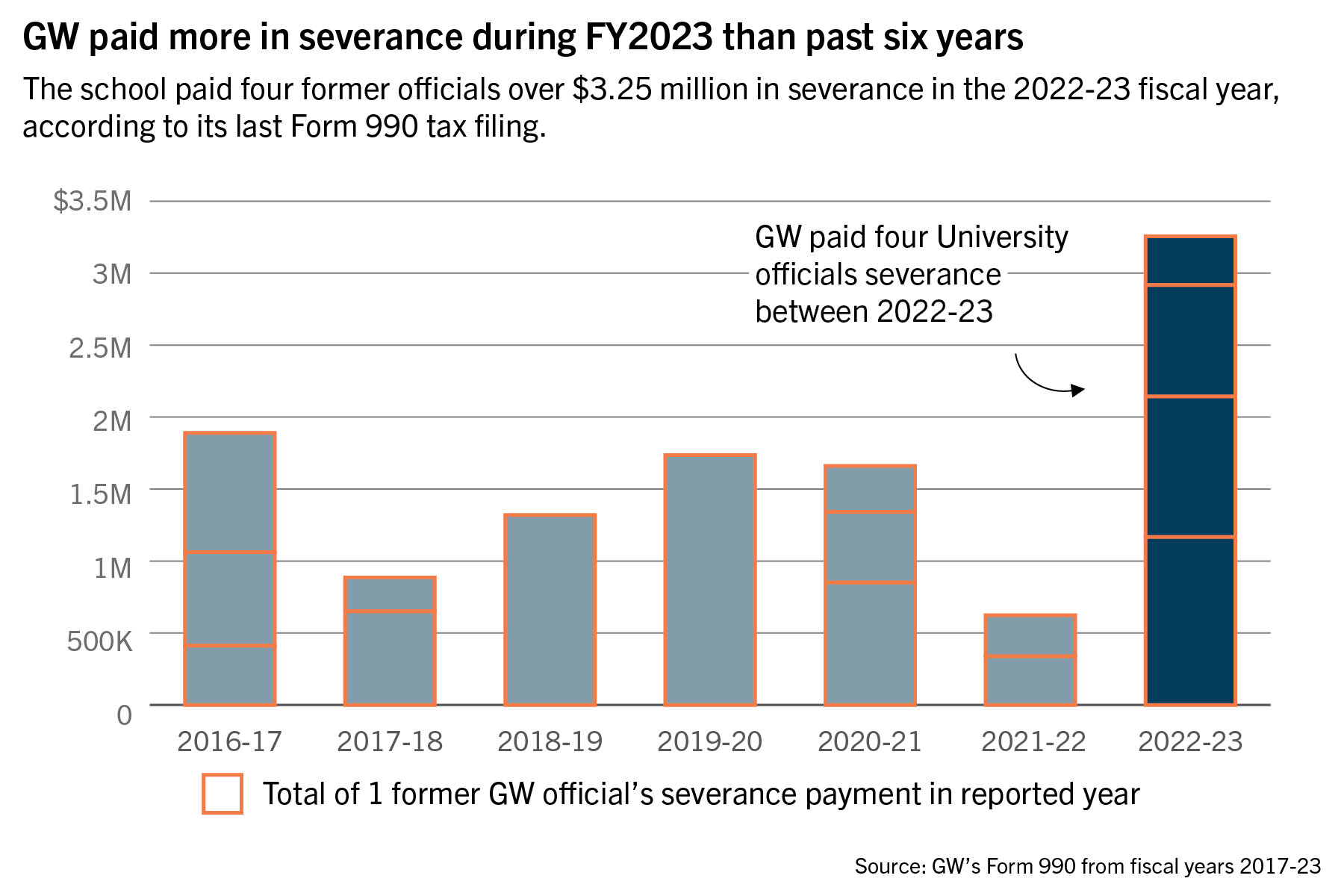

Faculty senators said the over $3 million in severance that the University paid four former officials between 2022 and 2023 may have been used as a tool to help administrators carry out departures.

Annual financial disclosure forms from fiscal year 2023 show that former University President Thomas LeBlanc received $1,167,000 in severance since he retired from the University in 2021 and former Chief Financial Officer Mark Diaz has received $976,440 since leaving in 2022. A University spokesperson declined to say if the officials left on their own volition or involuntarily, and members of the Faculty Senate suspect the administration may have used the severance payments to usher them out of their positions.

By the time of their departures, both former top officials were considered deeply unpopular among faculty, staff and students. LeBlanc’s four-year term culminated with widespread calls for his resignation from faculty members who felt his leadership did not match the University’s core values. Diaz and LeBlanc came under fire by faculty in January 2020 over the 20/30 plan, with some faculty senators saying the move would force GW to take on more debt to account for lost revenue.

Jennifer Brinkerhoff, a faculty senator and professor of international affairs, said decisions about severance payments were made by the University before she was a senator, but some of the severance paid to Diaz could be the result of GW trying to replace LeBlanc’s administration.

“These buyouts can become very large if the ‘separation’ of that person from the university is a high priority, they already command a large salary, and they know they are in a strong bargaining position,” Brinkerhoff said in an email.

She said it is common in the “business world” to use severance as a way for a new leader to phase out the old administration and replace it with their own people.

Diaz was hired by LeBlanc in August 2018 after the two worked together at the University of Miami and left shortly after the former University president. LeBlanc stepped down in January 2022 after announcing months earlier that he planned to leave in at the end of the academic year and told trustees he was “flexible” about his end date and would be open to leaving earlier if desired.

Officials announced LeBlanc’s departure as a retirement and maintained that Diaz chose to depart on his own accord, never specifying where he would work after GW.

Severance pay provisions are common across higher education, with 60 percent of respondents to a 2014-15 survey of four-year college and university presidents reporting they had severance agreements in place with their leaders, according to Inside Higher Ed. GW does not list a severance policy on their Human Resource Management & Development website.

A University spokesperson declined to explain GW’s policy for granting severance payments to employees who leave on their own accord. They also declined to comment on how officials determined severance payments for LeBlanc, Diaz or former General Counsel Beth Nolan — who retired from the University in June 2021 — who determines severance recipients, payment frequency and the method used to calculate allocations.

The spokesperson deferred comment on LeBlanc and Diaz’s severance payments to a previous statement on the University’s Form 990 filing in August, which states that “compensation for senior administrators is determined by a multitude of factors, including the prevailing market rate, experience and the qualifications that an employee brings to the job.”

Philip Wirtz, a faculty senator and professor of decision sciences and of psychological and brain sciences, said he wonders if money that could have been used for faculty, staff and student needs was instead allocated to severance payments last year.

He said he has to ask “where is the money coming from” to support these expenses, including the “eye-popping” salaries that recently appointed administrative hires have received like Provost Chris Bracey, who received a $391,811 pay bump in the 2022-2023 tax cycle to earn $966,960.

He also pointed to the more than $80 million dollar deficits run by the Medical Faculty Associates each year — a nonprofit group of doctors, nurses and health care staff controlled by GW who owe the University $200 million after several years of financial shortfalls.

“I have to wonder if the answer to that question is ‘from funds which would otherwise go to supporting GW’s academic initiatives — very much including student financial aid,’” Wirtz said in an email.

Wirtz said the University needs to be able to “fully financially support” the needs of its students and its academic initiatives before issuing large severance payments to its administration.

“If, instead, we are paying millions of dollars in ‘severance’ to former executives, it would make me wonder if GW has its priorities straight,” Wirtz said.

Former Head Basketball Coach Jamion Christian, who officials fired in 2022 after a poor season by GW’s basketball team, received $774,000 in severance pay during FY 2022-23. Nolan received $338,000.

GW has offered severance to 14 former employees between FY 2017 and FY 2023, according to the University’s publicly available tax forms. Former Chief Financial Officer Lou Katz received the highest payment out of the payments reported during the six pay cycles — $1,736,534 in severance in FY 2020 upon his retirement after 28 years at GW.

Other notable payments include $1.32 million in FY 2019 to former Athletic Director Patrick Nero, who resigned in 2017.

Brinkerhoff pointed to severance payments to past faculty members that she theorized officials used to drive personnel turnover, including a buyout in the School of Business in 2014, where GW offered six-figure sums to business school professors who had taught at the school since 1990 in an effort to boost GW’s profile with younger, more research-minded professors.

“Even faculty members are on occasion offered buyouts to agree to retire or move on,” Brinkerhoff said. “The Business School did this in 2014 publicly and at scale. Sometimes buyouts, faculty or otherwise, are negotiated on a case-by-case basis and so don’t make the news.”

GW also paid former professor of biochemistry Rakesh Kumar $650,000 in severance pay and a buyout of tenure between in FY 2018, after receiving $828,150 in severance the year before, per GW’s financial documents.

Kumar resigned in 2016 following an $8 million lawsuit against GW for removing him from his position as chair of the biochemistry and molecular medicine department without following protocol, which was settled in August 2016.

Steven Levine — a lecturer at the Boston University School of Law and senior partner at Brown Rudnick, an international law firm — said the severance payments could have been stipulated by the former administrators’ contracts in the event of departures. He said contracts often include a provision that allows officials to receive severance regardless of their reason for leaving, unless they are fired for cause.

Levine said offering severance can also be used by universities and their trustees, who oversee top administrators’ paychecks, to entice someone to leave their position when they haven’t done something illegal or immoral that merits their firing.

“While that may be ambiguous, if the trustees decided that it was in the best interest of the institution for this guy to leave, they have to make some type of arrangement to induce him to do that and that would be true to the CFO and the president,” Levine said.