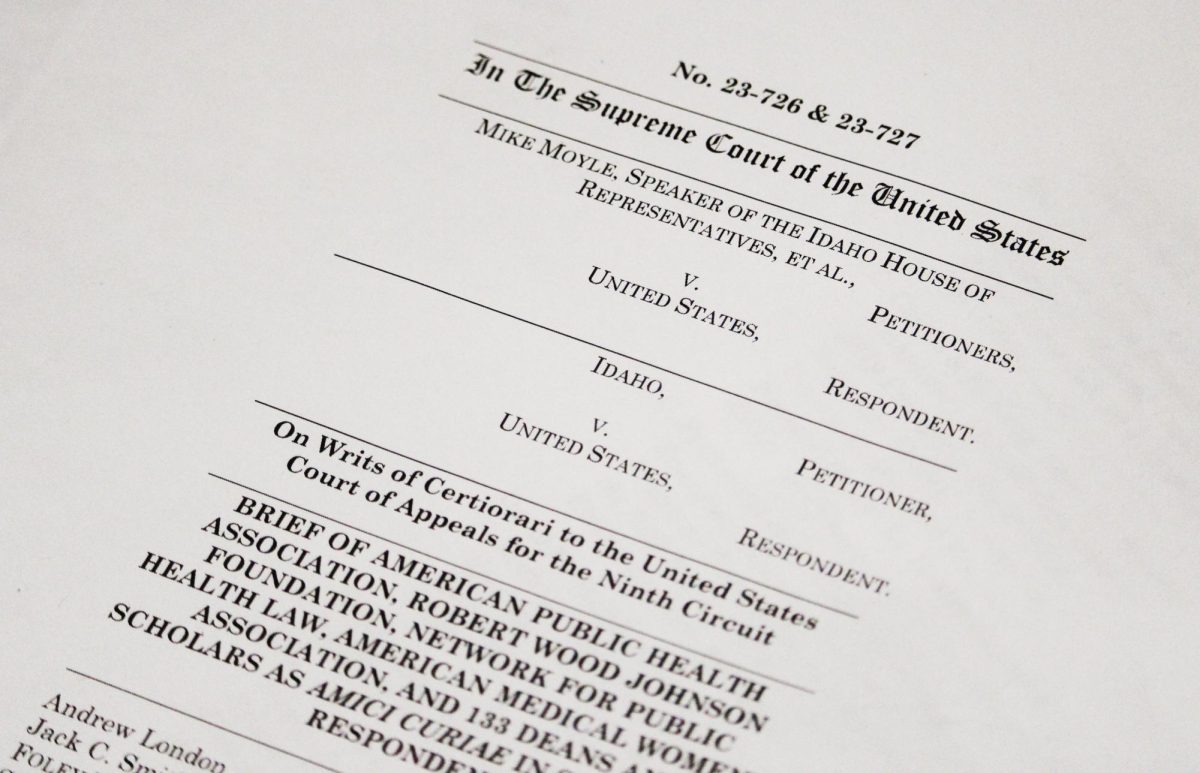

More than 40 faculty members signed an amicus curiae brief last month urging the Supreme Court of the United States to protect emergency abortions in a case that the high bench will hear Wednesday.

In Idaho v. the United States, the Supreme Court will rule on whether the Emergency Medical Transport and Labor Act of 1986, which prohibits hospitals that receive Medicaid funding from refusing emergency medical care for patients, preempts or supersedes an Idaho state law that restricts abortions. Faculty members said they signed the brief because if the court rules in favor of Idaho, states would be able to criminalize emergency medical care that results in abortions.

Latin for “friend of the court,” amicus briefs refer to briefs of legally and materially relevant information to an upcoming case, most prominently those heard by the Supreme Court. Sara Rosenbaum — a founder of the Milken Institute School of Public Health Amicus Brief Project, which has sponsored close to a dozen amicus briefs to courts in the last 15 years, and the founding chair of the Department of Health Policy at Milken — said these briefs play a crucial role in Supreme Court cases where the case’s plaintiff and respondent must adhere to the Court’s strict page limits in hearings.

EMTALA authorizes emergency department doctors to independently evaluate whether patients require an abortion to avoid death or a lasting health injury as part of stabilizing treatment. But Idaho’s Defense of Life Act, which went into effect in 2022, prevents a physician from terminating a pregnancy, only unless doing so is necessary to save the mother’s life.

Rosenbaum said if the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Idaho, it would set a precedent to shift the regulation of emergency abortions away from the federal government to the states. She said such a shift would open the door to criminalization of doctors who perform emergency abortions.

“Doctors are fearful of doing anything now because if they comply with EMTALA, then the state could arrest them and prosecute them and imprison them for violating state law,” Rosenbaum said. “That’s the problem and the state of Idaho law directly conflicts. It’s called direct conflict preemption.”

Rosenbaum said EMTALA expressly prohibits denial of screening and stabilization on any basis like insurance status, income, pre-existing conditions and citizenship.

Rosenbaum said the Justice Department filed the suit to resolve the conflict between federal law and Idaho state law, arguing that Idaho’s law is unenforceable. She argued EMTALA, a federal law, preempts or supersedes Idaho law in requiring that physicians must provide stabilizing medical care that results in an abortion in both cases that would save the mother’s life and in cases to prevent lasting health injury.

“So what EMTALA says is, if you’re pregnant, and you have a medical emergency, you have a right to stabilizing treatment just like anybody else,” Rosenbaum said. “And what is involved in that stabilizing treatment, is what a doctor says is the stabilizing treatment.”

She said the brief argues that enforcing EMTALA would not reverse the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, which ruled that the Constitution does not grant the right to an abortion.

“Everybody has been very careful to argue this is an extremely narrow case,” Rosenbaum said. “Nobody is attempting to argue that EMTALA overturns Dobbs. It is an exception to Dobbs.”

Lynn Goldman, the dean of the Milken Institute School of Public Health, said she signed the brief because she was “appalled” that Idaho was attempting to weaken protections for patients protected under EMTALA.

“The state of Idaho, in its challenge to this guidance, is threatening to deny women life-saving treatment,” Goldman said in an email.

Goldman said the implications of the Supreme Court’s decision will not only impact women’s health but could allow hospitals to turn away other kinds of emergency treatment if the Court rules in favor of Idaho.

“If the Supreme Court rules in favor of Idaho, the impact could go far beyond women’s healthcare,” Goldman said. “It could allow states to ban treatment for disfavored emergency conditions such as treatment for HIV or complications of gender-affirming care.”

Peter Shin, an associate professor of health policy and management who signed the brief, said EMTALA applies to all hospitals receiving federal funding through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which provides government health insurance. CMS disburses federal funds to state programs for Medicare, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Shin said serious EMTALA violations may lead to the stoppage of federal funds from CMS to noncompliant hospitals, which would likely place them in a budget deficit. This gives hospitals a strong reason to comply with EMTALA, Shin said.

“CMS can always pull the Medicare funding if the violation is really severe and in many cases, when CMS pulls that funding, or that payment, the hospitals will go under,” Shin said. “So they have, hospitals have, real incentive to comply with the federal law.”

Leighton Ku, a professor of health policy and management and the director of Milken’s Center for Health Policy Research who signed the brief, said the Idaho case serves as one example of an ongoing national reproductive rights debate. Ku said when Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg died, pro-life advocacy groups thought the court had become conservative enough that they could chip away at the federal abortion protections that prior rulings granted.

“This has been an extremely volatile issue that people care deeply about on both sides, and in a way, feel free in saying more than just both sides, there are many potential sides to this,” Ku said.

Diana Mason, a registered nurse and a senior policy service professor for the Center for Health Policy and Media Engagement in the School of Nursing who signed the brief, said in states with abortion bans, both clinicians and hospital administration regularly delay emergency care to pregnant women that may result in abortions out of fear of criminal prosecution. She said such delays increase the risk of death or severe injury that can prevent a woman from becoming pregnant again.

“This is a woman who you could be jeopardizing,” Mason said. “If you don’t intervene early, you could be jeopardizing that woman’s ability to have another pregnancy or just to live.”