Editor’s note: This article contains references to sexual violence and suicide. If you have faced sexual or dating violence on or off campus, call GW’s Sexual Assault & Intimate Violence (SAIV) Helpline at (202) 994-7222. If you or someone you know has experienced suicidal ideation, call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or reach the Student Health Center at (202) 994-5300 and ask to speak to a counselor.

On Sept. 22, I recruited interested students to The Hatchet at a University Yard org fair and then attended a recruitment event for Beta Theta Pi, looking ahead to my final year of college. Later that night, I would be sexually assaulted.

For the past five months, I’ve remained silent about my assault. I’ve hid it from family, friends, officials and even members of this newspaper, but this silence hasn’t been wholly voluntary.

Survivors of sexual assault are often afraid to come forward about their experiences. The stigma surrounding sexual assault emboldens derisive reactions against survivors, leading to further violence and trauma.

Throughout my time at GW, social media accounts like GW Survivors, GW Protects Rapists and Abolish Greek Life GW have detailed anonymous stories of sexual and dating violence on GW’s campus. These pages came and went, leaving heart-wrenching stories that remained nameless, faceless and helpless.

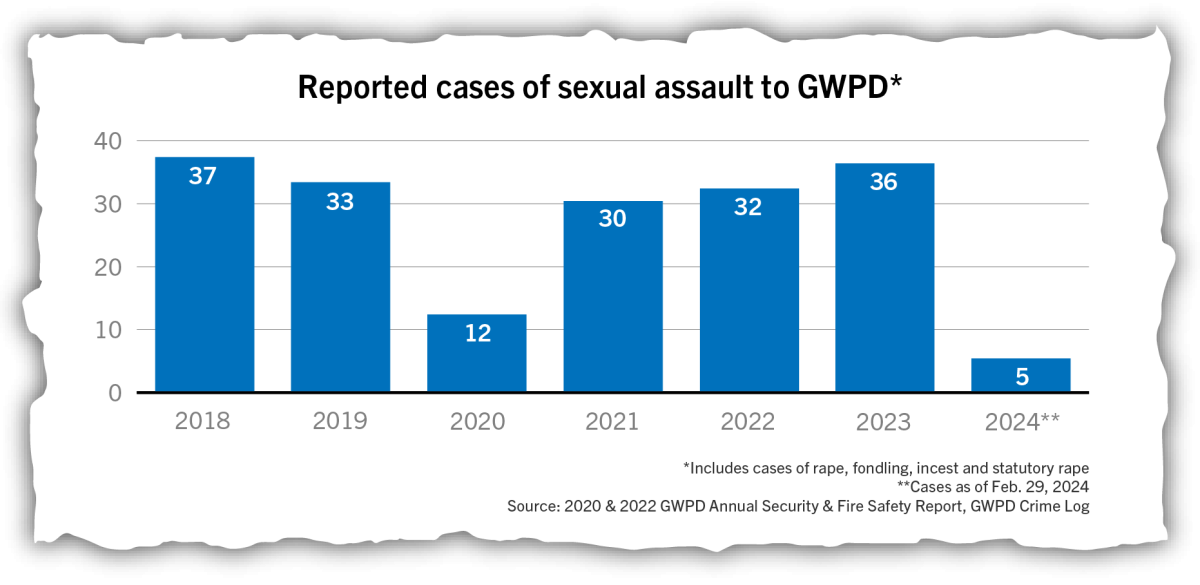

The GW Police Department continues to publish cases of sexual and dating violence every month, identifying case numbers, locations and incidence times. However, entries in the crime log can only say so much, unable to tell the full stories of those who painfully reported.

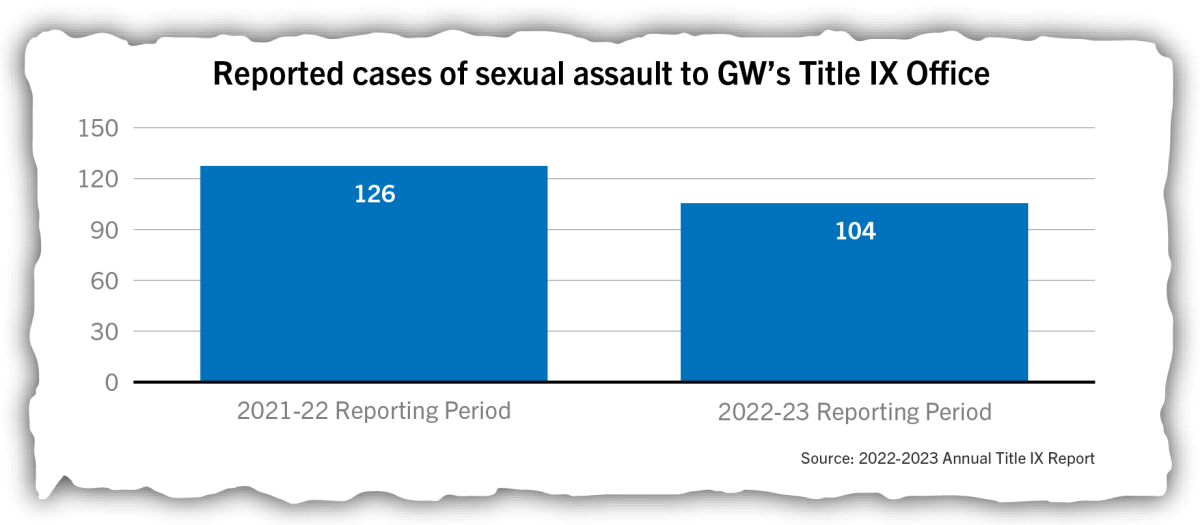

There were more than 200 reports of sexual and dating violence filed with GW’s Title IX Office over the past two academic years. That’s more than 200 people who have each had to survive the unbearable, often with those around them unaware of the pain they’ve faced or will continue to face. The real number is likely larger.

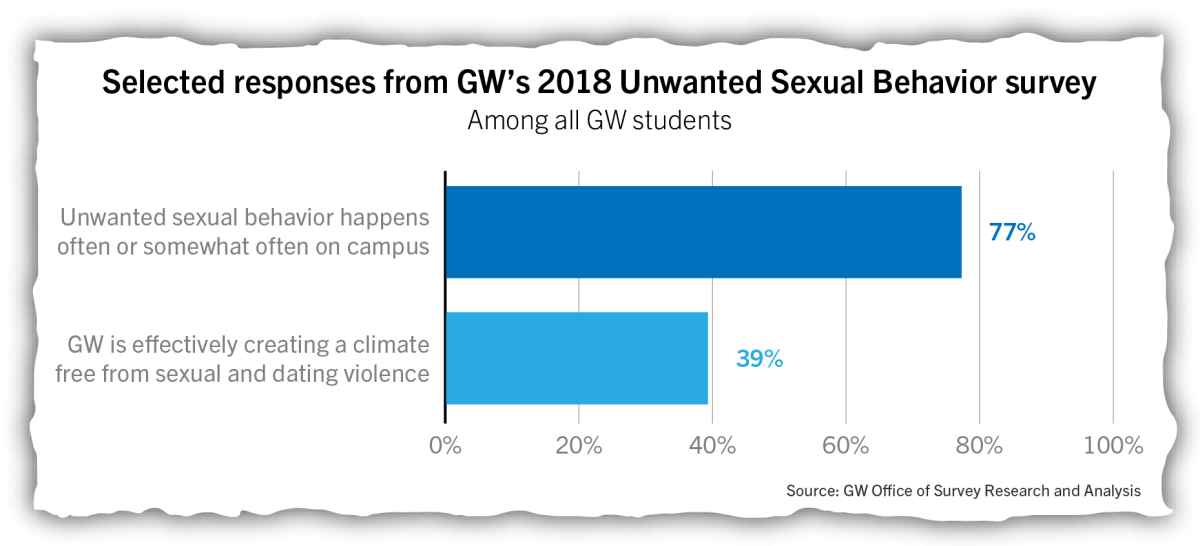

In response to a growing awareness of sexual violence on college campuses across the country in the 2010s, GW conducted “climate surveys” to measure students’ experiences with unwanted sexual behavior on campus starting in 2014.

Nearly one-fifth of undergraduate students said they had personally experienced sexual and dating violence while at GW in a 2014 survey. However, only one-tenth of undergraduate students reported improper behavior to an authority figure, and those who did report their experiences were more likely to find GW’s response inadequate (35 percent) than adequate (17 percent).

In 2018, nearly four out of five GW students believed that sexual and dating violence was happening either often or somewhat often on campus, but only 39 percent felt University officials were doing enough to provide a campus free of sexual and dating violence.

Since then, the climate surveys and other sexual assault prevention efforts on campus have gradually faded from the GW community’s collective consciousness as nationwide calls against sexual violence became muted after the height of the #MeToo movement.

But in the last four years, students have been confronted with the prevalence of sexual violence on campus and witnessed prominent student leaders be accused of sexual misconduct.

Students continue to whisper stories of drink spiking, domestic violence and sexual assault that go unrecognized and unresolved. As a result, the University community is largely unaware of the experiences of survivors and the effects trauma can have on one’s daily life. Instead, due to stigma and misguided ideas on recovery, survivors are expected to dwell on their trauma and isolate themselves from the rest of society, losing out on education, professional opportunities and socialization.

Survivors are called such not simply because of the individual experiences we’ve faced but because of our fight to survive in the aftermath of what we’ve faced.

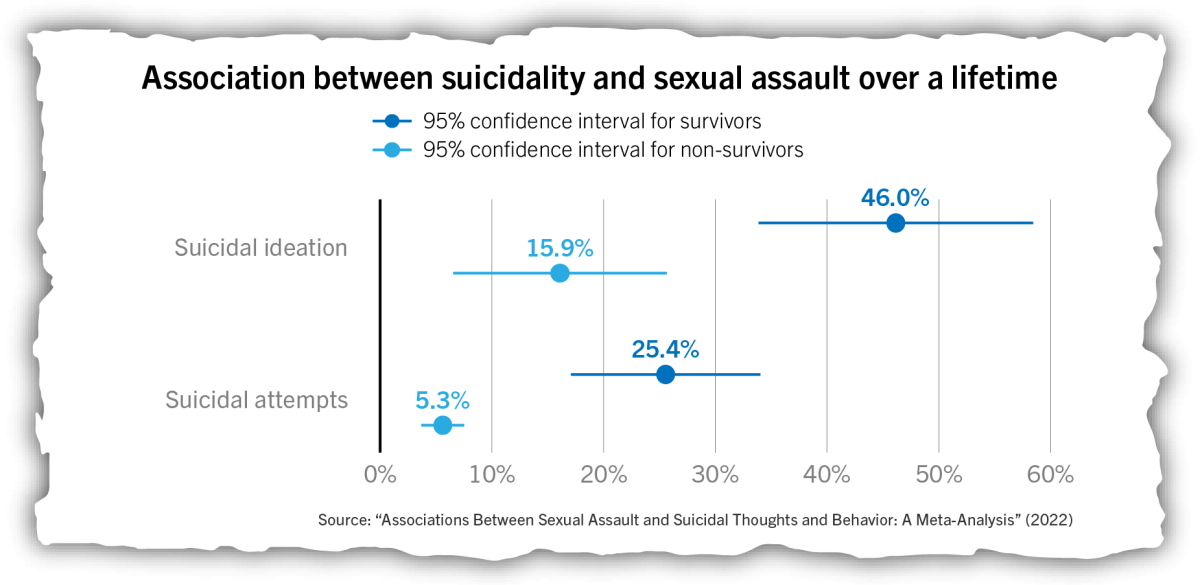

Survivors of sexual assault are three times more likely to experience suicidal ideation and five times more likely to attempt suicide than those who haven’t throughout their lifetime.

Surviving is difficult when your productivity is stifled, your safety is put into question, your trust is broken and your motivation is eradicated, especially while those around you are unaware and are often more willing to make assumptions and judgments, putting your utility over your humanity, rather than to inquire how you are.

But how can we solve this problem on campus if we can’t fully see it? How many more reports must be made before we can finally acknowledge it? And how long do we have to wait before survivors can be free from silence?

Following my assault, I knew that I wanted to report at some point later on, saving evidence under my bed and undergoing a forensic exam. But I was reminded of past cases where survivors were either mistreated or punished by authorities, and I was discouraged from coming forward.

In the months following, staying silent provided me temporary comfort, but it also made me believe that what happened to me wasn’t wrong enough. And if I can’t report mine, how can I wait for other survivors to come forward about theirs?

And so, I reported it.

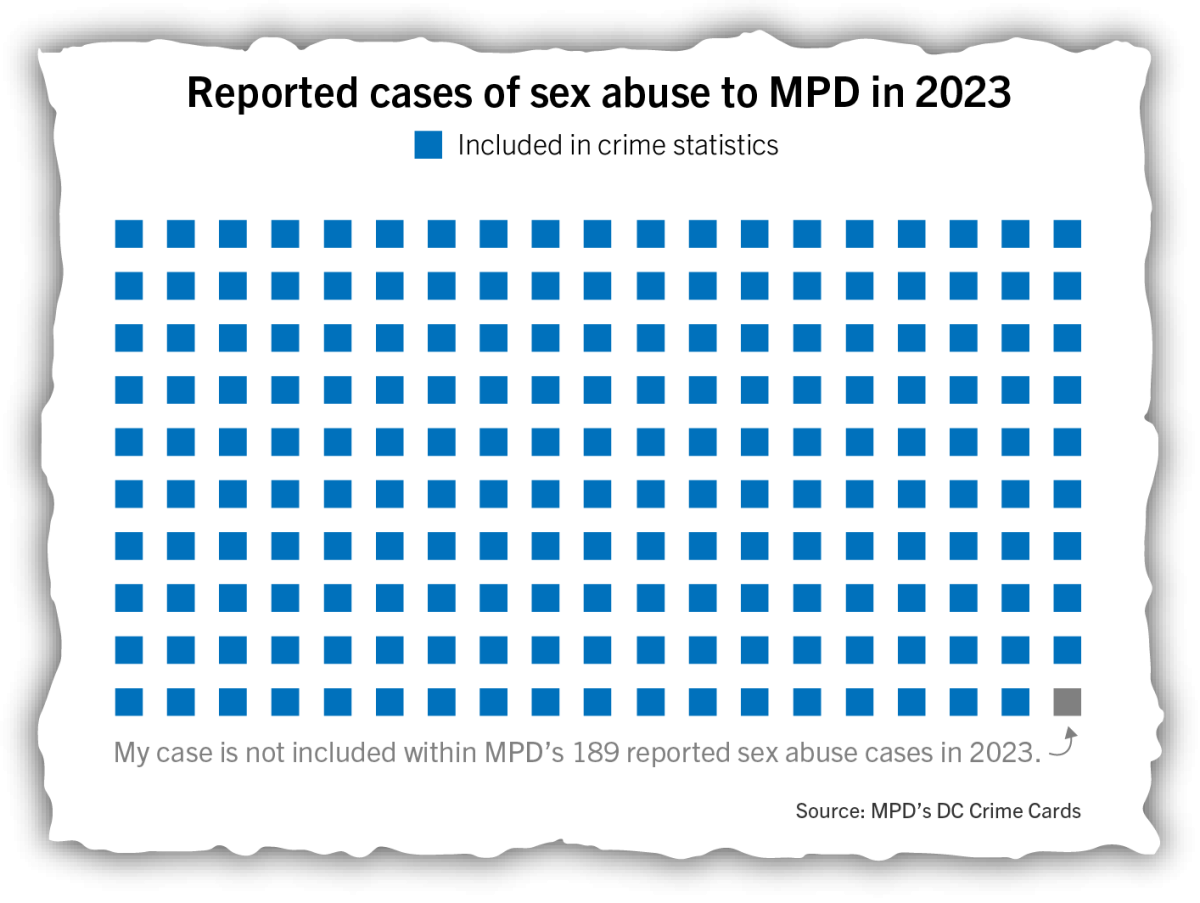

I reported my assault to the Metropolitan Police Department on Dec. 16. However, as of the writing of this piece, I cannot be found within MPD’s crime statistics. I am hidden from the public’s awareness, and other survivors may be hidden, too. So, I also reported my assault to GWPD in January and the Title IX Office in February, joining the other nameless entries in the crime log.

I decided to report because I believed what happened to me was wrong and because I refused to give in to the pressure that silences survivors from coming forward. Though I recognize survivors have no obligation to publicly discuss their assaults, I find it my personal responsibility to be open about mine.

The silence that survivors are expected to assume has hindered any substantial attempts to mitigate sexual and dating violence on college campuses and in greater society. When survivors can’t discuss their experiences openly, evidence of systemic failures goes unmentioned.

Furthermore, sexual and dating violence awareness should not be relegated to prevention trainings and consent workshops. Awareness should extend to educating the public on the effects sexual and dating violence can have on society and promoting greater empathy for survivors.

The first step in fighting against sexual and dating violence is quashing the stigma that inhibits its progress. We must have open conversations to develop solutions that both protect and support our community.

When survivors suffer in silence, society suffers in silence.

Nicholas Anastácio, a senior receiving double degrees in political communication and data science, is The Hatchet’s community relations director.