In 1941, Rosemary Kennedy, the sister of future President John F. Kennedy, was taken to GW Hospital.

The 23-year-old had dealt with an array of mental and physical health struggles throughout her life, including intense mood swings, seizures, irritability and depression. Her father, Joseph Kennedy, authorized a procedure considered at the cutting edge of psychiatry, a possible cure for even the most hopeless cases: the prefrontal lobotomy.

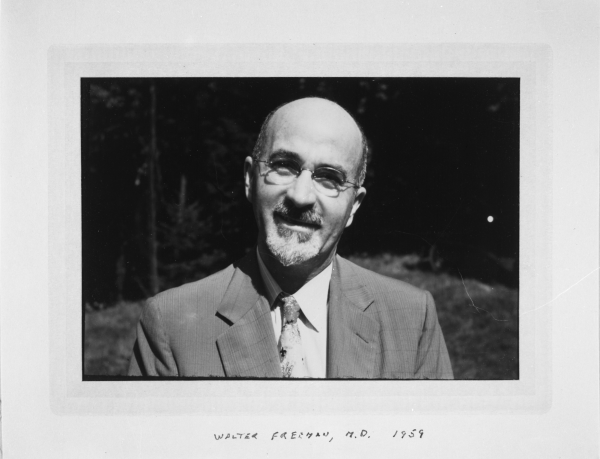

Joseph put his trust in psychiatrist Walter Freeman, the first chairman of the neurology department in the School of Medicine at GW, who pioneered the lobotomy, a brain surgery in which doctors sever neural pathways in individuals with mental disorders. Despite pleads from Rosemary’s siblings not to pursue the procedure, Joseph approved the surgery, which Freeman performed with neurosurgery department head James Watts, without telling his wife, Rosemary’s siblings and, allegedly, even Rosemary herself.

At the time, laws allowed fathers and husbands to make medical decisions for women. It would be decades until the law allowed women increased autonomy.

Freeman likely ordered medical staff to shave Rosemary’s head upon her arrival for the procedure, according to research presented in Kate Clifford Larson’s book “Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter.” Staff strapped patients’ feet to operating tables, shaved the top of their heads and masked their line of sight with towels and drapes while performing “unnamed tortures,” Larson wrote.

Andrew Scull, a research professor of sociology at the University of California, San Diego, said Freeman and Watts “very unsuccessfully” operated on Rosemary.

“She was rendered incompetent and barely able to walk and talk,” Scull said. “She lived for many decades but in a very badly damaged state.”

Freeman described the aftermath of lobotomies as “surgically induced childhood” and argued it was a “necessary stage in the patient’s recovery,” according to “The Lobotomy Letters: The Making of American Psychosurgery” by Mical Raz, a professor of history and clinical medicine at the University of Rochester. She wrote that through letter correspondence and professional settings, Freeman would reassure concerned family members of lobotomy patients who became “uncooperative” and “childish” following the procedure by saying their behavior was a temporary stage that preceded their recovered personality.

But Rosemary never reached that point. She was institutionalized at St. Coletta, a care institution for people with disabilities in Jefferson, Wisconsin, away from the rest of her immediate family after 1941 until she died in 2005 at age 86.

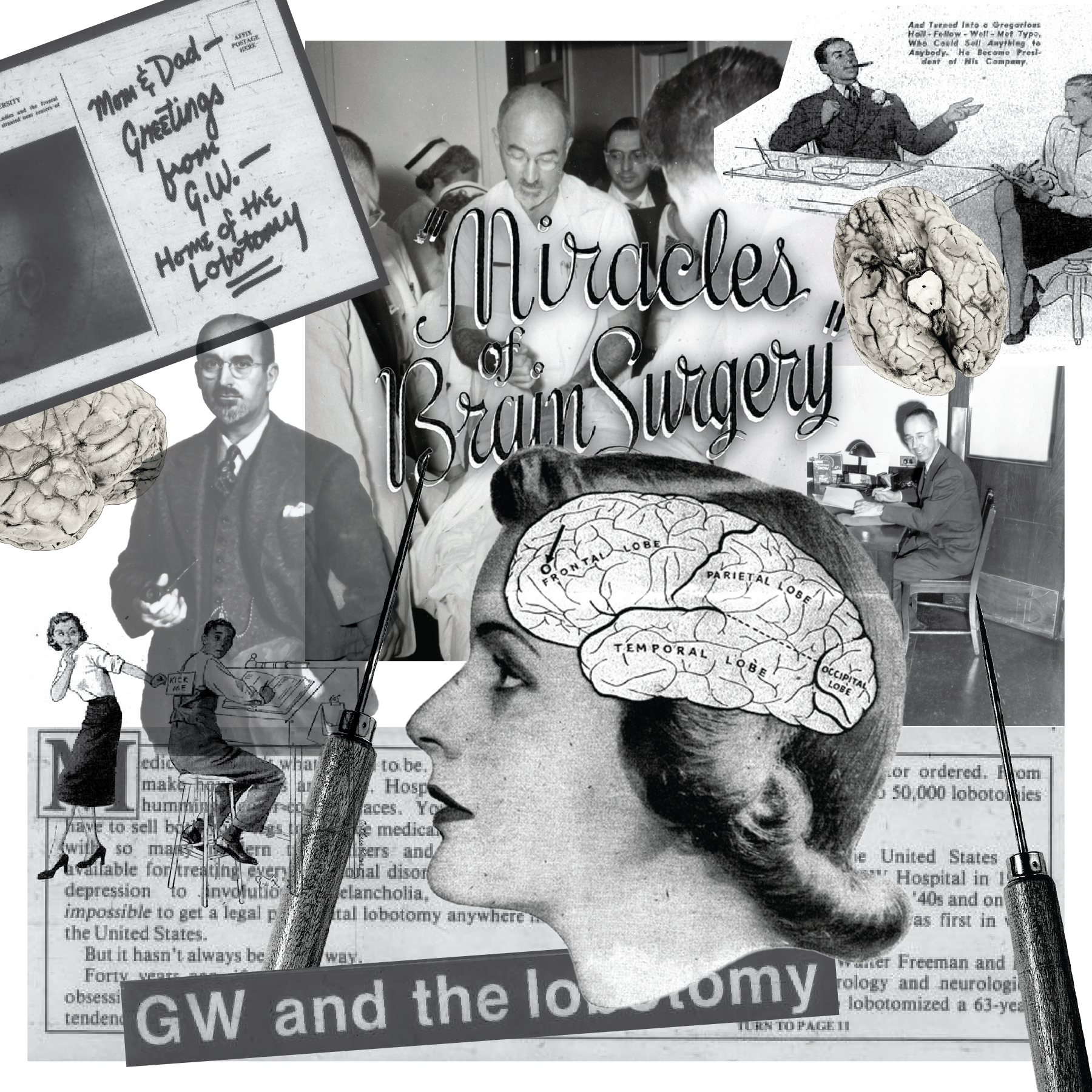

Rosemary’s case is perhaps the most high-profile example of a failed lobotomy, and she was just one of Freeman’s many patients over his 28-year career at GW, throughout which he performed thousands of lobotomies. The lobotomy was once so ubiquitous at GW that The Hatchet dubbed the University the “home of the lobotomy” in a 1984 feature.

Freeman reportedly performed more than 3,400 lobotomies over the course of his career. The procedure is now considered outdated because of its invasive nature, large chance for error and the discovery of safer, more effective psychiatric therapies.

As students today call on GW to protect the health of disabled students and those who face mental illness, some are looking back in time to analyze how the historic treatment of mentally ill people at GW informs the attitudes of the present and the future. An anonymous Instagram account called “GW Lobotomies” published a post in March criticizing both the lobotomy procedure and GW’s role in allowing the procedure.

The post urged the University to acknowledge “a procedure that has caused such harm to the disabled community in relatively recent history.” They said the University has a “horrible track record” with situations involving mental illness and disability on campus and connected the history of lobotomy in Foggy Bottom with alleged continued negligence for neurodivergent people in the community.

“It is past time for GW to acknowledge this dark past and to pay reparations to not only the individual people/families they impacted, but also to the disabled community as a whole,” the post reads.

University spokesperson Julia Metjian did not return a request for comment regarding the account’s demands for reparations, acknowledgment of the lobotomy’s history at GW and increased disability services on campus.

GW, the “Home of the Lobotomy”

Freeman initially worked as a pathologist at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Southeast D.C., a hospital that specializes in mental illnesses and still operates to this day, after graduating from medical school at the University of Pennsylvania in 1920.

In 1926, Freeman joined GW as a professor of neurology, where he worked directly with patients for the first time. By 1954, the hospital board asked him to resign amid negative publicity toward the lobotomy procedure and the hospital.

Scull said the University should acknowledge the tragic history of lobotomy at GW, even though there were no “mechanisms in place” in the mid-20th century to prevent the procedures or their negative results given the lack of sound mental health research at the time.

“It’s hardly a badge of honor that this happened, started where it did,” Scull said.

Jack El-Hai, the author of the 2005 book “The Lobotomist” which explores Freeman’s life and lobotomy history, said Freeman joined GW in 1926 when he became interested in psychosurgery and the University offered him a faculty position teaching neurology. Because of him, GW Hospital became the “landing place” and “home” of the lobotomy, El-Hai said.

El-Hai said the GW administration was likely “neutral” on the procedure until Freeman began conducting ice-pick lobotomies in the late 1940s. It was then the University asked Freeman to leave, he said.

“In this case, in the case of lobotomy, what’s to be learned is that irreversible procedures should be tried only with great caution,” he said. “And that experimental procedures should be used on patients only with proper consent.”

An invasive procedure

Known as the father of lobotomy, Freeman developed and popularized the operation. Lobotomies were first thought by some medical professionals to relieve mental illnesses like depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and anxiety in patients with more treatment-resistant cases that might not have been responding to drugs, talk therapy or electroconvulsive therapy.

Freeman was originally inspired by Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz’s “leucotomy” procedure, also known as the prefrontal lobotomy. The prefrontal lobotomy requires two holes to be drilled into the patient’s skull to access the prefrontal lobe, the section of the brain that primarily controls emotions and thoughts. Moniz would win the 1949 Nobel Prize in medicine for his creation of the lobotomy.

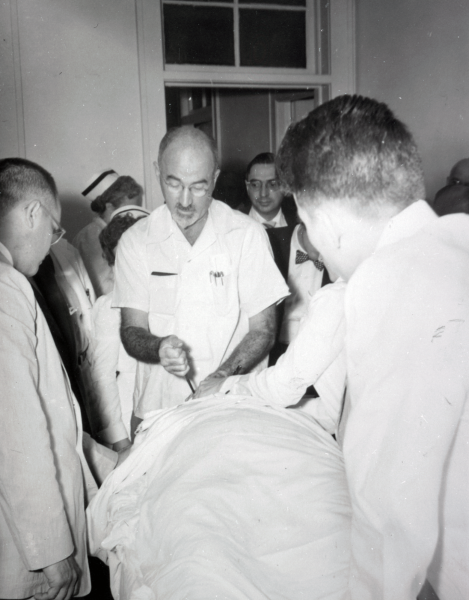

In 1945, Freeman developed the transorbital lobotomy, known colloquially as the “ice-pick lobotomy,” in which he used a sharp tool to cut through the eye socket and sever nerves in the prefrontal lobe. Using this speedy operation, Freeman was able to exponentially increase the number of lobotomies he performed throughout the 1940s and even encouraged psychiatrists who were not surgeons to use this technique on their patients to remedy overcrowding in psychiatric wards.

“In the early days, Jim Watts as the surgeon would perform the surgery, Freeman would sit holding the patient’s hand while the operation proceeded, and he would talk the patient through the operation,” Scull said. “When the patient started to become confused, they stopped cutting. That was purely a trial-and-error thing.”

Some experts in the history of psychiatry argue that Freeman acted justifiably when he pioneered the lobotomy at the beginning of his career because it could have been a promising therapy for incurable cases. But Freeman also insisted that surgeons and psychiatrists use lobotomies even after the development of other methods that were proven to be more effective, like therapies and drug treatments, spurring controversy within the medical world for generations to come.

Experts argue that over the years, Freeman’s lobotomies became less about improving the quality of life for those with severe mental illnesses and instead became a vehicle to prove his medical prowess to the wider academic community and society as a whole.

Scholars have said lobotomy was first critiqued by medical professionals because of questionable patient consent, a substantial reason behind the near-complete discontinuation of its use. But medical professionals have long denounced the procedure itself. A 1972 article published in the Harvard Crimson said a group of students in the Harvard Medical School organized a forum “informing the public of the physical dangers and possible political implications of lobotomies.”

The Crimson article said that some neurosurgeons expressed concern that invasive psychosurgery could result in a “possibility of controlling radicals and social devisers.”

The Crimson article stated that congressional hearings were underway in 1972 to potentially outlaw the procedure altogether. To this day, lobotomies are still technically legal in the United States, though rarely performed.

Christine Johnson, a medical librarian from New York, started a campaign in the early 2000s to rescind the Nobel Prize awarded to Moniz, whose invention of the procedure inspired Freeman’s work. The Nobel Committee ultimately refused to revoke Moniz’s prize, despite the campaign receiving support from people whose family members received the failed procedures.

“How can anyone trust the Nobel Committee when they won’t admit to such a terrible mistake?” Johnson said in the interview with CBS News.

The “last resort”

Experts described the procedure as a “last resort,” performed on those who may have seemed like they had no other path to recovery.

In “Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter,” Larson said William A. White, the superintendent of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, denied Freeman and Watts’ requests to perform lobotomies at St. Elizabeth’s. Larson said White was concerned that patients and their “often-desperate” families could not be trusted to make well-informed decisions about the risky operation.

Freeman’s motivations behind his development of the lobotomy — and more importantly, his incessant push for the mainstream acceptance of the procedure — are difficult to pinpoint. El-Hai said Freeman grew up in a medical family — his grandfather William King once served as the president of the American Medical Association during his respective years as a brain surgeon.

El-Hai said Freeman “remained loyal” to the operation until the end of his life in the early 1970s, long after other medical professionals who originally championed lobotomy abandoned the surgery. It especially paled in comparison to other psychiatric medications like antidepressants and antipsychotics that gained widespread use in the 1950s.

Even after GW asked him to leave in 1954, El-Hai suggested Freeman’s pride led to his persistence in promoting the lobotomy.

“He wanted to be known as someone who had achieved a lot, broken new ground, gone where other doctors had not gone before,” El-Hai said. “I think that’s why lobotomy was so important for him to continue talking about and performing.”

Jenell Johnson, an associate professor of rhetoric, politics and culture at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and the author of “American Lobotomy,” said medical professionals must interrogate the legacy of lobotomy and other controversial procedures to improve the future of the medical world.

“It’s a complicated thing about how it is that we learn lessons from the past to shape the kind of future that we want to see,” Johnson said. “So this is why things like memory and public memory really matter.”

The medical school dedicated four oil paintings of faculty members in the spring of 1970, highlighted by canvases of Freeman and Watts. The portrait of Watts, by the painter Roberto Fantuzzi, featured the neurologist in a medical coat, his right hand holding a pipe, his left resting on a human skull.

The portrait hung in the Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library for years, according to El-Hai and Johnson, but can no longer be seen in the building. When asked where the portrait is today, the University did not return the request for comment.

“Few people were indifferent to Walter Freeman,” Watts wrote about the surgeon after his death. “He thrived on controversy.”