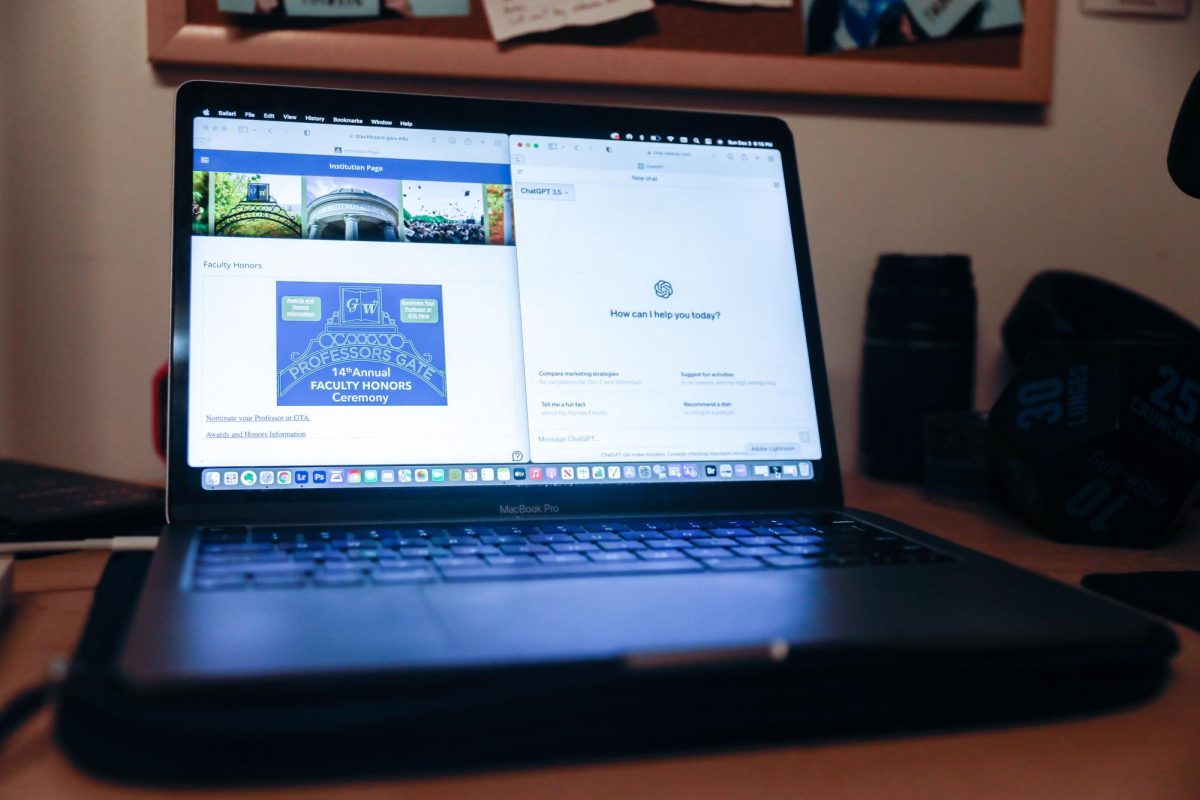

Amid a recent rise in reports of student academic integrity violations, faculty said they are adjusting their course structures and testing policies to prevent and confirm suspected cases of cheating linked to artificial intelligence tools.

Professors said they’ve altered their assessment structures to reduce cheating with AI and identify students misusing the technology but are struggling to develop and enforce individual policies without receiving further support from the University. Christy Anthony, the director of the Office of Student Rights and Responsibilities, said the office this fall has seen an increase in cases of cheating, the category of academic integrity violations that typically involve the misuse of AI.

The Office of the Provost released a set of guidelines for AI use in April that by default banned the use of AI on work submitted to professors for “evaluation” and requested that faculty explicitly outline their own AI use policies in syllabi if they preferred to uphold different AI rules.

Cheating includes the use of unauthorized materials during an academic exercise, while plagiarism is defined as the misrepresentation of ideas as one’s own, per the Code of Academic Integrity. Anthony said the increase accounts for several instances of cheating that each involved a “large number” of students in the same class but that not all violations included reports of AI use.

“This fall, the first since generative artificial intelligence was broadly available at little to no cost, Student Rights & Responsibilities has seen an increase in cases under ‘cheating’ without seeing a similar increase across other categories of academic integrity violations such as plagiarism,” Anthony said in an email.

Anthony declined to comment on the number of academic integrity violations reported this fall compared to previous years and if faculty have expressed recent concerns to the office about online test-taking and AI misuse. She said the office shared information with faculty about preventing academic integrity violations and using AI in the classroom and that they will continue to provide support when needed.

With reports of academic dishonesty on the rise in their courses, faculty said they are modifying their testing structures and working to identify signs of AI misuse in coursework. Professors said despite the provost’s guidelines, GW’s measures to confirm academic integrity violations and develop individual use policies remain vague.

Ronald Bird, an adjunct professor of economics, said he has increased the number of questions on his tests because students who rely on looking up answers using ChatGPT score highly on the first few questions but don’t have time to finish.

“I tend to give more questions so that you’ve got to know something so you can move through them fairly rapidly,” Bird said.

He said he has seen a “couple of instances” where a student doesn’t submit the exam at the end of class and revises their answers after leaving the room. Bird said he can see the timestamps for every answer change because he tests through Blackboard, the University’s primary online education platform.

He said GW should better assist students and faculty with their use of testing technology to combat cheating like Lockdown Browser, a tool that restricts access to other tabs during assessments. He said many students struggle to download the software to their personal devices, which complicates requiring its use.

“Neither the students nor the faculty have been provided with routine and thorough instruction about how to use the technology effectively,” Bird said.

Eric Saidel, an assistant professor of philosophy, said he can identify work produced using AI tools when the paper uses “more sophisticated” language or includes examples that the class did not discuss. He said it is difficult to determine cheating through AI compared to traditional plagiarism because he cannot find a copy of the work online.

“I’m sure I’ve had students who have plagiarized who I have suspected but not caught because I couldn’t prove it,” Saidel said.

Robert Stoker, the associate chair of the political science department and a professor of political science, public policy and public administration, said this summer he decided to prohibit AI use in his classes and that professors in the political science department consulted one another, researched and drafted individualized AI policies. He said professors need to clearly enforce expectations for AI use because the lack of a standardized University policy forces students to receive different instructions on AI use in each of their classes.

“One of the reasons why it’s an issue is that the University doesn’t yet have a specific policy on AI, except to tell faculty that they should be clear about it,” Stoker said. “And so that’s the first thing that’s important, you have to have a clear policy in every class.”

Stoker said he aims to prevent cheating by administering tests in class and requiring students to clear their desks. He said he allows students to collaborate on papers and out-of-class assignments when he can’t ensure he will be able to detect when students consult each other.

“What I want to really avoid is a situation where some students can take advantage of an opportunity and other students cannot, because then I’m not protecting the honest students and that, to me, is the most important thing about academic integrity,” Stoker said.

Stoker said he doesn’t often observe academic dishonesty with papers written outside of class because he provides nuanced prompts that AI tools are not equipped to answer.

“If you give people something not quite so mainstream and that is a little more challenging of the conventional wisdom, then the AI tools don’t work very well for them,” Stoker said.

Alexa Alice Joubin, a professor of English and a Columbian College of Arts & Sciences Faculty Administrative Fellow working on a project about AI in higher education, said she helps faculty struggling to identify cheating with AI tools by developing assignments that aren’t compatible with the technology and sharing ways to use the technology positively.

“One of the cases that came to me is in the Corcoran School and the assignment asked students to read an article and summarize it,” Joubin said. “As you can imagine, it’s perfectly set up for AI.”

Joubin said faculty are “incredibly frustrated” because the online AI detection tools designed to help instructors check for AI-generated work can’t reliably catch instances of the academic dishonesty. She said academic integrity cases related to AI don’t often escalate because suspecting faculty lack “hard evidence.”

Joubin said the University is developing further resources for faculty somewhat slowly and she is providing individualized advice to a lot of faculty who don’t know how to monitor AI use.

“I even contributed my AI policy, my sample syllabi, but it’s not quite out there yet,” Joubin said. “There could be kind of a centralized place for people to find resources more easily. Right now, it’s at a very individual level.”

Rachel Moon contributed reporting.