Kamau Louis is a member of the class of 2022 and former opinions writer for The Hatchet.

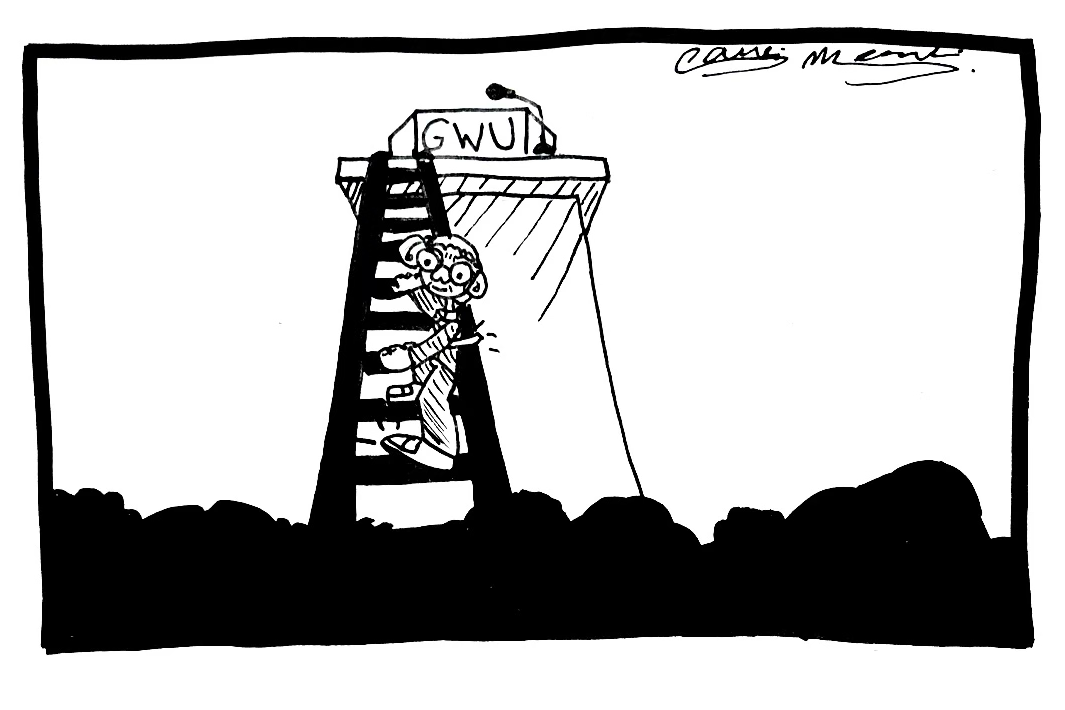

Though I graduated from GW last semester, this University has a special place in my heart. It’s where I had my first love and first heartbreak, found brotherhood and made lifelong friendships. Yet, despite priding themselves on creating change on campus, GW community members are missing the problem in front of them. In 2022, I was one of the only 779 Black men in GW’s total student population of 25,939, just three percent of the student body.

The inclusion of Black men in the University community is key to fostering a much more equal society, but GW’s population of wealthy, privately educated and suburban students has likely had limited experiences with Black people. And it shows. In spring 2020, a freshman told me I was her first Black friend – we’d only known each other for two weeks. I have been confused for other Black men on campus by other students, some of whom I don’t share a resemblance with at all. These experiences were very shocking and negatively affected my idea of my individuality.

It can be isolating when you look around and no one looks like you. And while I as a Black man have been accepted and greeted with warm welcomes the majority of the time by other students, my peers have also greeted me with awkward smiles or an air of nervousness. Subconsciously, I know some people might stereotype me as violent, aggressive and even as a sexual predator. These stereotypes have led to many Black men and boys dying, like in the case of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, whom a neighborhood watch member named George Zimmerman shot and killed 30 minutes away from my home in Florida in 2012. These thoughts are always in the back of my mind and affect how I interact with others.

All of these subconscious fears can be frustrating and stressful, but as a Black man, you sadly learn that this is the status quo in predominantly white spaces like GW. But Black men who make it to college are the lucky ones, in a twisted way of thinking. Black families, who have lower median household incomes than Asian, white and Hispanic families, can’t always afford the cost of college. We can end up entangled in the criminal justice system – by age 23, 49 percent of Black men have been arrested, according to a 2014 study, and Black men are especially likely to be imprisoned, even as incarceration rates have decreased since 2006. And victims of gun violence are mostly young, male and Black.

I have heard white students discuss their desire to be changemakers, but that doesn’t always pan out in reality. In a class discussion about a proposal from Georgetown University students to pay a $27 semesterly fee in reparations to the descendants of the slaves Georgetown sold in 1838 to avoid bankruptcy, my classmates got mad that other students would have to pay the fee instead of Georgetown as an institution. College students get far more frivolous things for $27, like overpriced cocktails, Ubers and fake IDs. And even though my Caribbean ancestors had nothing to do with the enslavement of the Black people who built Georgetown, I wouldn’t mind donating to help people who have suffered from generational poverty and inequality over the decades. How do these students think they’re going to make change and help people when they won’t put their money where their mouth is, let alone venture to the Target in Columbia Heights because it’s “shady”?

To cultivate a space for Black men at GW where they can feel more comfortable and accepted, first increase the amount of Black male students and Black students overall at GW. Considering that 45.8 percent of D.C. residents are Black as of 2022 according to Census data, GW should start making more inroads to predominantly Black public high schools in the area, like Dunbar High School and Jackson-Reed High School. In 2022, only 66 undergraduate students out of GW’s 1,690 students from D.C. were Black men. Granted, GW offers a $7,500 scholarship called the District Scholars program to D.C. residents but those funds only cover a fraction of tuition.

The University also competes with Howard University. At D.C.’s illustrious historically Black university, 2,418 students were Black men and 2,238 students were from D.C. out of a population of 12,886 students in 2022. Like every university, Howard rejects many talented applicants who can’t afford its $52,000 tuition. I ended up attending GW because it offered enough financial aid that made the cost of attendance more affordable than Howard.

Second, increase the amount of Black faculty at GW. To its credit, 18.7 percent of GW’s faculty is Black, while Black faculty make up only six percent of college faculty nationwide. But hiring more Black professors along with other minority groups can only help improve GW with a more diverse range of perspectives. Seeing accomplished men who look like me, like geography professor Dr. Moses Kasanga and political science professor Dr. Andrew Thompson, has made me feel comfortable and like I belong at GW. And Vice President Charles Barber and Provost Chris Bracey, both of whom are Black men, hold high positions within the University’s administration. The brotherhood and connection that I felt with other Black men on this campus feeds into that sense of belonging as well. To see people who look like me gives me hope that I can reach such heights.

From professors to students to staff, the people I met at GW for the most part have made an effort to make this University feel like a home away from home for me. I did feel at home at GW, but this home was not always perfect. Yet working to improve your home is all that matters. GW has a bright future ahead if it can close the gap for Black men.