Milken Institute School of Public Health researchers found the racist historic practice of redlining has made finding present-day behavioral health services for communities of color more difficult.

Researchers created a database to geolocate the number of behavioral health clinics and provide evidence of the lasting impact of systemic racism. The study found that formerly-redlined areas with communities of color have fewer behavioral health clinicians than areas that did not undergo redlining, with one county having 20 times fewer psychologists, counselors and therapists than non-redlined areas.

Redlining became a practice in the 1930s across the United States where the federally-sponsored Home Owners’ Loan Corporation designated neighborhoods as financially low or high risk for banks to determine which areas in cities were safe investments for loans.

Clese Erikson, the Deputy Director of the Health Workforce Research Center and the study’s lead research scientist, said the study exposes the modern-day effects of systemic racism that linger through access to mental health services via transportation barriers that make traveling long distances to appointments not possible for some.

“I wanted to be able to provide some evidence around the lasting impact of systemic racism,” she said. “It really seems like it’s something that is just increasingly coming to the forefront of national attention.”

The HOLC would designate wealthier and predominantly-white neighborhoods as low risk, which it would color code as green or blue, while areas with Black and immigrant communities were rated as high risk, color-coded yellow or red. Erikson said a high risk designation caused community members to not be able to receive loans while those in low-risk areas were able to build generational wealth.

Nicholas Anastacio | Graphics Editor

She said her research team at the Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity – an institute dedicated to advancing health workforce equity – had previously developed a database in 2019 of behavioral health clinicians, like psychiatrists, addiction specialists and therapists, and could compare the database to maps of the HOLC designations.

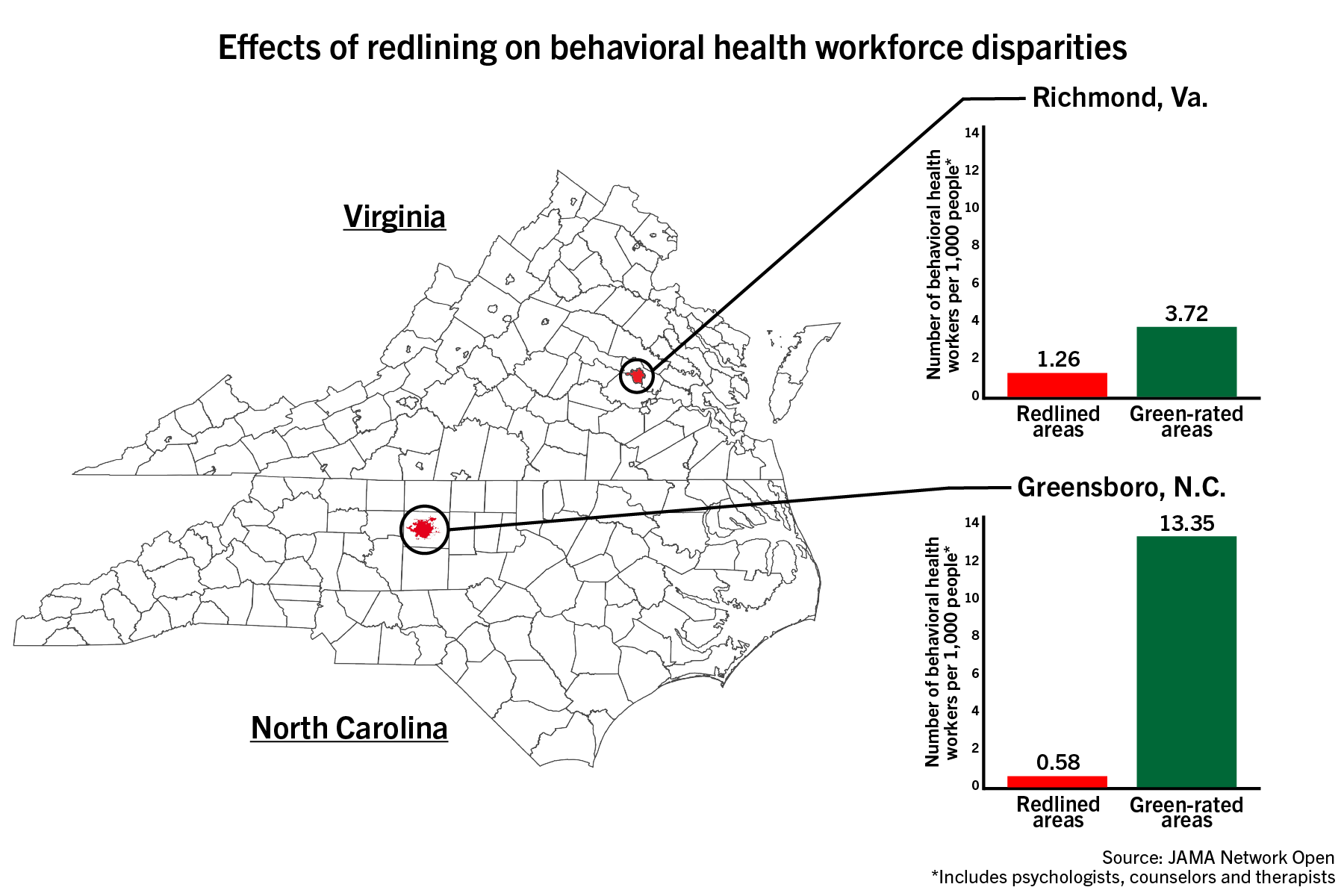

The study examined Richmond City County in Virginia and Guilford County in North Carolina, which are both designated by the Health Resources and Services Administration – an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services – as mental health professional shortage areas.

Formerly-redlined areas in Richmond City County have just below three times less psychologists, counselors and therapists than formerly “green” rated areas while those in Guilford County have over 20 times less.

“If we can see what’s happening and have the evidence in front of us, then we can actually identify policies that might better respond to and address long-standing issues related to systemic racism,” Erikson said.

Experts said policy solutions include mental health parity – requiring equal insurance coverage for both mental and physical health – as well as diversifying the behavioral health workforce to include more members of redlined communities.

She said the researchers excluded higher rates of mental health needs and transportation barriers from the data they studied because of the preliminary nature of the study, which kept the study from completely conveying all of the challenges communities impacted by redlining face in receiving behavioral health care.

“We may actually be underrepresenting the challenges these communities face in terms of access to behavioral health,” Erikson said.

She said her team plans to expand its study to include an additional 200 cities recorded in Mapping Inequality – a website that shows redlining maps across the United States – and data on transportation times via walking, public transportation and driving to more clearly depict the systemic effects of redlining.

Healthcare inequity experts said the study’s findings help supply evidence on the long-term effects of systemic racism.

Ruth Shim, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at University of California, Davis, said the study shows redlining involved large scale divestment from communities of color that continue to harm them today.

“The study, I think, does a really good job of confirming what we’ve kind of already always known and have always suspected, which is that these policies that are set up to segregate and to discriminate against certain populations effectively did that,” she said.

Shim said redlining labeled communities of color as unworthy of federal benefits and new businesses, which minimized the number of hospitals and health services available to them. Shim said maps of redlining all across the United States align with maps of health inequity, educational inequity and poverty.

“These are the lasting effects of residential segregation, and you see them showing up in almost every aspect of our life, even in present day,” Shim said.

She said Black and Latino communities have low rates of behavioral health services access, specifically mental health and addiction treatment. Shim said the main barriers these communities face are costs and availability due to the location and high price of behavioral health services.

“It’s really important for studies like this to continue to document an ongoing problem, because lots of people would like to think that we’re in a post-racial society where there is no discrimination, and there is no structural racism,” Shim said. “And that’s just not true.”

Matthew Tierney, a professor of community health systems at the University of California, San Francisco, said levels of depression and substance abuse remain similar between demographics, but there are “huge fluctuations” in access to treatment due to racial inequity.

He said marginalized communities in general have less access to behavioral health services, like substance abuse treatment, than predominantly white communities do.

“The people who have the toughest time with access to behavioral health care are those who have the toughest time with access to other types of social services,” he said.

Tierney said expanding community pharmacies to include more health services would make behavioral and health services more accessible to disenfranchised communities.

“We have to think about outreach to community centers, and to churches and to places where people trust and know,” he said. “I think that could make a huge difference in making behavioral health services accessible.”