The rollout of the University’s U-Pass system represents a much-needed success for students and Metro, but the D.C. area transit agency continues to face serious issues. After a train derailment in October, Metrorail has experienced delays and long wait times, while the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has meant fewer riders, sick employees and a looming cash crunch. Moreover, Metro General Manager Paul Wiedefeld recently announced his decision step down from his position over the summer.

Metro is in crisis – or rather, crises. Interconnected operational, safety and fiscal problems have left tens of thousands of commuters in transportation limbo. It’s hard to fault anyone who’d rather avoid public transportation than rely on the agency’s teetering rail and bus networks. Metro riders deserve a transportation agency that functions. As more substantive solutions remain in development, Metro can begin to move past these crises by returning to its original mission – connecting people and places.

Despite the precautions taken by Metro and other agencies, riders have abandoned public transportation systems en masse during the pandemic. A drop in passengers translates to a drop in fare revenues, a major source of income for Metro. Put simply, people who don’t ride don’t pay. Yet as the pandemic wanes – or at the very least, becomes endemic – those riders haven’t returned. The federal employees whose commutes are so key to Metro’s operations have transitioned to telework and working from home. They aren’t avoiding riding – they just don’t need to.

In response to Metro’s budget shortfalls, congressional stimulus and relief legislation has included tremendous sums of money to keep the agency solvent. But such relief is only temporary: without further federal action authorizing additional spending, that emergency funding appears set to expire. While politicians in and around the District, like Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., try to rally support for more funding, Metro management sees the agency hurtling toward fiscal disaster.

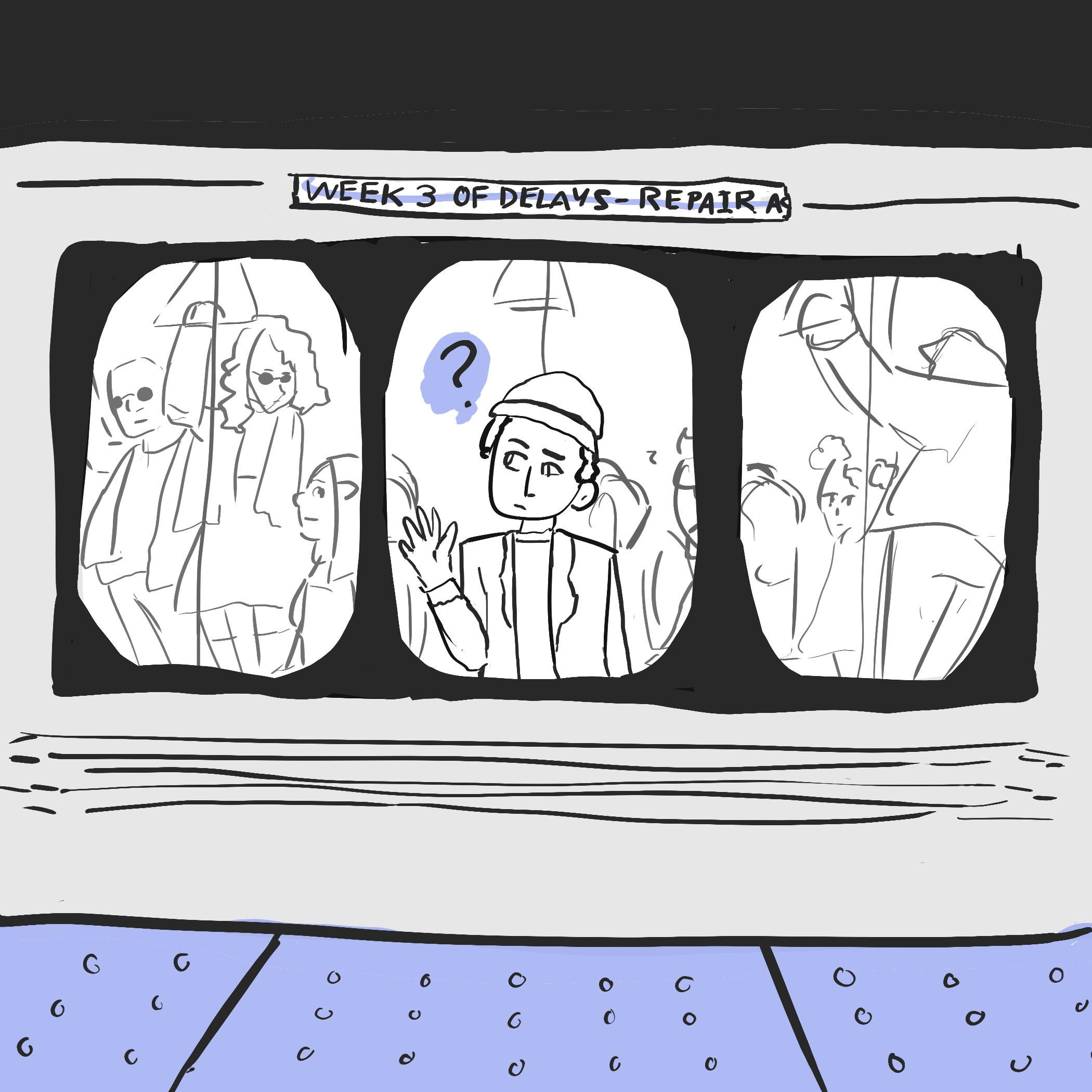

Sofija Juodaitis | Cartoonist

The only thing worse for a cash-strapped transit agency with low ridership is an event that requires costly investigations, further shakes the public’s confidence and keeps riders off trains. Enter the October 2021 derailment. While there were no fatal injuries, this accident could be the death knell of Metro – it is a microcosm of the crises the agency is facing.

The October derailment outside Arlington occurred because the train’s wheels moved out of position between the tracks, an issue Metro has been aware of since at least 2017. In response, Metro pulled all its 7000-series cars out of service. Five- to 10-minute waits immediately jumped up to 20 to 30 minutes as older cars were pressed into service to fill the gap. After making a brief return in December, the 7000-series cars were again pulled out of service after Metro deviated from the instructions of the safety commission overseeing the investigation into the cars. An avoidable safety issue has set Metro further behind as it attempts to climb out of its pandemic lull.

Yet it takes more than empty buses and trains to run a network. COVID-19 has struck Metro employees hard, especially amid D.C.’s Omicron surge. Pandemic-related workforce shortages only compound the delays and service outages affecting the region, which are particularly severe on Metro’s bus network.

Additionally, a 2020 audit by the Washington Safety Rail Commission urged Metrorail to address an ongoing culture of “racial and sexual comments, harassment and other behavior.” Combined with an abusive workplace culture and sense of complacency, Metro is simply not in good health. While earlier initiatives have brightened stations and replaced crumbling platforms, Metro itself needs an overhaul. Though it’s difficult to shepherd the massive concentric bureaucracies that comprise Metro to a singular solution, especially as these crises continue, it is clear that it must do something for riders with no other options – or those who simply prefer it over other modes of transportation.

Staff shortages and an already tight schedule would make replacement bus services, like those offered between stations closed for platform improvement projects, largely unfeasible. Walking and biking, particularly during the winter months and especially for those with mobility needs, is a nonstarter. Pouring money into hiring and training new staff, whether to operate trains and buses or to accelerate the rate at which the 7000-series cars reenter service, is equally unlikely.

If policy solutions and large financial commitments remain elusive, perhaps the attitudes that inspire that policy can shift. Upon its debut in 1976, Metro promised an exciting, effective glimpse into a future that was quite literally a stop away. Whoever succeeds Wiedefeld should leave us proud of Metro, not cursing at it.

In a city that can sometimes feel like it houses more three-letter offices and guarded government buildings than people, Metro does, albeit sometimes infrequently if at all, connect us to one another. For residents around the region, it connects them to family, friends, loved ones and workplaces. For GW students, Metro is our way out of the confines of Foggy Bottom or the beginning of our journeys to and from home at the beginning and end of each semester.

I intend to use my U-Pass this semester. I only hope Metro will be able to get me there – and that it’ll be around long enough to do so.

Ethan Benn, a sophomore majoring in journalism and mass communication, is an opinions writer.