GW has long been known for its location, situated closer to the legislative heart of the United States than any other higher education institution in the country.

Freshmen live just blocks from the White House and the National Mall, and all of the Smithsonian museums are a half-hour’s walk or a short Metro ride from campus. For many students, GW’s location in the nation’s capital is a major reason they choose to come here. So when GW closed its residence halls last March, a great number of students understandably decided they would move back in the fall to try to find a semblance of a normal college experience.

But returning to D.C. put students in an awkward position as officials only planned to offer 500 beds in the fall and an additional 1000 beds in the spring. As a result, many students found themselves turning to off-campus housing. As they moved into their off-campus living arrangements, many found their new abodes to be both more affordable and of better quality than the residence halls they left behind. The COVID-19 pandemic era has made it abundantly clear that GW’s residence halls are exorbitantly priced and, despite the premium, leave much to be desired.

It’s long past time for officials to finally address the University’s housing problem. To do this, they have two real solutions – they can reduce the price of housing to make it a better value or remove the three-year residency requirement, forcing GW’s residence halls to compete with the surrounding properties.

The poor value of GW’s student housing isn’t a new problem. Residence halls are so overpriced and so low-quality that some freshmen and sophomores have even falsified their documents with the University in order to secure a housing exemption. The reason many students resort to such a drastic measure is the University’s housing policy which requires first, second and third-year students to live in on-campus housing, with the exception of those who plan to commute or need a residency exemption. In the District, this policy is only shared by Georgetown University, while Howard University, the University of the District of Columbia and American University have no such restrictions. It’s also worth noting that Georgetown and GW both have average on-campus housing costs, including room and board, of more than $15,000 per academic year. Howard is close with an average annual housing cost of about $14,000 per year, while UDC and American both tout residence hall costs of about $11,000 per year.

It would appear then that Georgetown and GW’s residency requirements are structured to make as much money as possible for their respective universities. Indeed, for some rooms like the five-person, five-bedroom unit in South Hall, GW will make more than $12,000 per month, per room — money they will functionally always receive, thanks to their three-year residency requirement.

By requiring three years of residency, GW both sidesteps all competition in the student housing market and guarantees demand for their properties, making student housing less an accommodation and more a price-gouged profit scheme. By lowering residence hall prices or removing the residency requirement, officials could show that they aren’t trying to price gouge residence halls and actually care about making on-campus housing a good value for its occupants.

Each student at GW spending the whole academic year on campus will be paying anywhere between $1,900 and $2,400 per month for the privilege of living in GW’s housing. While this might just seem to be the cost of big-city living at first glance, a quick search yields dozens of studio apartments in Foggy Bottom for less than $1,500 per month. The neighborhood search platform Niche reports an average rental cost of $1,846 per month in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood. Clearly, an average housing cost in Foggy Bottom, which is below the minimum housing cost at GW, indicates that officials have gouged the price of residence halls on campus. It’s further worth noting that the $1,846 average rental cost is for one person, meaning that with a roommate or two, students can lease an apartment for two or three thousand dollars per month and still make out in the green by hundreds or even thousands of dollars. The considerably lower price tag alone makes it easy to see why some students are willing to find some loopholes to live off-campus, even when they’re not supposed to — but it’s far from the only reason.

The quality of GW’s residence halls is likely another factor that leads many students to seek off-campus housing. Before its closure for remodeling, Thurston Hall regularly showcased the University’s shortcomings in residence hall maintenance. Living there my freshman year, the bathroom ceiling of the room across the hall collapsed. It was several hours before any efforts were made to clean up the rubble, and even after the collapse, it took three more days for maintenance to come and fix the buckling ceiling in our own bathroom and closet. Mold has also been a recurring issue in University residence halls, leading officials to have to hire crews and conduct weekly cleanings to remediate mold in Thurston. The University even had to relocate summer housing residents due to a mold outbreak in Mitchell Hall, which it was later sued over. While these maintenance oversights don’t necessarily permeate every residence hall on campus, they do little to build confidence in the University’s ability to maintain their residences.

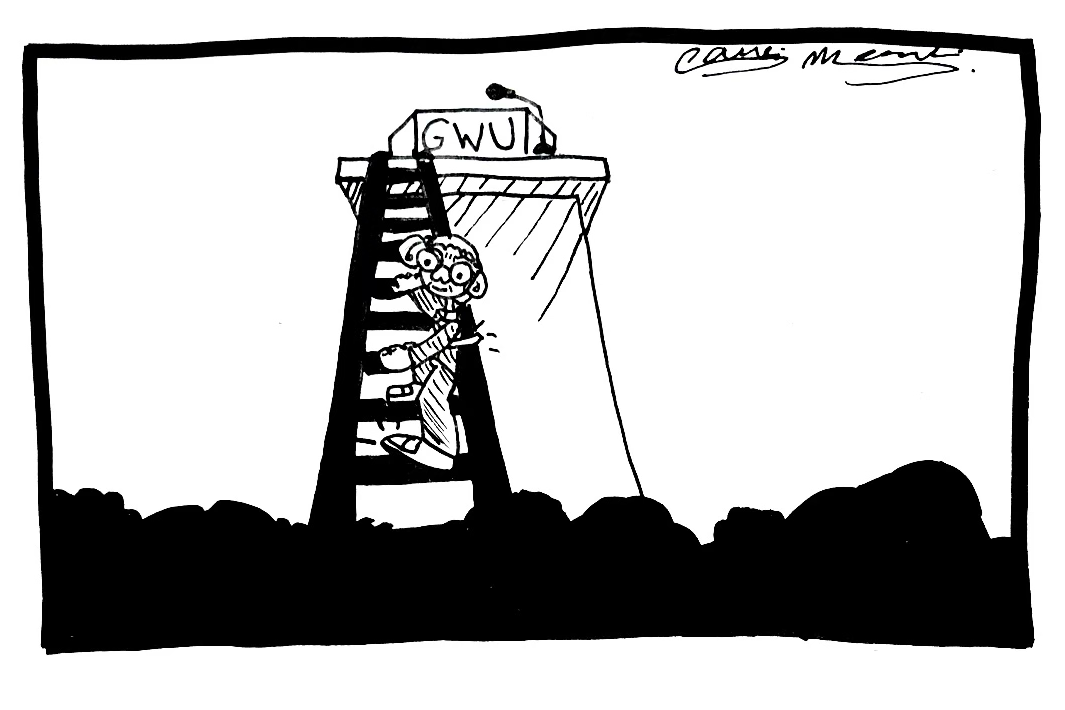

Considering all of this, it’s plain to see that students want to live off-campus because officials have failed to make residence halls a good value for the GW community. Why would a student live on campus when they could live in more comfortable off-campus apartments for half the price? It’s a trick question — they wouldn’t. Clearly, GW’s residence halls are overpriced for what they provide, and until officials lower housing costs or increase residence hall quality, the residency requirement serves only as a testament to the University’s greed.

Kyle Anderson, a sophomore majoring in political science, is an opinions writer.