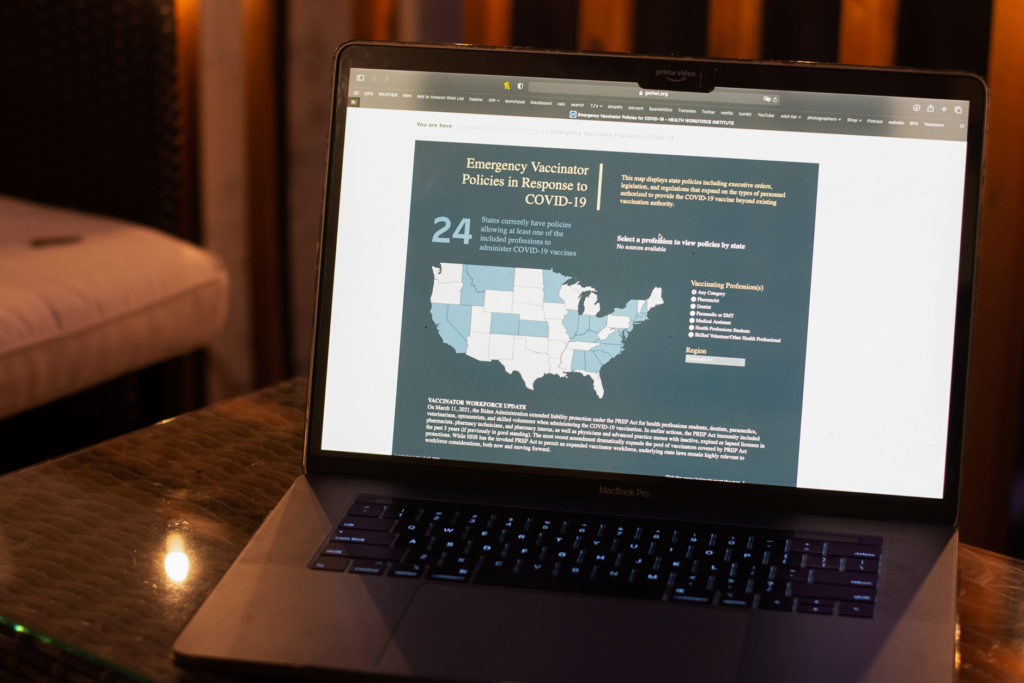

A team of Milken Institute School of Public Health researchers compiled an interactive map late last month showing which health professionals in each state are allowed to administer COVID-19 vaccines.

The map reveals that 24 states have implemented emergency legislation to expand authorization to groups of professionals, like dentists and paramedics, who aren’t typically responsible for dispensing vaccines. Julia Strasser, a senior research scientist at the public health school and the lead researcher on the project, said the map could inform public health leaders on neighboring states’ policies to guide their own state’s distribution guidelines and influence their rollout plans.

Strasser said she hopes the information presented in the map can inform state leaders about how expanding the number of vaccinators can reduce bottlenecks in distribution. She said about half of the states have implemented policies to increase the number of vaccinators in light of the pandemic.

“That suggests to us that the other states could also implement similar policies, and that would hopefully dramatically expand the vaccinator workforce in these other states as well,” she said.

The map allows users to click on a specific state to see the types of professionals who are authorized to administer the vaccine in that state. The map also links to the specifically approved legislation that authorized the respective groups of professionals to provide the vaccine.

Six Milken researchers – Patricia Pittman, Meg Ziemann, Noah Westfall, Rachel Banawa and Nicholas Chong – collaborated with Strasser to create the map, according to the map’s website.

The map shows that 15 states, like California, Nevada and Colorado, have authorized dentists to administer vaccines. Thirteen states, like Nebraska and Ohio, have authorized other “skilled volunteers” to administer the vaccine, according to the map.

Strasser said some states have allowed students in health-related fields or retired health care professionals, who have completed a base level of training, to administer the shot. She said these steps can help speed up states’ vaccine rollouts.

“What we’re seeing is that with a little bit of training and a little bit of guidance, and sort of willingness, that people like hazard health professions, students can do this,” she said. “And it’s sort of this untapped potential to be able to expand this workforce.”

The PREP Act, which was passed last month, authorized the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to expand the number of individuals permitted to administer the vaccine.

Georgia, Virginia and California have struggled to distribute their COVID-19 vaccines after receiving shipments in January because of a lack of capacity to administer the shots, CBS News reported.

“In general, of course, it is helpful to have the federal government be a leader in this area,” Strasser said. “But we also recognize that state officials and state policymakers may choose to act on their own in addition to federal guidance.”

Experts in public health and medicine said expanding the authorized workforce could help speed up distribution, but the move should be paired with thorough training for professions who haven’t conducted vaccinations before.

Bruce Y. Lee, a professor of health policy and management at the City University of New York, said the map can be helpful for policymakers and public health workers who want to find ways to improve vaccine distribution. But he said expanding the workforce too broadly can decrease the quality of vaccine distribution, through contamination and other unsafe practices, if some are not properly trained.

“In terms of vaccines, having this type of policy map to help people understand differences – in this case, differences in terms of vaccines – and vaccination is important,” he said. “Anything that gives us a national view of how things might be similar or different among different faces is helpful.”

Thomas Denny, the chief operating officer of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute at Duke University, said compiling state-specific information in a map format can help health leaders learn from other states’ successes or failures in their vaccine rollouts.

“Anything that helps identify successes, maybe not successful approaches, is helpful to policymakers,” Denny said. “For example, if one state is mobilizing a group of health care workers to provide vaccinations and it turns out that it works wonderfully, that can be used as a tool as a learning lesson for others.”

He added that COVID-19 vaccinators recruited from outside of the industry may need more time to reach proficiency.

“There are a number of different people within health care professions that could be easily trained to do that,” he said. “Whether or not you take people outside of the health care profession, you may be able to train them, but it may take more time and more energy to get the same level of proficiency.”

Michelle Vassilev contributed reporting.