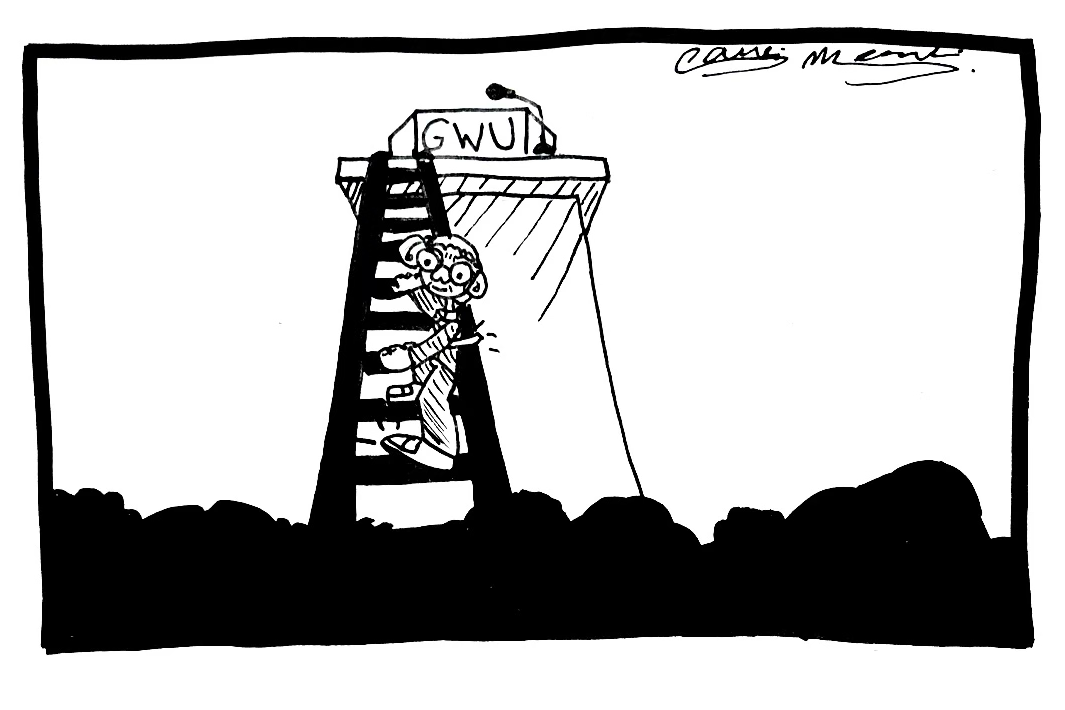

Last fall, as GW sought to limit student travel during breaks, officials decided to reduce the duration of fall break. This decision may have limited students’ travel plans, but the abbreviated rest left many students, myself included, feeling winded.

This March is an auspicious month – one year since the beginning of pandemic-related quarantines and isolations. In March last year, I embarked on a 28-hour long journey home from my study abroad. I understand the desire to shake off the fog of pandemic fatigue and go on an exciting voyage to a warm, sunny place and do nothing but lay on the beach and soak in some Vitamin D. But as we have seen repeatedly over the last year, with an increase in travel comes an increase in coronavirus cases.

Flying around the country or abroad is irresponsible and needlessly endangers airline workers and local communities. Some trips are necessary for mental or physical health reasons. But earlier this month, spring breakers swarmed Miami Beach, where the surrounding community has already been hard hit by the coronavirus. Additional tourism not only brought more cases to Florida, but it also exported the virus when spring breakers left the beach. Your travel could have waited, and it can continue to wait until enough of the population is vaccinated.

I, too, would have loved to have gone to a Florida beach or returned home to visit my parents in Texas. I could not find a way to reconcile the increased risk of transmission with the relatively unnecessary nature of these wishes. I have not seen my parents since July, and I miss them dearly. One of my grandmothers lives in Florida, and she has been coping with this pandemic almost entirely on her own. If my 89-year-old, twice-widowed grandmother can learn to accept isolation and resist the urge to see her children and grandchildren, I am convinced that teenagers and 20-somethings could have found ways to unwind that did not include hopping on an airplane to go drink at some faraway beach.

Time and again, I find myself aghast at the arrogance and selfishness of some of my peers. Their actions suggest little regard for the health and safety of others amid a global health crisis not seen in 100 years. This group of people includes some of my friends, and I have struggled with how and whether or not to continue those friendships. The sheer disregard for others it takes to travel hundreds or thousands of miles in an enclosed space while possibly spreading a deadly virus is pretty astounding.

Students may want to continue traveling as the weather gets warmer, but those trips can wait. Most, if not all, willing and eligible Americans are likely to receive their COVID-19 vaccines by the summer. If we can vaccinate a sufficient percentage of the population, then we can resume air travel without worrying too much about endangering airline workers, family and friends. I am painfully well aware of how difficult this race to get vaccinated is, as well as how dispiriting it is to have to sit and wait for a shot. I am not a health care worker, but I can have at least a passive role in ensuring we beat this virus by staying home and getting tested.

Between racist murders of Asian Americans in Atlanta and another mass shooting in Boulder, Colorado, spring break provided little relief. In all of my classes the week after break, it felt like my peers were dragging. Morale is low, and I do not fault people for wanting a respite in these deadly, depressing times. I only wish they would find safer ways to do so.

Matthew Zachary, a senior majoring in Latin American studies, is a columnist.