Philip Wirtz is a professor of decision sciences and of psychological and brain sciences and a faculty senator for the GW School of Business. Sarah Wagner is an associate professor of anthropology and a faculty senator for the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences. Both are members of the Faculty Senate Committee on Appointment, Salary and Promotion Policies.

Last Friday, the Faculty Senate voted to express “severe disapproval” – rather than censure – of University President Thomas LeBlanc’s decision to hire Heather Swain as GW’s vice president for communication and marketing. Swain withdrew her acceptance of the offer after widespread criticism over her role in the follow-up investigation of the Larry Nassar sexual abuse case. President LeBlanc subsequently sent an email to the GW community in which he apologized “for the distress and distraction that this has caused many in our community.” He noted that “I should have recognized the sensitivities and implications of this hire.”

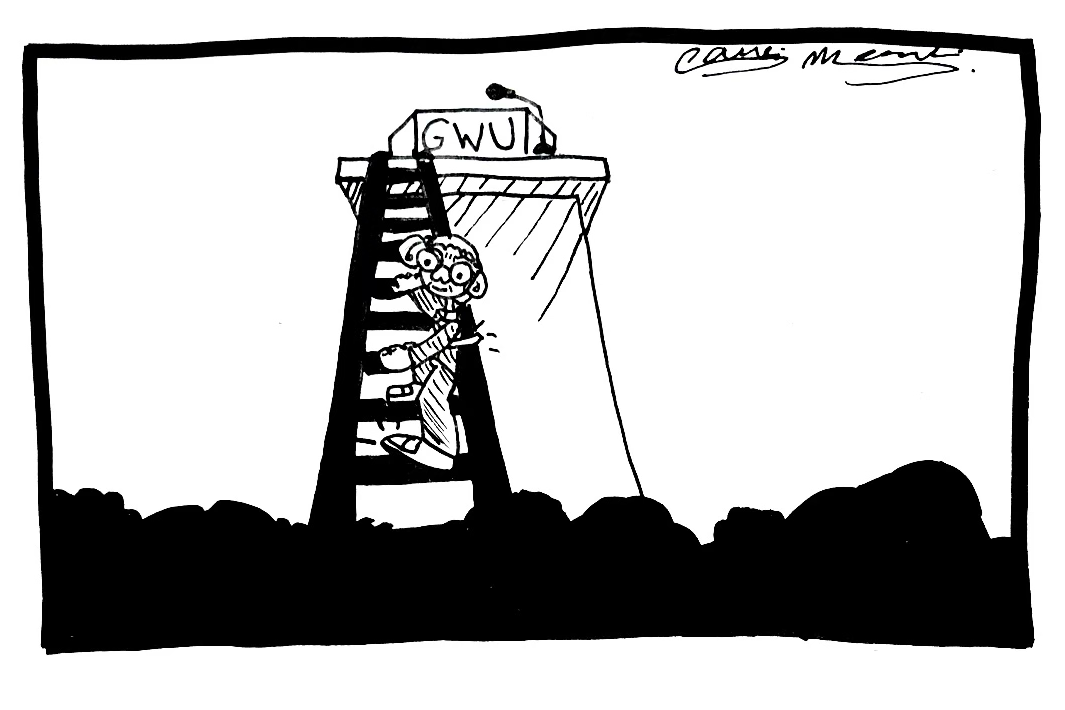

Prior to last Friday’s meeting, the senate commissioned the Senate Appointment, Salary and Promotion Policies Standing Committee to meet with President LeBlanc in confidence to hear his account of the events, timeline and decision-making process that led to Swain’s hire. After fully reviewing these factors in confidence with President LeBlanc, the committee recommended, without dissent, that the senate censure the GW president over the matter. We are two members of the committee and of the senate who dissented from the senate’s decision NOT to follow ASPP’s recommendation. We think the decision to use a term other than “censure” not only weakened the message sent by senators to President LeBlanc but also sent an unfortunate message to the University community and administration.

As correctly reported by The Hatchet, one reason offered during the senate debate for the change in wording was “because [President] LeBlanc provided a full accounting of the Swain hiring process and proposed changes for administrators to vet candidates in the future.” But the logic behind this assertion is problematic: It seems to suggest that, no matter how egregious the behavior, “censure” is inappropriate as long as the individual takes responsibility, apologizes and puts in place provisions which minimize the probability of recurrence. Apart from the fact that (a) the “full accounting” occurred under strict confidence with a committee that included a number of faculty senators, and (b) the new hiring protocol came at the senate’s – not the president’s – request, the assertion signals that the senate will limit sanction about any future misdeeds as long as an offender apologizes and takes steps to minimize recurrence of the behavior. In our view, the degree to which bad judgment was exercised needs to be factored into the severity of the sanction. Knowing the details of the events, timeline and decision-making processes, the ASPP committee determined – after “extensive” deliberation, as reported by ASPP to the senate – that “censure” was the correct word to apply in this case.

The Hatchet article also correctly notes that there was some wariness about censuring the president because the “trustees did not want faculty to censure [President] LeBlanc, preferring that senators voice strong disapproval of the hiring instead,” and that “maintaining a dialogue with trustees and administrators, rather than voting to censure, will enable senators to advocate for faculty more successfully.” From our perspective, the senate needs to be entirely independent of the Board of Trustees. The senate should not be taking positions out of fear that the Board will no longer maintain a dialog with it. To us, that sounds like extortion. Furthermore, privileging the trustees’ interests over those of our colleagues, who elected us to represent them in the senate, undermines not only our ability to engage in shared governance but our standing to do so.

A third reason correctly cited in The Hatchet article for reluctance by the senate to censure President LeBlanc is that it might “impair the senate’s ability to practice shared governance with administrators in the future.” Again, to us, this sounds as if the senate is running away from its responsibilities as the independent unit which speaks truth, even if that truth might not be something the administration wishes to hear.

The Faculty Senate has for many years set the standard for independent expression. To us, last Friday’s failure by the senate to approve a resolution of censure represents an unfortunate departure from that standard. We hope that the senate will soon return to the standards which, in our view, it failed to meet last Friday.

Want to respond to this piece? Submit a letter to the editor.