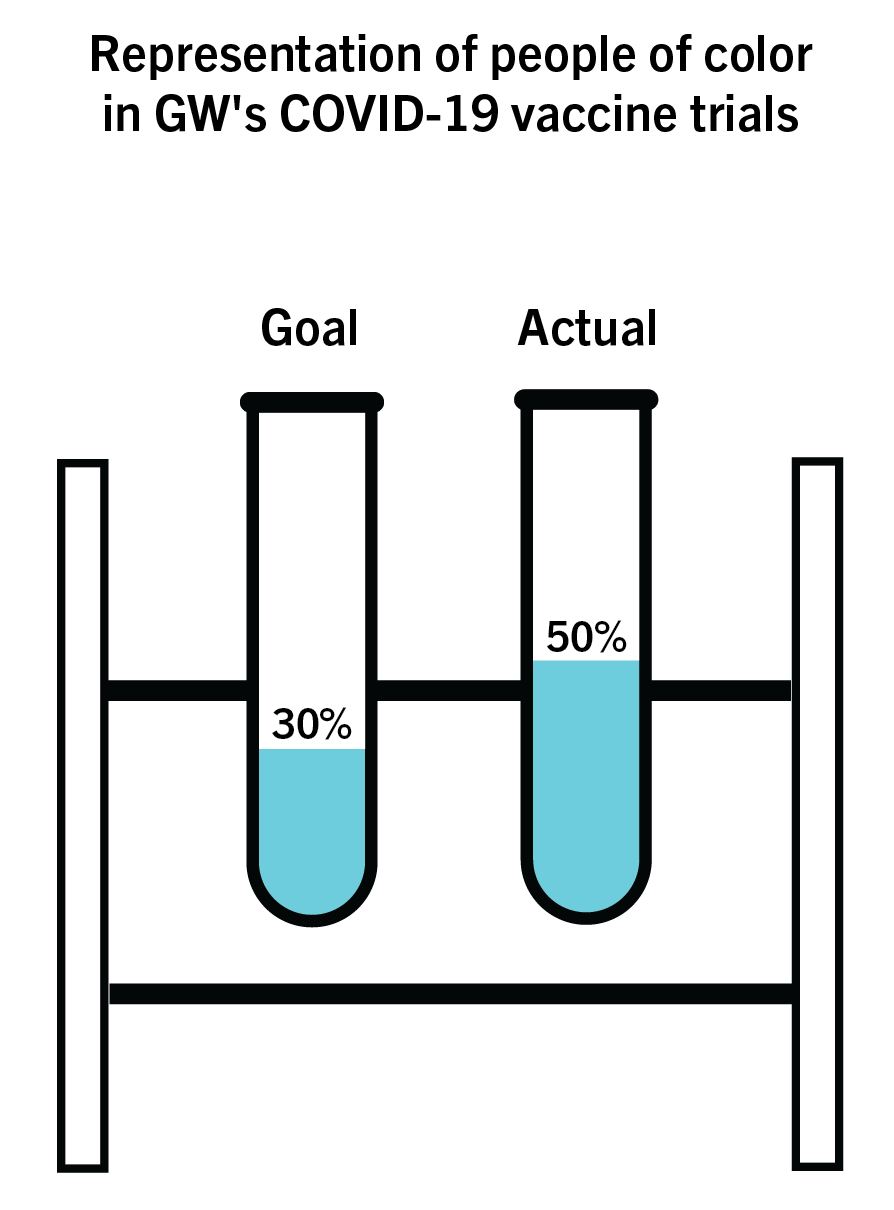

Almost two months after GW launched its arm of COVID-19 vaccine trials, researchers have surpassed their goal for including participants from minority communities as part of their test population.

The researchers aimed for 30 percent of their trials’ participants to be from a diverse background, including African Americans and people from the Latino community, but the trials have surpassed this goal, with about half of enrolled participants being people of color. The research team – led by David Diemert, a professor of infectious diseases – said they’re currently conducting Phase Three of the vaccine trial after the first two phases proved to be safe and showed an immune response.

The team, which includes School of Medicine and Health Sciences professors Marc Siegel and Elissa Malkin and Milken Institute School of Public Health professor Manya Magnus, said testing the vaccine on a sample population that includes Black, Latino and elderly populations ensures researchers prove the vaccine works on those populations, which have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

“If we do not enroll a representative sample in this study, we will not know whether this vaccine is safe and prevents COVID-19 in those most affected by the pandemic,” the researchers said in a joint response.

Sidney Lee | Graphics Editor

The team said they were able to find a diverse sample population using connections from their past work on HIV and a database that keeps track of people who are interested in participating in vaccine trials.

They said they’ve almost reached the 300-person capacity for the number of people who can be enrolled in the trial, and once the last person is enrolled, they’ll follow the participants for the next 25 months.

“There will be several interim analyses as the study proceeds to evaluate for vaccine efficacy, and so it is possible that there will be study results that are released before the completion of the study,” the researchers said.

Black residents have comprised 52 percent of cases and 75 percent of deaths related to COVID-19 in the District, according to a May NPR study.

Vaccines can take 10 to 15 years to research, develop and be approved by the Food and Drug Administration for widespread use, but Operation Warp Speed, a government-funded program implemented to accelerate vaccine trials, has provided the resources to speed up the vaccine development process.

Infectious disease experts said including people from diverse backgrounds in COVID-19 vaccine trials can increase the public’s trust in the vaccine’s effectiveness because it included members of communities that have been hit the hardest by the pandemic.

Michael Osterholm, the director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, said minority populations are at a greater risk for COVID-19 in part because of their socioeconomic status and because many members of those communities are essential workers.

“It could be huge to reduce the number of cases of COVID-19 not only in terms of reducing the illness in communities but giving the communities confidence that they can try to find that new normal in life,” Osterholm said.

Osterholm said the rate at which vaccines are being produced will likely not continue when the pandemic ends. He said making a vaccine at this speed is more expensive than going through the five-to-seven year process it typically takes and the government is unlikely to fund those efforts when there is not an imminent crisis.

“I think at this point it’s a situation where the people, the government is willing to spend that additional money to do this kind of work, which is very expensive,” he said. “In that regard, that’s not going to happen unless you have a crisis.”

Anna Wald, the head of the allergy and infectious diseases division at the University of Washington School of Medicine, said including a diverse group of participants in the trials will increase trust in the vaccine among members of those populations.

“COVID-19, for a variety of reasons, has affected the people of color and minority populations clearly disproportionately, and aside from the fact of why that is, it is clear that those are the people that we have to protect, that we have the obligation to protect most of all,” Wald said.

David Benkesser, an assistant professor of biostatistics and bioinformatics at Emory University, said the way COVID-19 vaccines are being evaluated is “standard” even though the process is accelerated.

“There’s a lot of uncertainties about what the impact will be that depend on the details of the results of these trials,” Benkesser said. “But if I had to bet, I would put my money on there being at least one vaccine that is efficacious but probably not perfectly so.”