Experts in public health data said the University’s COVID-19 tracking dashboard will help students and officials make informed decisions about how to handle the pandemic.

The dashboard, which was released last week, will provide daily updates on the 4,000 on-campus community members who are required to be tested weekly, the dashboard’s website states. Officials said in a release that they hope the dashboard will “ensure transparency” as they start to discuss if and when students can return to campus.

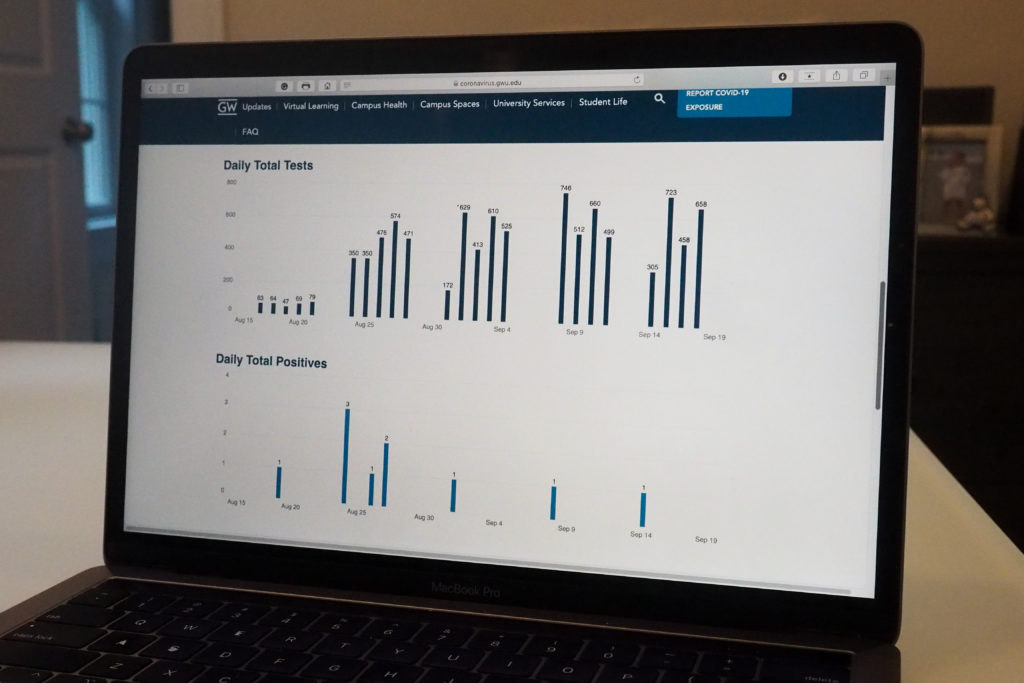

The dashboard uses interactive bar chart graphics to display daily total administered tests, daily total positives and seven-day positive rates as well as a breakdown into student and employee results, reason for getting tested and affiliated campus. Milken Institute School of Public Health researchers developed the University’s diagnostic tests, which will be processed in an on-campus public health lab, the website states.

“We are continuing to gather information about the current spread of the virus and projections about its trajectory – both in the D.C. region and nationally – and how these factors and any local government limitations will affect our operations next semester,” University President Thomas LeBlanc said in the release.

As of Sunday, the dashboard showed 10 positive cases after testing 9,453 community members.

Health experts said releasing COVID-19 data in an understandable way is crucial for officials to maintain trust between them and the community they’re guiding through the pandemic.

Kasisomayajula Viswanath, a professor of health communication at Harvard University, said college campuses should release testing data to promote informed decision-making on how to operate during the pandemic. He said the surrounding residents of a city college campus are an equally relevant audience for this data because they interact with students in their community.

Foggy Bottom community members voiced concerns last month that off-campus students’ return to the neighborhood could put Foggy Bottom’s elderly community at risk of contracting the virus. Some members of a fraternity also contracted the virus after attending an off-campus party earlier this month.

“It is essential for them to know how safe it is to enter the buildings, not enter the buildings, attend in our classes and not attend classes, open the restaurants and not open the restaurants,” Viswanath said. “All these decisions will depend upon the information they get.”

Viswanath said public health communication during emergencies depends on “three principles of transparency, trust and credibility.”

“We are demanding a lot of people in the COVID-19 context,” he said. “So if you want people to comply, they should be able to trust you and you should have the credibility. The open release of this data is a first step toward building that.”

With at least 88,000 positive COVID-19 cases across 1,600 college campuses, the GW dashboard joins the effort of many universities, like Boston and Syracuse universities, to distribute testing data to its community.

Rolf Halden, the director of the Center for Environmental Health Engineering at the Biodesign Institute of Arizona State University, said this type of public access to data is necessary to combat COVID-19 on a uniform, national level so citizens and government officials can make decisions about their COVID-19 strategy using the same basic information.

“Society is at a critical juncture,” Halden said. “We know how powerful data is, and we know and appreciate certain data is withheld from us for various reasons to control public opinion. But when it comes to our health and the health of our families and loved ones and the health of not only the country and its population but also the economy, I think everyone has a right to access this data.”

Halden said GW’s dashboard is a step in the right direction for the community because it shows transparency in the University’s handling of the pandemic and allows students and community members to make informed decisions as they navigate the pandemic.

“Obviously, it’s the first step and there could be more data on it, but it’s an important step because it signals that your community is willing to share data that is available, and that reflects the health status of your community,” he said.

Lia DeGroot contributed reporting.