Peyton Wilson, a junior majoring in political communication, is the Black Student Union’s executive vice president.

I’ve been exposed to images of black bodies being beaten, murdered and abused since I was 11 years old. You don’t know what it’s like to be a child knowing that just because of the color of your skin, your life is disposable. It didn’t matter why, it didn’t matter if you didn’t do anything wrong, you were black. In America, that’s a crime.

As long as I remember, the threat of interacting with police and the outcome it may have has influenced every decision I make. Black people live their whole lives looking over their shoulder, afraid to live their lives, constantly in fear that at any moment someone could identify them as a threat and their life can be over. The value of my life should not be in the hands of someone other than me, but black people don’t have that luxury.

Being born black in America is a death sentence. That’s not an exaggeration. That’s not an embellishment. In this country it doesn’t matter if you’re a lawyer, a Division 1 student-athlete, a teacher, a doctor or a doctorate — if you’re black, that’s what’s seen first. But why does a black person have to be successful to not be murdered by the police? I’m tired of seeing over and over the accomplishments and accolades of our brothers and sisters who were murdered to prove the wrongfulness of their death. Black people shouldn’t need a resume to put value on their lives. Considering the number of black bodies killed and abused at the hands of racists, I wonder how many people faced the same violence but were not fortunate enough to have someone nearby to record it. How many of us will never receive justice because we didn’t get public attention? Every day I hope that if I’m killed because of the color of my skin, that at least someone will be around to document it, because otherwise there’s no guarantee the killer(s) will face consequences and I will be another nameless black body lost at the hands of the violence our country perpetuates.

So I expect all non-black people, especially white people, to be willing to sacrifice some of their comfort to help your black brothers and sisters. As someone who goes to a school that prides itself on its liberal values, I don’t see enough people not just being anti-racist, but intolerant of racism. No one is rewarded for the bare minimum. As long as you protect the racist people in your life and do not speak up and condemn racism when it shows its face, you are a tool of white supremacy. We often condemn silence and allow an Instagram post to qualify as speaking up, but for me, posting on Instagram is silence until there is action behind it. Until you are willing to get uncomfortable, take risks and lay your life on the line like black people have done every day, your Instagram post means nothing to me. The real work happens without the gratification of social media. Are you willing to check your friends when they make racist jokes? Are you willing to confront the backdoor racism you encounter in white spaces? When you log off social media and move on about your life, you have your whiteness as a shield. My blackness makes me a target.

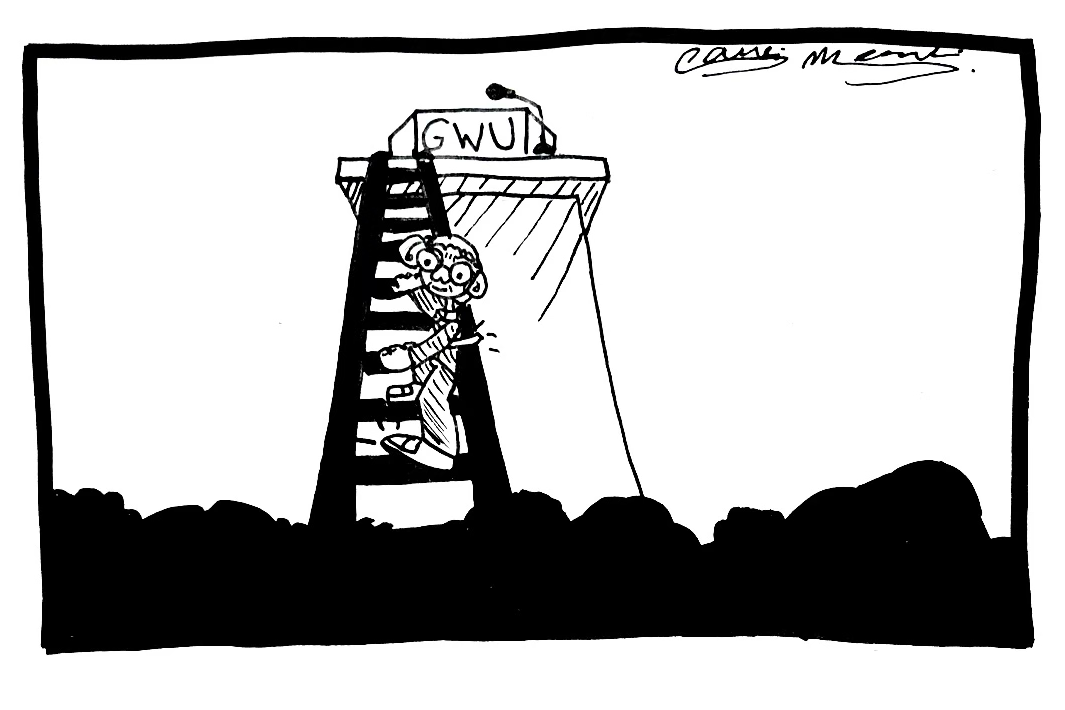

Part of being an ally is letting black people speak and have their time. Too often I see black injustices lumped together with other issues or diminished by saying “well other people experience this too.” It needs to stop. It’s possible to discuss the intersection of blackness with the struggles of other marginalized groups without completely shifting the narrative. Every time black people cry out for justice and institutional change, every other community is brought into the discussion. Struggles of other communities are results of the same white supremacist systems that have harmed black people for centuries, and they must receive justice for the harm done to their people. But black people are always expected to share their struggle. We consistently put our needs and struggles on the back burner to uplift every other community and see them reap the benefits while we stay at square one. You can see this with the modern feminist movement which was taken from black feminists and the queer rights movement commandeered from black queer activists at Stonewall. White voices have dominated black issues for too long. Let us speak.

Every day I’m scared. Every time my dad leaves on a trip for work, I pray so hard that he comes back I cry. Every time I go out with my friends we need to remember to act “composed” because a group of black people walking down 22nd Street at 10 p.m. could be seen as disruptive and threatening. I’m too scared to skate too early in the morning or too late at night because I don’t want someone to call the police on me and question if I live in my neighborhood. If I wear my hood, “she looks like a suspect.” If I keep my hands in my pockets, “I thought she had a weapon.” If I spend too long in a store, “But officer I thought she was stealing.” If I go on a walk at night, “She looked really suspicious.” I can’t live my life without being in fear, because as long as you’re black, nothing you say or do matters as long as you look the part. And you always look the part.

I’m tired of living like this. I’m tired of seeing my friends and loved ones in distress and being traumatized over and over every time we go on social media. I refuse to let my blackness be a death sentence. The only way to make amends is not reparations nor having more black police officers. A system that was not designed with us in mind cannot protect or serve us. It will take the dismantling of systems of white supremacy that continue to allow and encourage black violence. We owe it to ourselves and our ancestors to use our fatigue and exhaustion as fuel for the fight. Make time to heal, make time to care for one another — but be ready to engage in the fight.

I’m calling on non-black people, allies and those on the fence to get comfortable with being uncomfortable. Until you are ready to go beyond posting on social media and address racism in your personal relationships and private spaces, we will never find justice. Your closed-door conversations and jokes affect our daily lives. You owe it to the black students at this University and the black people in this country to do better.

Want to respond to this piece? Submit a letter to the editor.