Ivy Ken is an associate professor of sociology.

University President Thomas LeBlanc informed the GW community that as we move toward a new academic year, we need to prepare for “pay or benefit reductions, early retirement options, furloughs or layoffs,” among other cost-cutting actions. The announcement has created deep unease among staff and faculty, who are already working overtime to meet the new demands brought on by the pandemic.

As we all work to figure out how to continue the University’s mission of creating and sharing knowledge, the obvious solution so far has been to hold classes online. GW is not unique in this – it is happening all over the world. We live at a time when the technological infrastructure that allows classes to go online – from the internet, itself, to the availability of computers, software and technical support – is as strong as the magnified demand for it during social distancing.

But the rationale for holding classes online is absent. As online learning has ramped up in colleges and universities over the last two decades, education researchers have identified best practices for online learning success. It is an understatement to say that the practices and conditions under which faculty and students are being asked to turn everything over to Webex and Blackboard right now are far from ideal. Faculty largely do not have the training. One of my students in the spring semester told me about a business professor who couldn’t figure out the technology, so he simply lectured his students for an hour at a time over the phone. I feel that my “magic” as an instructor happens in the classroom, where I engage with students face-to-face, read their nonverbal cues, respond to their ideas and help them struggle collectively with the material. I cannot reproduce this online, and my students will suffer.

In the 19 years I have been at GW, class sizes have increasingly gotten bigger. My 35-student theory course got bumped up to 45 and raised again to 50, with no additional support. No student at GW who has been cramped into a tiny classroom will be surprised that these 50 students must still meet in the rooms designed for 35. To the extent that higher class sizes reflect increased demand for sociological theory, this is a great thing. But this is not what it reflects. It is one small example of a university that is trying to do more with less. GW wants a smaller numbers of professors to teach a larger numbers of students.

Again, GW is not unique in this. The trend in higher education has been to employ the techniques developed by profit-seeking corporations to – as the chair of the Board of Trustees recently put it – cut the “fat” from University budgets. Professors, apparently, are the unnecessary “fat.”

A much better solution, albeit one that would require enough courage to buck the existing trend, is a hiring binge. Not a hiring freeze.

A hiring binge would allow more professors to handle smaller classes that could possibly meet in person in large rooms. Anthony Fauci, a leader on the White House Coronavirus Task Force, recently advised that it would be possible for universities to welcome students back in the fall, if all were tested regularly and modifications were made to residence halls and classrooms. This means all those classrooms at GW that were designed for 35 students, into which dozens more students have been packed, need to become classrooms of 10. My 60-student fall semester class, for instance, could be turned into three different 20-student classes with three different instructors who each meet with 10 students at a time. This would increase the workload of any one instructor, who would need to meet twice as often with smaller numbers of students. But that sort of workload increase would be better than requiring professors to hastily – and probably poorly – conduct robust, meaningful online class sessions.

We need more people, not more technology. Ideally, this need could spark something like a federal works program that would hire masses of underemployed doctoral students into tenure-track jobs so we could handle this crisis in a way that is both humane and pedagogically sound. It should go without saying – but doesn’t – that these positions should absolutely be tenure-track, since these positions are the only ones to guard against the sort of layoffs that GW and other schools have threatened and implemented.

I realize that implementing this at GW would be an enormous task. Perhaps one source of support for an initiative like this would be not the federal government but the D.C. city government. Mayor Muriel Bowser and city council have often devoted serious amounts of money to progressive ideas like healthy meals for K-12 students and the bike lanes. The consortium of D.C. colleges and universities could jointly request the city’s support and make the District a leader on this issue. Some may feel that public tax dollars should not be spent on private university professors, and in general I agree. But this is a solution meant to prioritize students. In exchange for public money, perhaps our universities could commit to enrolling a much higher proportion of D.C. students.

What is important is to fight against the tide of bigger, online classes, which just do not serve our students or our communities well. The current crisis presents an opportunity to move away from the pedagogically bankrupt focus on efficiency and toward solutions that are best for the people and communities we serve.

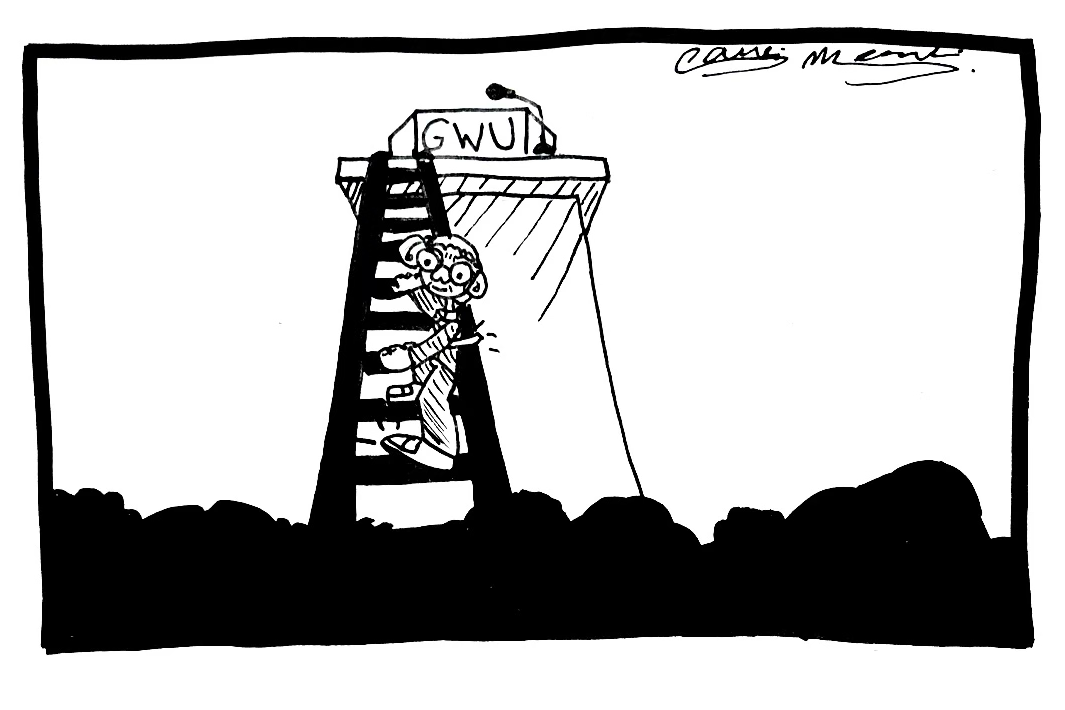

The Board chair recently said in an email that trustees are “directing the administration to explore and consider all appropriate options. A sense of urgency is warranted and the status quo is not an option.” I share this sense of urgency and hope the Board, administration and city will consider halting the freeze and engaging in a hiring binge to benefit our students.

Want to respond to this piece? Submit a letter to the editor.