History courses often delve into delicate stories of pain and trauma involving cultures from around the world. Discussing sensitive topics like colonialism and slavery affects students – particularly those of color – and the professors who teach them should have a keen understanding of how to approach those conversations with care.

I have taken three history courses that deal with the history of people of color: Freedom Struggles in Black and Brown, Slavery, Segregation and GWU and Modern South Asian History. These classes were taught by white, male professors who had the best intentions but could not cover the issues as comprehensively as someone with a personal relation to each topic could. History is not a subject removed from current events – segregation and colonial conquests around the world affect poverty rates and judicial injustice for many minorities in the U.S. and beyond. Administrators should make an effort to find professors of color who could teach classes that concentrate on minority cultures, specifically historians who are from or identify with the history of the country or region they are teaching.

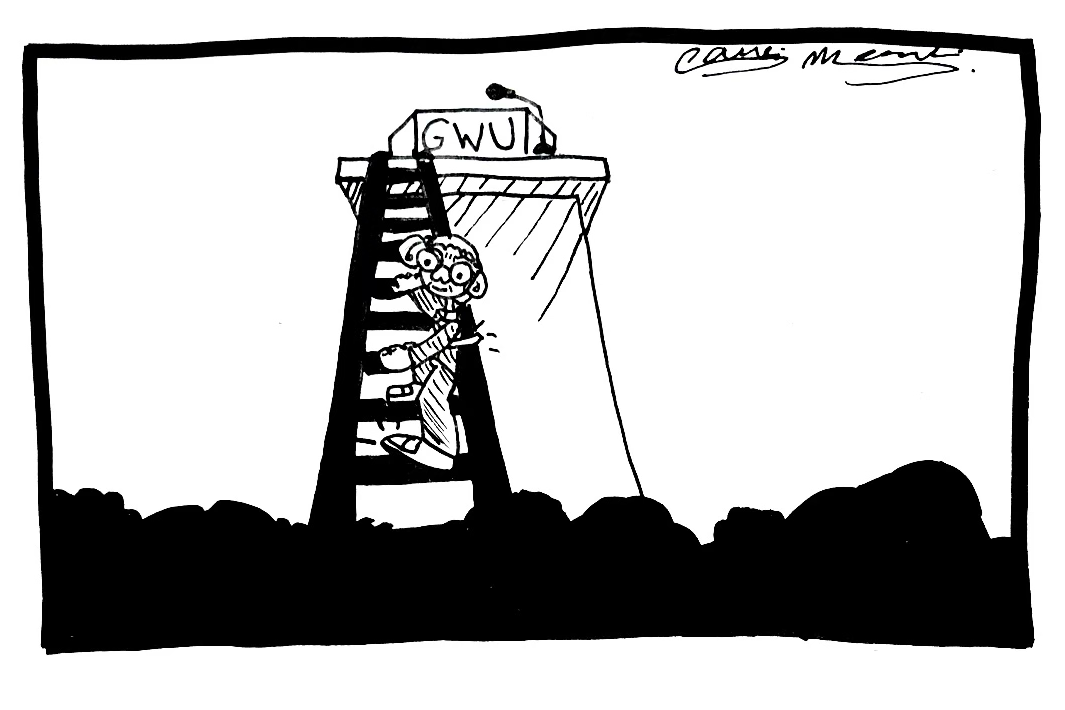

Professors who lack a connection to a history subject often hesitate to speak candidly about controversial issues like U.S. race relations. In the Freedom Struggles in Black and Brown class, the professor – though knowledgeable in the history of the civil rights movement – did not acknowledge his own race in a history course that has everything to do with the color of one’s skin. Recognizing his own limitations in discussing the topic could have made more students comfortable to speak in class.

In Modern South Asian History, the professor would ask our class to think about the events that led to the partition of India into India and Pakistan. A large part of our grade was based on a mock trial in which mostly Indian politicians and non-political freedom fighters were pitted against one another, while the professor acted as a judge to decide which side would be deemed “guilty” for the partition of India. The activity irked those of South Asian heritage in the class. Although multiple Indian political players played a role in the partition, the activity focused more on exploring their failures than the exploitation and manipulation of the British Raj at the time. The professor’s blindspot was understandable but had a lasting effect on some students in the class.

Many of our assignments in the class were based off of scholarship produced by the “Cambridge” school, mainly British or British-educated scholars, rather than the “Subaltern” school, mainly South Asian or South Asian-educated scholars. Much of our curriculum was shaped by British scholars analyzing India as opposed to Indian scholars analyzing their own history. This difference in literature undoubtedly affects students’ perceptions of which countries were to blame for major historic upheavals like the partition of India.

The correct pronunciation of names and places is a baseline necessity in receiving and providing an acceptable history education. In South Asian history, the professor would repeatedly mispronounce the names of political figures like Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, the founder of a right-wing Hindu party, and the Marathas, a line of kings whose empire took over after the Mughals.

There were too many names that the professor mispronounced, rendering those of us who did know the correct pronunciation silent because we did not want to disrupt the discussion. Instead, the most we could do was make sure our pronunciation remained clear and correct. The professor did not make any efforts to rethink his own pronunciation.

Some students who use different names for the convenience of their peers and professors have argued that mispronouncing their student’s name can undermine their self-worth or invalidate their ethnic identity. The case is similar for the pronunciation of a particular culture. In South Asian history, every time the professor did not make an attempt to pronounce a particular historical figure’s name correctly, he passed on the wrong pronunciation to nearly 20 students.

It is possible for professors who are not minorities to capture the appropriate understanding necessary to teach these classes. But doing so requires acknowledging how their own race serves as a shortcoming in their understanding of the material, something that was never addressed in the classes I have taken. While the professors’ unconscious biases may still impact their perspectives, making the class aware of those potential biases could limit the effects.

Administrators must hire professors of color to teach classes that deal with minority cultures. Otherwise, these courses will not give students – those of color and those who are not – a well-rounded and productive understanding of different regions and different people.

Shreeya Aranake, a sophomore majoring in history, is an opinions writer.