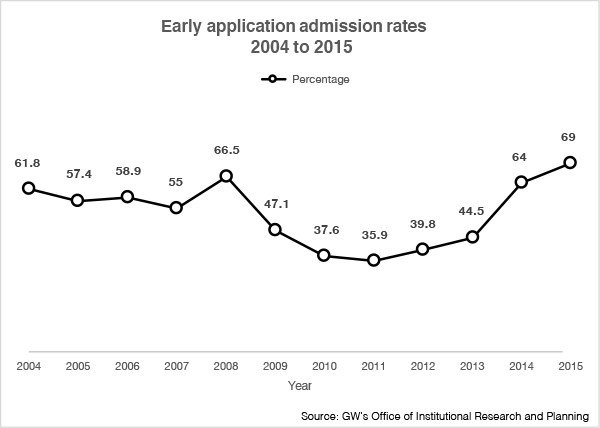

The University admitted 69 percent of applicants who applied early decision last fall.

That percentage is the highest percentage of early decision applicants admitted at any time in the last 10 years, and brings GW a group of students who are practically guaranteed to enroll. That certainty is important because as students apply to longer lists of schools, colleges can struggle to predict who will enroll.

GW admitted 714 of the 1,034 students who applied early decision, an amount that has almost doubled since 2011, when 36 percent of applicants were accepted.

The number also reflects a drop in early admission applications. The last two years, GW has received about half of the early decision applications it normally brings in, according to the Office of Institutional Research and Planning.

But even with the increasing early decision acceptance rate, the majority of students still come to GW through the regular decision application. About 8 percent of this fall’s freshman class were early decision applicants, according to the Office of Institutional Research and Planning.

Senior Associate Provost for Enrollment Management Laurie Koehler declined to say whether she expects the acceptance rate for early decision students to increase again. She said applying early decision makes sense for applicants who know GW is the “best fit for them.”

“Our goal is to enroll the most academically talented, diverse class we can each year. We absolutely want to enroll the best students from around the country and the world as we increase the academic quality of the class,” Koehler said.

Last year, Koehler attributed a 20-point drop in early application selectivity to a strategy to enroll academically stronger candidates.

Students who apply early decision submit a non-refundable enrollment fee and withdraw all applications from other institutions. Koehler said students who apply to GW have “very high” yield rates, meaning a high percentage of them will accept their admissions offers.

“Once our early decision students have been accepted it provides us with a framework for how many students through the regular decision process we need to admit to meet our target enrollment goals,” Koehler said.

Schools need to accurately predict the size of their classes to ensure they hit revenue targets. A larger-than-expected class size would help a school’s bottom line but could also put a strain on student services, or mean there are fewer spaces for students in classes and residence halls.

GW admitted 45 percent of applicants to the Class of 2019, the highest acceptance rate in a decade. Officials said that increase was in response to budgetary pressures: They hoped to grow overall enrollment after two years of missed budget projections.

In September, GW fell three spots in national rankings and the report’s author attributed the slip to relative drops in student graduation, retention and selectivity rates.

Koehler said that while the Office of Admissions is “cognizant” of how rankings and admission rates are factors prospective students consider when applying to college, admissions officers at GW are focused on recruiting an academically strong class.

In October, Koehler had said that the Class of 2019’s GPA was nearly one-tenth of a point higher than classes in the last five years, which she called the “best indicator of the academic strength of our students.”

Robert Chernak, the former vice president for Student and Academic Support Services, said the “rule of thumb” for admissions offices is to bring in about one-third of a class through early decision enrollment.

He added that admissions offices are more likely to admit early decision students who apply to less popular programs, like the School of Engineering and Applied Science, than those who apply to the programs GW is best known for, like the School of Media and Public Affairs.

“Let’s say you had a lot of students apply early for engineering, and undergraduate enrollment in engineering has been stagnant, then that would be one reason to accept as many early decision engineering candidates as you could, as opposed to SMPA, where you know even in regular decision you’re going to get more than sufficient applicants,” he said.

Sandy Baum, a professor of higher education finance and policy in the Graduate School of Education and Human Development, said bringing in a larger percentage of early decision students benefits institutions because it indicates that students will stay at the school.

“They’re not so worried about them applying to six other schools,” Baum said.

In August, University President Steven Knapp said he will center this year around increasing the University’s retention rate, or the number of students who remain at and graduate from GW, a goal that could be boosted by early decision applicants who arrive knowing GW is the school for them.

Daniel Klasik, an assistant professor in the Graduate School of Education and Human Development, said low-income students may avoid applying to institutions early, which could widen the socioeconomic gap on campuses that rely heavily on early admission applicants to fill their freshman classes.

“It’s a policy that tends to benefit wealthier students. Low-income students don’t often have the information or the preparation to have their applications together in time,” Klasik said.

Koehler said GW is “very sensitive” to making sure early decision applicants are told about their financial aid packages early. If an early decision applicant is not able to afford GW with the package they receive, they are released from their contract, Koehler said.

GW has expanded its opportunities for low-income or minority students to attend the University in recent months, including adopting a test-optional admissions policy and partnering with groups like the Posse Foundation, which will bring students from Atlanta in groups of 10 to GW.