When I came to GW, I didn’t sign up to be a spokesperson for India. But in many of my classes, I have been in a position where I am one of few Indian students and have felt a responsibility to correct professors and students who mischaracterize Indian culture or present inaccuracies about Indian politics in class.

During my Introduction to Comparative Politics class last semester, we often discussed political change in foreign countries. The professor provided India as an example because at the time, the Indian Supreme Court had just struck down a ban on gay sex. However, instead of accurately stating this information, he said India had just legalized gay marriage – but that was not true.

As the class discussed the topic, students continued to cite the professor’s example. The discussion only lasted for a couple minutes and the class moved on to a different topic.

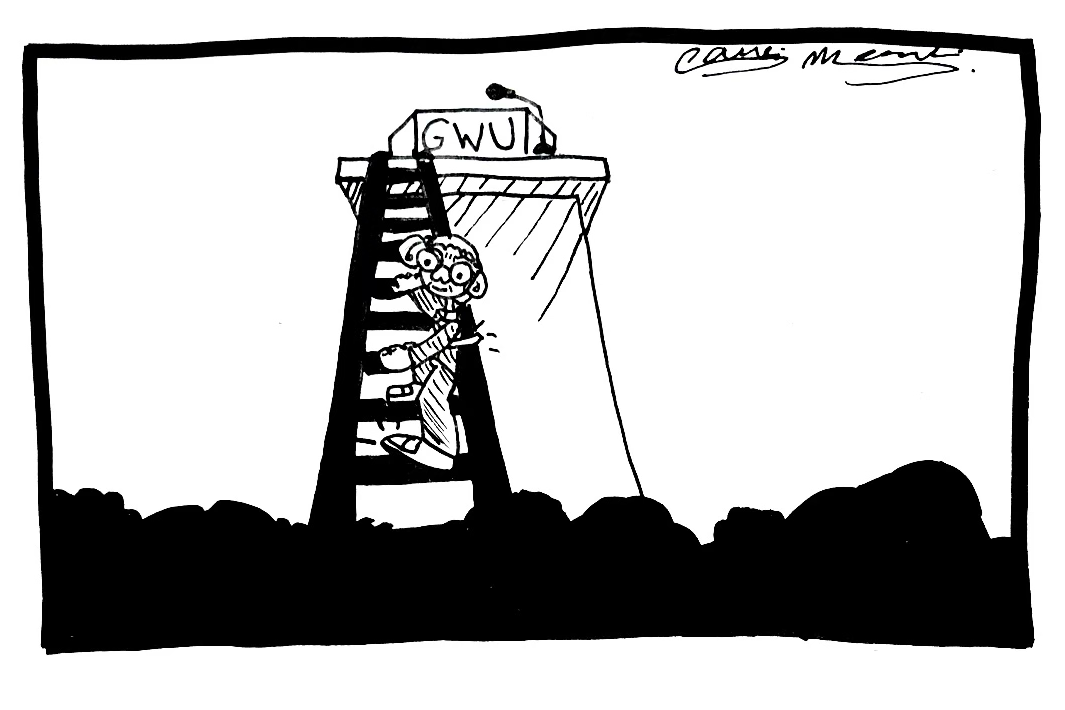

When the professor made the mistake, I felt a sudden need to correct him but I was stopped by the fear of being seen as the “Indian kid” who is always piping up to defend her country regardless of whether the topic is relevant to the class or not.

After the professor’s false statement, I looked around and waited to see if anyone had noticed the error and was willing to raise their hand to correct the professor. I weighed the importance of my peers’ judgment versus the responsibility I felt as someone of Indian descent to clarify the professor’s inaccuracy. Ultimately, I decided not to raise my hand.

But whether a student in my position corrects the professor is not the point. No one should feel obligated to represent an entire country or culture due to someone else’s ignorance. The feeling of obligation is an undue burden on one individual. It also perpetuates the notion that students of a specific background should speak on behalf of a country that represents only a part of their identity.

The undergraduate population last fall was the most diverse in at least a decade, with 10.8 percent of the student body identifying as Asian, while 10.3 percent and about 7 percent of the population identify as Hispanic and black, respectively.

It is imperative that both the student body as well as faculty members are aware of these. This is not a problem that can necessarily be fixed by diversity trainings or online tutorials.

Overall a more diverse student body and an awareness among faculty to be aware of their information about non-Western countries will alleviate this burden. As long as there is a small portion of students who are members of minority communities, there will be a larger burden on each of them to represent their respective countries and identities. While that issue cannot be solved quickly, acknowledgment from professors about their limitations will make classrooms a more welcoming place.

Shreeya Aranake, a freshman majoring in political science, is a Hatchet opinions writer.

Want to respond to this piece? Submit a letter to the editor.