Old college yearbook photos depicting individuals wearing blackface sparked a national conversation about racism on college campuses. Earlier this month, an old yearbook photo of Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam surfaced featuring one individual in blackface posing with a man in a Ku Klux Klan hood.

Shortly after the scandal broke, colleges across the country began to examine their own ties to racism. The Hatchet investigated GW’s old yearbooks and uncovered dozens of photos of former students in blackface, KKK hoods and other racist outfits in Cherry Tree yearbooks.

Stories like this have popped up at many universities, and all show that racism has a long history on college campuses. While the fact that racism was present on campuses in the past is likely not surprising, these examples are particularly alarming at a time when universities are becoming more diverse and blatant discrimination against minority communities has decreased.

Universities like GW have come a long way from openly racist and discriminatory practices, but institutional racism can be seen in the history of many schools across the country. It is troubling that GW’s history is laced with racism and discrimination, but we must recognize it to move forward.

There is no evidence that the University, formerly called Columbian College, owned slaves. But individuals connected to GW owned slaves and faculty and students benefited and profited from slave labor.

In the years following the abolition of slavery, GW still had blatant racism on campus in the form of blackface and segregation. When Lisner Auditorium opened in 1946, it was a segregated theater, which eventually sparked protests on campus and forced the Board of Trustees to desegregate the auditorium. And prior to desegregation in 1954, the law school and medical school only allowed black students to take night classes.

Three years later, the University officially desegregated, but restricted housing to just white students until the early 1960s. The desegregation process was delayed by former University President Cloyd Heck Marvin, who pushed back against allowing minorities and African Americans on campus.

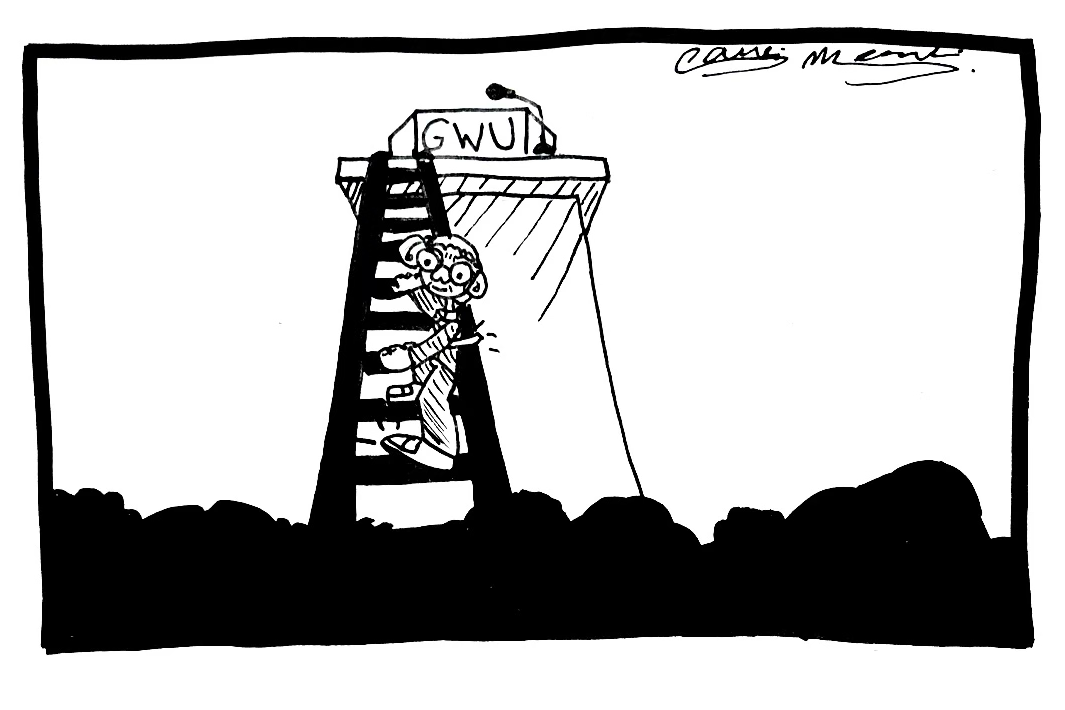

Every day students work, hold events and spend their free time in a student center named after Marvin who openly opposed desegregation efforts, fired individuals who supported desegregation and created discriminatory policies against African American students by only allowing them to register for night courses. Despite pushes from students and faculty to rename the Marvin Center, the University continues to honor a racist.

During the time that GW was segregated, and even once the University became desegregated, students took part in discriminatory and offensive activities. Photos from the GW Cherry Tree Yearbook displayed at least 14 times students wore blackface and three instances of students donning KKK hoods spanning from 1914 to 1977. These images, some of which are from after the peak of the civil rights movement, prove that racist expressions were previously normalized.

GW is not the only university to have racism in its history books, but other institutions have taken action to change how their narrative ends. Peer institutions like Georgetown University renamed two of their buildings to honor and respect the African Americans they sold and oppressed in the 1800s. While changing building names is a strong first step that the University should take, Georgetown University also began offering legacy status admission to students who are related to the Maryland Jesuit-owned slaves.

Given the enduring nature of racism on campus, it is no surprise that blatant racism continues at GW. Last year, a student in a sorority posted a Snapchat depicting two other students with a racist caption. While this single incident gained national attention and sparked changes including mandatory diversity training and a new director for diversity and inclusion education, it is clear racism still persists and this example is one of many students of color face on campus every day.

Students and faculty have been vocal about the need for a change in GW’s culture surrounding race and diversity. The longing for change can be seen in how students came together in several town hall meetings to discuss race and diversity on campus after the racist Snapchat post circulated.

While active racist incidents on campus are shocking for some and unsurprising for others, what is particularly troubling is to see how students responded to incidents from about a century ago but fail to respond when students are discriminated against on campus today.

GW’s history of racism that recently came to light in old yearbook photos shows how majority white institutions struggle to come to terms with their racist pasts. The past is ugly and hard to swallow, but students can reverse GW’s racist legacy by recognizing the institution’s past and insisting that we do better than the students who came before us.

Hannah Thacker, a freshman majoring in political communication, is a Hatchet opinions writer.

Want to respond to this piece? Submit a letter to the editor.