For the second year in a row, three senior administrators have announced their departures in one month.

A top finance official, the medical school dean and an alumni relations leader all announced their resignations this month following a year of eight other administrative departures. Experts said administrative turnover at a high level can make faculty and staff unsure of the overall mission of a university, negatively affecting how comfortable they are in their jobs.

University spokeswoman Lindsay Hamilton said each of the three January resignations reflected personal decisions, and employees make these choices for a “variety of reasons.”

“Employee transitions are a regular part of any large organization,” she said.

She declined to say how three administrators announcing their resignation in one month affects the University. She also declined to say what kinds of leaders the administration is looking for as replacements and how multiple ongoing executive searches would affect the University.

The University last had three top administrators depart in one month last academic year, when the vice president for research, the dean of the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences, the associate dean of students announced their resignations in March.

In total, eight major administrators left the University last academic year, while officials also hired a handful of top officials, including the vice president of development and alumni relations and the chief financial officer.

Kristen Ren, a professor of higher lifelong education at Michigan State University, said the first years after a new president arrives are an adjustment period for officials to discover how they work within the new administration and if they will be able to work under new division heads. University President Thomas LeBlanc entered his role in August 2017.

“Often, it is that within a few years, senior administrators the senior people will either jump on board with the vision of the new president or realize that it is not a good fit for them and use that as a time pursue a career somewhere else,” she said.

Though administrative turnover is often part of the job, Ren said that rapid departures can scare away fellow officials and even potential university donors because employees prefer a more “stable” environment.

“Because turnover brings so much uncertainty, people get nervous about their jobs they don’t know what direction to follow, so rapid turnover is not good,” she said. “For a place like GW where there are so many great colleges in the region, you can lose a lot of great administrators who go someplace more stable.”

Teboho Moja, a clinical professor of higher education at New York University, said organizations with a new leader can experience immediate administrative shifts, which does not become a problem until the departures trickle down to leaders past the president’s inner circle.

Administrators lower than the senior-most level have institutional knowledge about their office and GW that is valuable to a new president’s mission, she said.

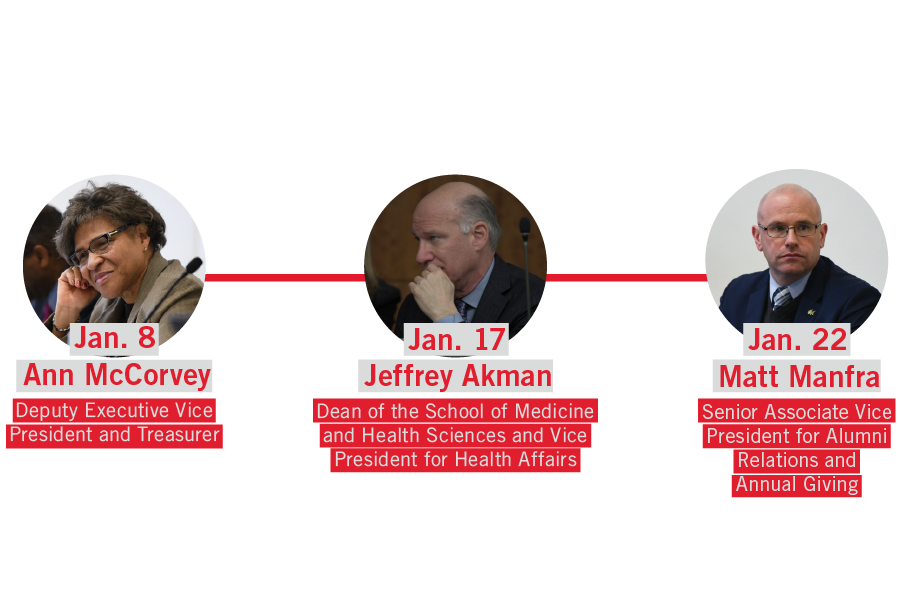

Two of the three administrators who left in January – Ann McCorvey, the deputy executive vice president and treasurer, and Matt Manfra, the senior associate vice president for development and alumni relations – did not report directly to the president. Jeffrey Akman, the dean of the medical school, reported to LeBlanc in the capacity of his role as vice president for health affairs.

Moja said that if administrators do not believe in the president’s vision for a university or feel they are not being listened to, it can be difficult for them to stay. LeBlanc has been pushing for a major shift in institutional culture since he arrived at GW and issued a culture assessment to faculty and staff last semester. LeBlanc put together a team of administrators last spring to focus on tackling the issue.

“I envision a case where the president comes in with sort of a preconceived vision of where the institution should be, and that vision is non-negotiable and they will carry on with it,” she said.

Moja said that if the University is trying to meet new goals and make big changes – like the culture shifts that LeBlanc has pushed for – personnel turnover will not help.

“I would not label it as bad but as challenging for the institution to operate and really find its feet and be able to operate and to make change,” she said.

Nathan Harris, an assistant professor of educational leadership at the University of Rochester, said higher education can be “conservative” with changing its leaders, and fresh vacancies offer an opportunity for fresh perspectives.

“When senior roles are filled with new people, especially people from different institutions, they bring different ways of doing things and different ways of thinking about problems,” he said in an email. “So while turnover among senior ranks can create some headaches it also creates opportunities.”

He added that losing top administrators can mean that the University is losing the valuable connections they had with people outside the University, like alumni or donors.

“That loss of institutional DNA, if you will, can be a challenge when senior people leave,” he said in an email.

Jessica Baskerville contributed reporting.