Following a nationwide trend, international student enrollment dropped this fall for the first time in at least nine years.

About 200 fewer international students are attending GW this fall than they did last year, the first decline since at least 2009 and the second year that the percentage of international students as a share of total enrollment has dipped. International higher education experts said the decrease is not a fault on the University’s international recruitment efforts, but falls in line with a nationwide trend of universities struggling to attract international students since President Donald Trump took office.

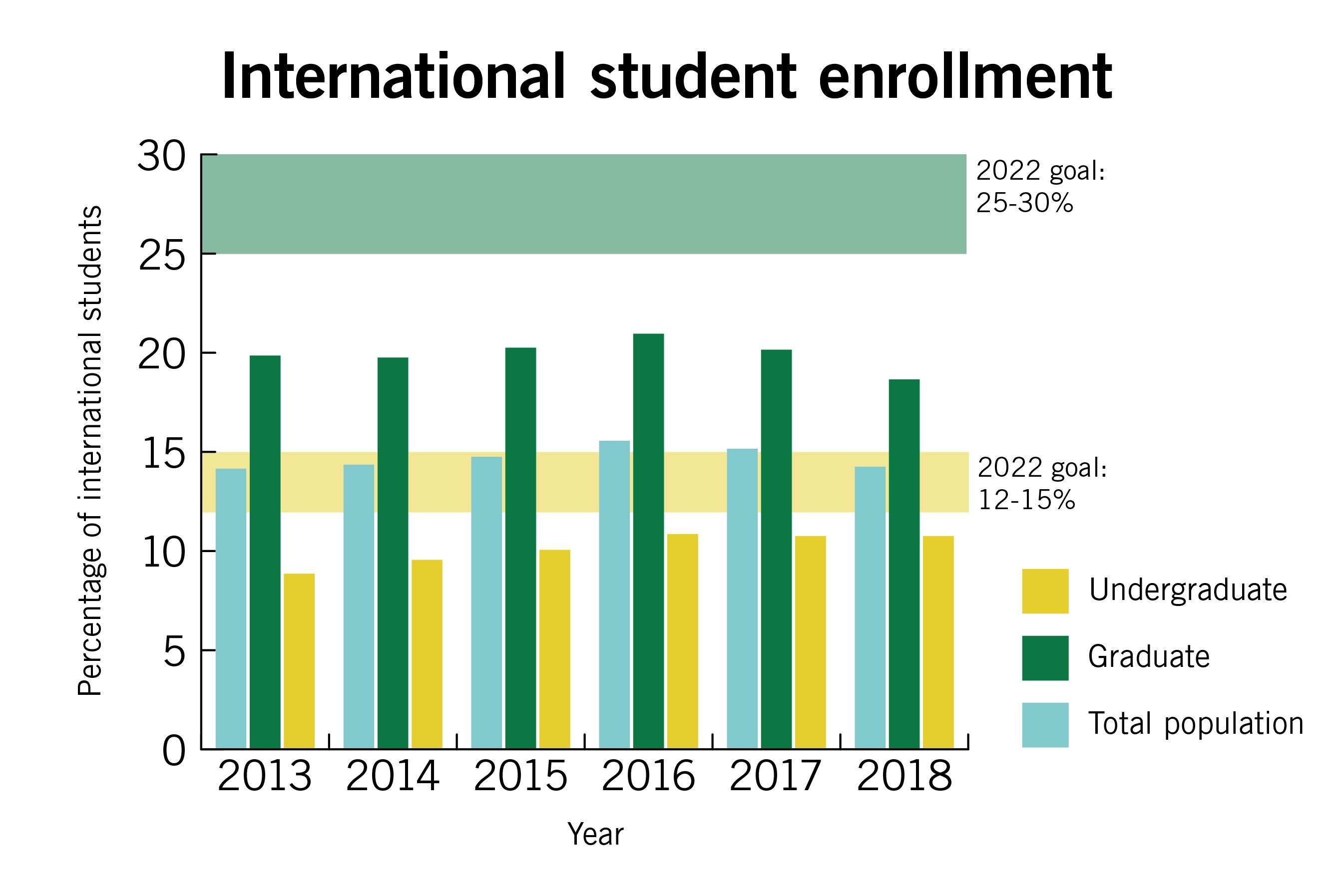

Roughly 4,000 international students attend the University this fall, making up about 14.2 percent of the population, down from 15.1 percent last year. The drop is the second consecutive year that the proportion of international students has fallen, though the total number of international students increased slightly between 2016 and 2017.

Olivia Columbus | Hatchet Designer

Source: Institutional data

The decline marks another setback for the University as it pursues a goal of increasing the international population to 12 to 15 percent of the undergraduate student body and 25 to 30 percent of the graduate student body by 2022.

Provost Forrest Maltzman said that despite the fall, the University is still on track to reach its international student goal. He said the University is “slightly below the goal overall” for undergraduates and “in that range” for graduates.

About 11 percent of the current undergraduate student body is comprised of international students – the same as the year before and about 4 percent less than officials’ goal. International graduate student enrollment fell from about 20 percent in 2017 to 18.6 percent this academic year, about 10 points short of officials’ goal, according to institutional data.

“If you look at GW, our international enrollment since we adopted that plan has really increased and as a result of that, we are a much healthier institution,” Maltzman said.

He added that the drop will not affect the University’s finances, and GW is “well within our tuition budget.” International students typically pay full tuition, funneling money into the University’s budget, which is 75 percent tuition-reliant.

“We set goals every year, we have net revenue goals and we seem to be revenue track for meeting our revenue goals as an institution,” Maltzman said.

He said officials continue to work on improving international student enrollment numbers and diversifying the number of countries international students hail from.

A group of officials and faculty said last fall that while the University has continued to improve its international student enrollment, the population is not as “geographically diversified as hoped.” The group reported in a self-study that too much growth has been centralized in China, India and South Korea, where officials have honed recruitment efforts in recent years.

Between 2017 and 2018, the number of international students coming from the top three countries fell by about 150 students, though students from China, India and South Korea continue to comprise nearly two-thirds of GW’s international student population, according to institutional data.

Adina Lav, the assistant provost for international enrollment, said officials have made “tremendous strides” in improving the diversity of its international student makeup and encouraging “a more inclusive and thoughtful environment on campus.”

“As national and international political and economic conditions change, we will continue to work collaboratively and strategically to ensure a strong representation of diverse international students at GW,” Lav said in an email.

She declined to say what strategies officials are employing to recruit international students from multiple countries, how the self-study played a role in creating those strategies and who contributed to the strategies.

Experts said the decrease is a lingering effect of international students’ perception of the United States since Trump took office. Nationwide, the percentage of international students enrolled at U.S. institutions has dipped by 6.6 percent over the past two academic years, according to OpenDoors data from the Institute of International Education.

Krishna Bista, an associate professor at Morgan State University in Baltimore who has written about international students in higher education, said the fall fits into a nationwide trend of universities failing to recruit international students under the Trump administration. The trend especially affects those from China threatened by a visa restriction or Middle Eastern students impacted by a travel ban issued by the president, he said.

“I would definitely blame the national policy, the way the Trump administration has looked into immigrant populations, including negative connotations with many of these Middle East or Chinese students,” Bista said.

But Bista said doubling international student enrollment by 2022 is still “promising” because GW’s urban setting is one of the “prime locations for immigrant students,” and the University gears scholarships and services toward aiding international students. The University added a scholarship for international students in September and launched an airport welcome program in May to greet international students when they arrive in the United States.

“As long as the institution has support from the faculty and the office of international programs to include the students, I’m optimistic that GW will have that goal,” he said.

Chris Glass, an associate professor at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va. who has taught classes on international higher education administration, said international student enrollment could have fallen because the United States “is increasingly seen as having more complex visa processes.”

Nationally, the State Department has granted 13 percent fewer visitor visas over the past year, POLITICO reported.

He added that international students often lack career opportunities in the states after they graduate, making the possibility of studying in the country “less attractive.”

He said the University could use faculty and students to build connections with other institutions abroad and focus on its resources in career services so international students understand what opportunities they have to work in the United States.

“Most of the falling is because of things that are outside the University’s control,” Glass said. “My guess is what it’s going to need is looking to build new kinds of relationships and pipelines with new partnerships.”

Cayla Harris, Lizzie Mintz and Lauren Peller contributed reporting.