Reports of sexual violence on campus have more than doubled over the past three years – an uptick officials attributed to students feeling more comfortable reporting incidents to campus authorities.

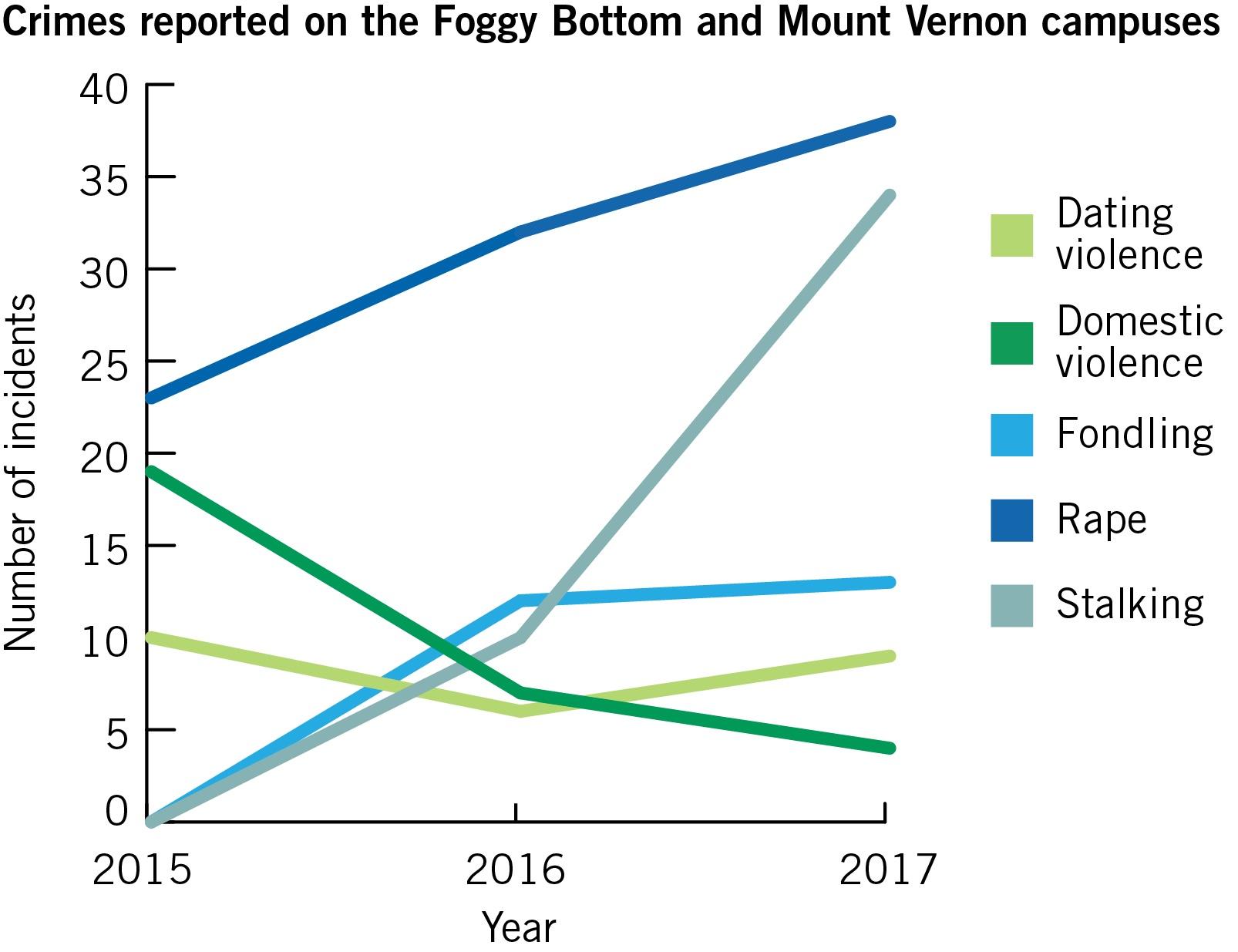

Thirty-eight incidents of rape and 13 incidents of fondling were reported on both the Foggy Bottom and Mount Vernon campuses last year, compared to 23 and zero in 2015, respectively, according to GW’s annual security report released Friday. Darrell Darnell, the senior associate vice president for safety and security, said the increase coincides with improved resources for survivors on campus and the international #MeToo movement encouraging survivors to tell their stories.

“People are more aware of it and more conscious of it,” he said. “They think our country, rightly so, has moved to a point where we’re not swiping this under the rug all the time.”

Darnell said the University has instituted several new measures over the past few years improving the environment for sexual assault survivors to bring forward their experiences to faculty and staff, who can then relay information to the GW Police Department. He said Haven – a website launched in 2013 to provide educational materials about the University’s sexual assault policies – has helped students better understand the resources available to them. He said the Colonial Health Center and the University’s partnerships with D.C.-area support services have also helped students deal with their trauma.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: GW Annual Security Report

“It gives them the opportunity to get the assistance that they need – a support system that’s more geared to deal with these types of situations than a law enforcement official, while at the same time maintaining that option if they want to file a criminal complaint,” he said.

The increase comes amid heightened scrutiny about GW’s Title IX procedures. The Department of Education concluded a nearly yearlong federal investigation into the Title IX office in August after a student alleged that officials mishandled their sexual violence case. Several students have also sued the University or filed federal complaints over the past five years for alleged violations of Title IX laws.

The University overhauled its Title IX policy over the summer, mandating that all faculty report possible sexual violence incidents to the Title IX office and switching to a single-investigator model for all investigations into Title IX violations.

Darnell added that the #MeToo movement across the country is driving an increase in reporting sexual assaults because survivors are more encouraged that authorities will take serious action – either by offering support or acting on a criminal complaint – once the incidents are disclosed.

“People think, ‘What if I report this? Something’s going to happen,’” he said. “‘I’m not going to be stigmatized – I’m going to get the support that I need. If I want to file a criminal complaint, that complaint is going to get acted on. People are going to take me seriously.’”

While the number of reported incidents of sexual violence has steadily increased over the past three years, the number of similar incidents has fluctuated. Reports of stalking increased from zero incidents in 2015 to 34 in 2017, while counts of domestic violence fell from 19 to four over the same period.

Incidents of dating violence fell from 10 to nine between 2015 and 2017.

Campus security experts said sexual assaults are generally underreported on college campuses, so a spike in the number of reported incidents could signify that universities are creating a more welcoming culture for sexual assault survivors.

Aran Mull, the assistant chief of police for the University of New York at Albany, said the increase in reported sexual assaults may be indicative of a positive community atmosphere that encourages survivors to feel comfortable asking for help.

“We want to see that number go up,” he said. “It means your community is better at addressing it and better at creating a culture that allows them to come forward.”

Mull said many people prefer speaking with a Title IX officer or professor about their experiences instead of a police officer because students are often afraid that the police won’t take action if they report. He said resources for survivors outside a college campus are fairly limited because most people will have to choose between seeing a psychologist to address their trauma or being forced to go through the criminal justice system, which puts an increasingly high burden of proof on the accuser.

“The standard that they’re facing is beyond a reasonable doubt,” he said. “That’s profoundly difficult in many circumstances when we’re looking at a sexual assault case.”

Dana Perrin, the assistant director of public safety at the University of Rochester, said sexual assaults and sex-related crimes are the most underreported at universities because there is a “stigma” around reporting, despite recent efforts to increase outreach and educational resources nationwide.

“Anytime you can bring awareness, you may see a spike in your reporting,” he said. “If all it did was heighten people’s awareness, then you’re still getting better numbers.”

Anastasia Conley, Savita Govind and Andara Katong contributed reporting.