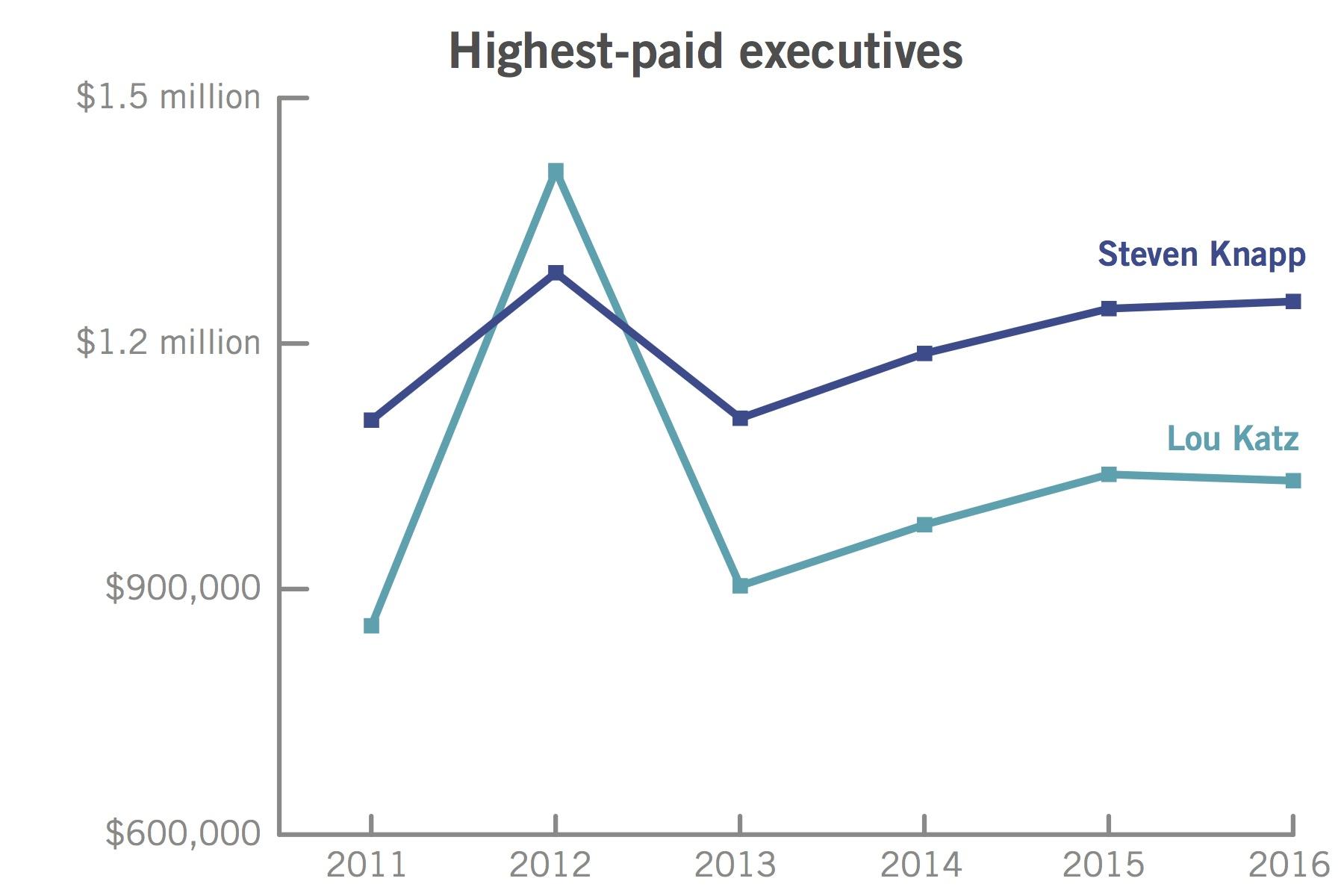

Four employees took home more than $1 million in calendar year 2016, according to tax documents.

The last time four of the highest-paid employees at the University earned more than $1 million in compensation was in 2012, according to tax documents. Higher education experts said increasing administrators’ salaries can help keep and recruit talented managers, but the public has questioned the ethics of giving officials raises in recent years as students take on thousands of dollars in loans to pay for their education.

Emily Recko | Graphics Editor

Source: GW’s 990 forms

Former University President Steven Knapp was the highest earner listed on the tax documents, with a compensation totaling more than $1.25 million. Both his base salary and additional compensation increased between 2015 and 2016, boosting his income by about $10,000 – a roughly 1 percent increase.

Knapp’s earnings dropped by 13 percent in 2013 before he received a 7 percent increase the next year. Though Knapp’s salary and bonuses have fluctuated throughout the years, he has consistently remained one of the top-paid officials in higher education.

Knapp clocked in as the 27th highest-paid university president in the nation in 2014 and dropped down to the No. 35 spot in 2015.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said compensation for all top earners is controlled by the Board of Trustees. An independent consulting firm provides information to the Board’s compensation committee to review salary data from executives at similar schools in similar positions, she said.

Six of GW’s 12 peer schools had administrators listed in the top 50 highest-paid executive salaries for higher education in 2015, according to data compiled by the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Csellar declined to say why Knapp’s salary increased from 2015 or what performance goals he hit to prompt the raise, but she said the committee takes accomplishments from the current fiscal year and goals for the upcoming fiscal year into account when determining compensation.

Three other top officials raked in more than $1 million in 2016 – Lou Katz, the outgoing executive vice president and treasurer, Jeffrey Akman, the dean of the School of Medicine and Health Sciences, and Shahram Sarkani, the director of the engineering management and systems engineering program. Sarkani is the first faculty member to bring in a $1 million paycheck in recent history and has been a top earner since 2011.

Katz’s earnings decreased from 2015, but Sarkani and Akman both received raises. Former Provost Steven Lerman earned more than $1 million that year, but his compensation decreased to about $760,000 after he left the University.

Provost Forrest Maltzman’s compensation increased by more than $200,000 between 2015 and 2016 – totaling more than $600,000 – when he became the permanent provost.

“Salaries for most senior administrators are reviewed by senior leadership and, in some cases, the Board of Trustees to ensure the compensation of an administrator is fair and equitable,” Csellar said.

She said salaries and bonuses are usually determined by evaluating factors like previous experience and “the qualifications that an employee brings to the job.” She declined to say what the benefits or drawbacks were of paying administrators increasingly high salaries.

“GW takes into consideration nondiscriminatory factors to ensure that compensation is commensurate with the administrator’s expertise, experience, history of publications and the value he/she will bring to the University,” she said.

Other notable pay raises include former Columbian College of Arts and Sciences Dean Peg Barratt and former professor of biochemistry Rakesh Kumar. Barratt stepped down in 2012 but received almost $200,000 in 2015. The next year, her pay jumped by 72 percent, bringing her total compensation to more than $330,000.

Csellar declined to say why Barratt’s salary and bonuses increased but said her compensation is based on her position as a professor of English, retirement contributions and “reportable benefits.”

Kumar was listed on tax documents for the first time in fiscal year 2017, bringing in nearly $800,000 in compensation in 2016. Kumar, who resigned two years ago, settled a lawsuit against the University in August 2016 for removing him from his position as chair of the biochemistry and molecular medicine department without following protocol.

Csellar said GW and the doctor reached an agreement but declined to say if his earnings were related to the settlement.

Kevin McClure, a professor of higher education at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington, said rising presidential salaries is a trend that has long existed across the nation – but the practice has elicited some controversy over the ethics of nonprofit businesses earning millions of dollars year to year.

“There are stories of students paying the bills, food insecurity and housing insecurity, while the president is making a million dollars,” he said. “The juxtaposition of those things raises big questions.”

He added that performance goals for additional compensation vary from president to president, but fundraising goals, which are typically listed in an executive contract, are one type of achievement that can trigger extra pay. Knapp saw the finish of the University’s largest fundraising campaign last year before he stepped down, which McClure said could have resulted in a bonus.

“It could be related to graduation or retention rate or outcomes like that,” he said. “As long as it happens to raise the profile and stature of the institutions.”

Jennifer Delaney, an associate professor of higher education at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, said that despite the budget cuts GW has undergone in the last three years, it isn’t unusual to see administrative compensation continue to rise because universities need to stay competitive to retain top managers.

Officials announced five years of 3 to 5 percent budget cuts in 2015 after an unexpected drop in graduate enrollment.

“It tends to be a complicated situation, but if you have fewer employees, you can pay them more,” she said.