It’s the conversation that no one wants to have: how to prepare for an active shooter on campus, or what to do if there is one. But after at least three shootings on college campuses so far this month, including one at a small community college in Oregon that left 10 people dead, we have to talk about it.

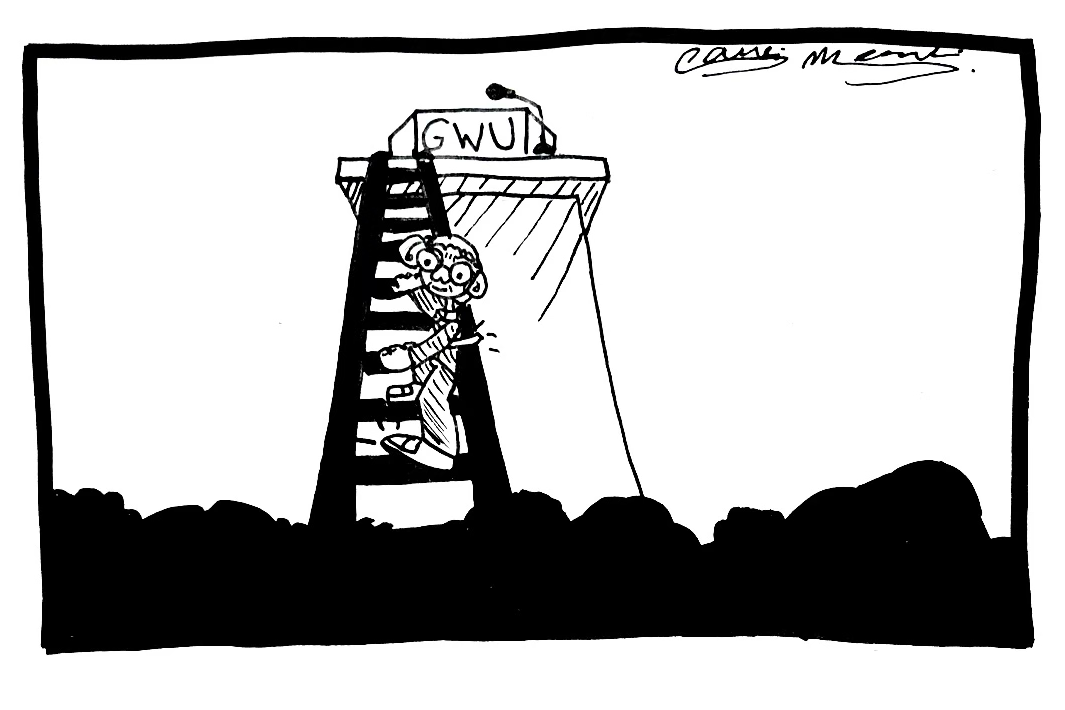

At a Faculty Senate meeting this month, University President Steven Knapp addressed campus safety, and said that GW is prepared.

“In the wake of the campus shootings, I want you to be aware that this is something we do pay a lot of attention to,” Knapp said, adding that shootings “seem to happen with great frequency.”

The last time GW’s University Police Department publicly dealt with a possible active shooter situation on campus was in November of 2013. After receiving reports of a gunman in South Hall, UPD waited 15 minutes to alert the Metropolitan Police Department about the threat.

Thankfully, there was no real danger. But if there had been, students could have been killed or seriously injured since UPD officers are unarmed and can’t do much to stop an active shooter without help from MPD.

Since then, we haven’t been given more information about University policies for an active shooter situation. Given the high volume of college shootings over the past two years, that’s unacceptable. Students will feel safer if they know what to do – or what police will do – in the event of an attack. And officials should do more than tell us they’re “paying attention.”

It could happen anywhere: Kogan Plaza, a classroom, Gelman Library or even the Vern Express. That’s why we have to plan ahead.

More formal means of prevention

While there is no foolproof method to prevent an active shooter situation, there are steps to take to help keep an attack from happening.

Our peer school Georgetown University, for example, has a threat assessment program, which allows students to email or call specialists if someone they know is displaying worrying behavior. The goal is to “identify, evaluate and address potentially threatening situations.” It operates similarly to the CARE report system in place at GW.

While GW mentions a threat assessment team on the UPD web site, the phone number listed is UPD’s general number and there is no discreet or anonymous reporting method. An anonymous online reporting system would be more effective because students and faculty could report suspicions, instead of fearing that just pointing something out would send officials into emergency mode.

GW should also train resident advisers and faculty to look for warning signs that a student is planning to harm others. Since RAs and professors interact with students on a daily basis, it’s likely they would be the first to notice if someone is acting strangely. RAs in particular have a unique opportunity to notice behavior that a student may hide or conceal in public.

Better coordination and training for UPD and MPD

Given UPD’s breakdown in procedure two years ago, it’s absolutely essential that UPD and MPD work out a better method of coordination – and that should include robust training. Senior Associate Vice President for Safety and Security Darrell Darnell said in an email that MPD, along with DC Fire and EMS, regularly do walkthroughs of GW facilities to familiarize themselves with campus. He said GW also holds biannual trainings for officers called “tabletops.”

“Later this semester, the University will conduct a full-scale emergency exercise that will include participants from GW Hospital and MPD,” Darnell said.

Running the scenario as if it were real is essential and would do much more good than just talking about what to do, so it’s admirable GW and MPD are already working on making that happen. While procedural details need to be kept under wraps, just knowing that the two departments are working together to practice can be a source of comfort for students.

MPD must also be actively engaged with the community. As our only armed protection, we have a right to know if they are prepared and how they will be able to coordinate with UPD. Whether the department has put together campus kits with maps and building blueprints or are conducting formal trainings inside of campus buildings, there’s no reason for MPD to keep those details hidden. MPD is responsible for our safety, and therefore it’s up to them to make us feel safe and confident in them.

We should also be open to a renewed conversation about arming UPD. In any emergency, UPD is our first line of defense, and in an active shooter situation, their lack of firearms could be extremely counterproductive. This isn’t a cure-all, though, and is just one possible defense mechanism to consider.

Instruction for students and faculty

In our day-to-day lives, we don’t talk about active shooter situations enough. Yes, it’s an uncomfortable and dark subject matter, but it’s critical to think about what to do ahead of time.

The only instruction immediately available to students is a PDF posted on GW’s website, which tells students to evacuate, hide out or take action, a plan the FBI endorses. Darnell said students also receive “emergency preparedness information” at floor meetings, and that preparedness materials are available to students.

But that simply isn’t enough. Students need more formal, up-front training about how to respond in an active shooter situation, whether in person or through an online training. Even just receiving reminder emails with instructional videos for an active shooter situation, like those sent the University of Wisconsin-Madison, could make students feel safer.

S. Daniel Carter, director of the 32 National Campus Safety Initiative for the VTV Family Outreach Foundation, established in the aftermath of the 2007 shootings at Virginia Tech, highlighted some steps that George Mason University has taken. The school has specified rallying points and has been clear about what needs to happen on campus, he said.

“You have to be prepared to assess situations and know if you need to hide, flee and how to attack as a group,” Carter said.

Each building on campus is unique, with different classroom layouts or areas for students, faculty and staff to gather. Faculty should know their responsibilities in an active shooter situation, and should be encouraged to share that information with students on the first day of class. Professors should know the best way to get out of a building, or how to properly lock the door.

Of course, there will always be shortfalls. We can never fill in all the gaps, or prevent every act of violence. But it would be worse not to try. It’s time to get serious about preventing and preparing for an active shooter situation. We’ve already waited too long.

The editorial board is composed of Hatchet staff members and operates separately from the newsroom. This week’s piece was written by opinions editor Sarah Blugis and contributing opinions editor Melissa Holzberg, based on discussions with managing director Rachel Smilan-Goldstein, sports editor Nora Princiotti, senior design assistant Samantha LaFrance, copy editor Brandon Lee and assistant sports editor Mark Eisenhauer.

Want to respond to this piece? Submit a letter to the editor.