Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Editor

Source: Institutional Research

At GW and its peer institutions, American graduate students in science, technology and engineering fields are on their way to becoming the minority.

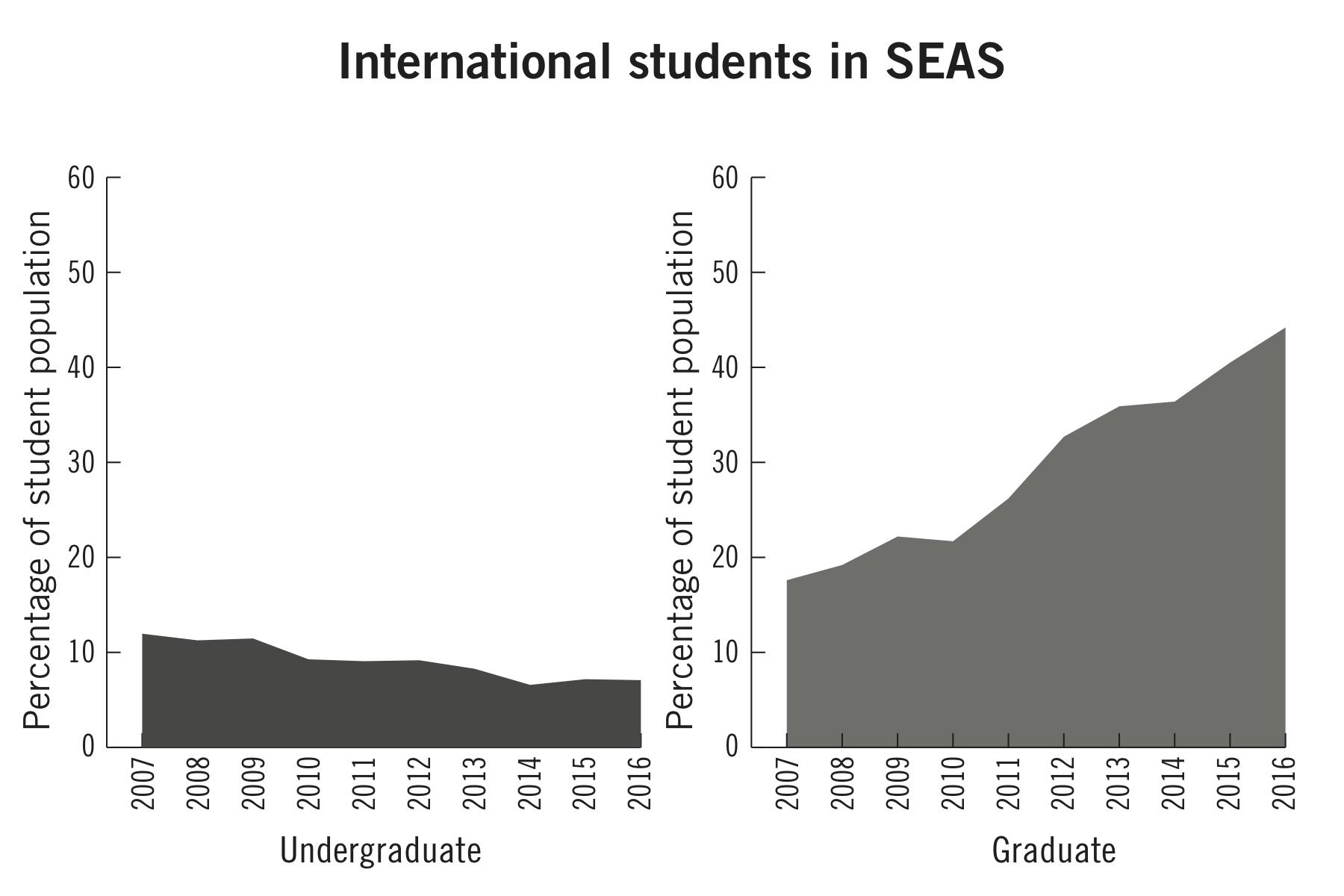

Last year, 44 percent of graduate students in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences were international, compared to just 7 percent in SEAS undergraduate programs, according to institutional data. Experts said the difference is likely cultural – American students want to jump into a career path, while international students are often more highly regarded at home for earning advanced degrees abroad.

The percentage of international graduate students in SEAS has soared in recent years, surging to 44 percent in 2016 compared to 18 percent in 2007. But at the undergraduate level, the proportion of international enrollment in the school has actually fallen from 12 percent in 2007 to about 9 percent in 2011 and 7 percent in 2016, according to institutional data.

The University has made a major push to boost its international enrollment over the last decade, hoping to double its international student enrollment to 15 percent of undergraduates and 30 percent of graduate students by 2022.

Over the past few years, officials have expanded resources for international students, hosting networking events and providing advisers to students. This summer, the Center for Student Engagement announced a new program for international students to help them adjust to campus.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said that generally international students stay in their countries of origin for undergraduate educations and head abroad for more advanced degrees.

“When the economy is not doing well, people tend to use the time to go back to earn an advanced degree or complete a certification,” she said in an email.

She declined to say if the University thought decreasing numbers of American students in graduate programs was a problem and if so, how the University is working to address it.

The trend is also prevalent at several of GW’s peer schools, notably New York University, where roughly 20 percent of undergraduate STEM students are international, but students from abroad dominate graduate programs with 80 percent coming from abroad.

In 2016, Syracuse University reported that 77 percent of its graduates in the College of Engineering and Computer Science were international, compared to just 8 percent of undergraduates in the same program.

The vastly growing job market in technology and the desire for universities and employers to remain competitive around the world contributes to the gap, according to an analysis of international enrollment numbers from The New York Times.

International students said Americans find a graduate degree in STEM fields less of a priority amid an improving economy, while students from other countries seek advanced degrees in the U.S. to send them on a path for better employment and industry connections.

Niveditha Nandakumar, a second-year graduate student studying engineering management, said she wanted to go to college outside of India, her native country, and was allured by the research opportunities available at GW.

“The jobs we get right after school here give us a little more than what we would get right out of school in India,” she said. “They land a better job here, and once they bring the experience back to India, they are valued more in India – they can use that leverage.”

Experts in undergraduate and graduate academic life said U.S. graduate students also reap the financial benefits of research grant funding – which students rarely receive outside the United States.

Jingwen Yan, an assistant professor of bioinformatics at Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis and an expert in international student affairs, said international graduate students find it easier to explore academic interests in their home country and seek higher-level degrees once they know what to pursue.

“Students majoring in STEM will get extra work benefits in the U.S. Graduate students with a career in mind may make decisions differently than undergrads who are still exploring,” she said in an email.

Lawrence Abraham, the associate dean of the School of Undergraduate Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, said international students overtake graduate classrooms because there is no admissions cap at the graduate level, a concept that could prevent universities from accepting well-qualified international students, instead of Americans, into STEM programs.

Universities aim to accept and enroll the most promising student body, which is often found in students outside of the U.S., he said.

“They have great competitive applications, they are well prepared to go on, but they just don’t have opportunities in their own country, or in some cases, even if they got it in their country they would not be as marketable,” he said.