Aaron Wang | Hatchet Designer

Source: Office of Development and Alumni Relations

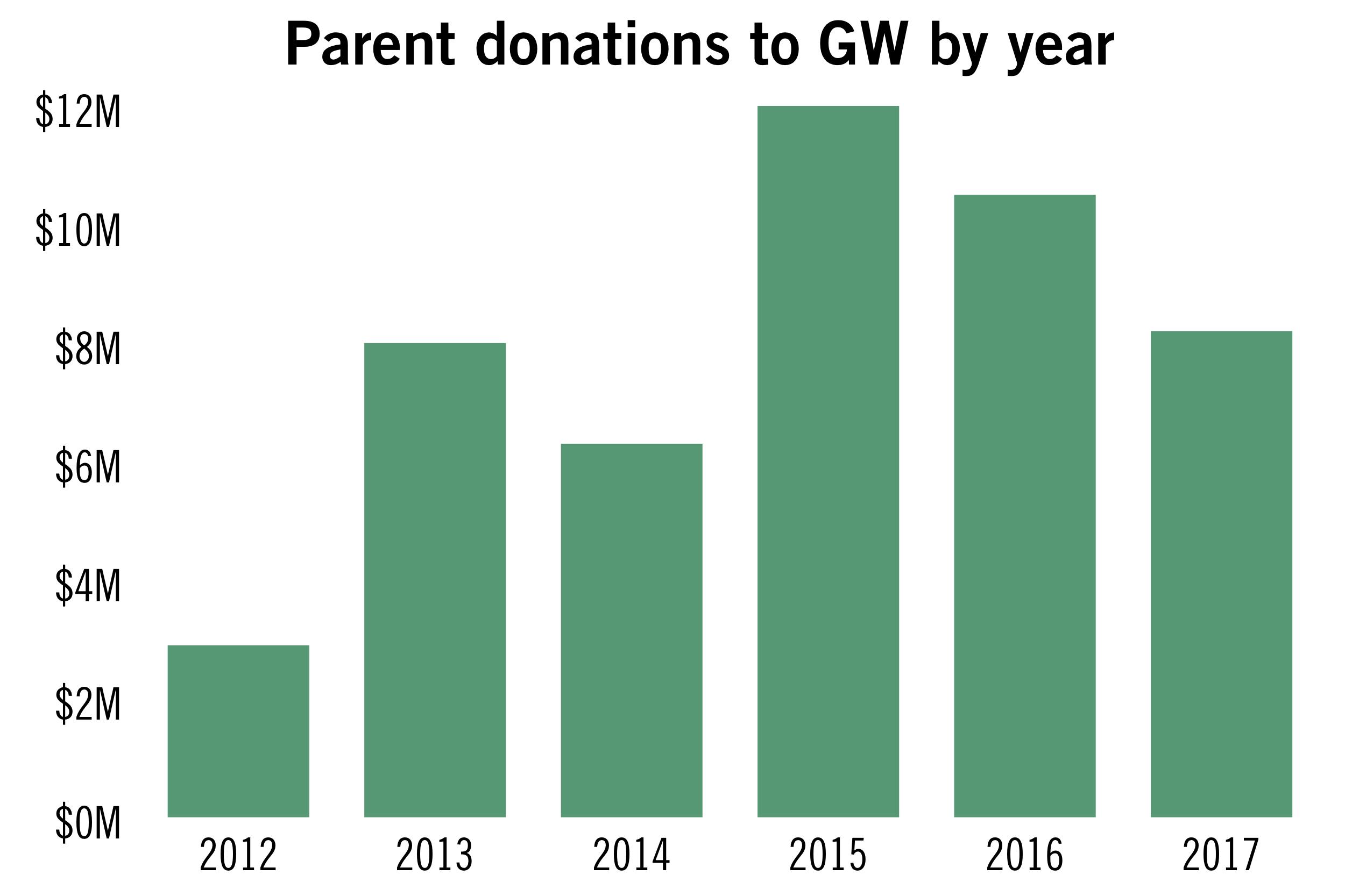

Parent donations to the University have fallen for the second consecutive year, following a multi-year surge in parent giving.

Parents of current students donated $8.5 million to the University in fiscal year 2017, which ended in June, dropping 20 percent from the previous year. Experts said parent donations can fluctuate depending on the intensity of fundraising outreach and how connected a parent feels toward their child’s education.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said parent donations help areas across the University, like the Knowledge in Action Career Internship Fund, a scholarship for students performing unpaid internships, and the Center for Career Services.

Csellar said parents contributed to The Store, a campus food pantry that opened last year, and a mentorship program for first-generation students that launched in 2013.

“GW family members are important stakeholders for the University,” she said in an email. “University events aim to engage families in the GW community and help them to identify the area of the University where they can make a difference through philanthropy.”

Parent donations peaked in fiscal year 2015 with $12 million raised, but fell 12 percent to $10.5 million in fiscal year 2016 and decreased another $2 million last fiscal year.

Csellar said officials generally expect to raise between $8 and $10 million each year from parents of current students.

The move comes after officials shook up parent services amid University-wide budget cuts. In 2016, officials dissolved the Office of Parents Services into a larger office within the Division of Student Affairs.

Csellar said those “organizational changes” did not affect parent giving and the Office of Development and Alumni Relations continues to partner with DSA for major events like Colonials Weekend – which featured parents and alumni this year in an effort to increase alumni interaction with current students and their families.

The drop in parent donations comes amid an overall rise in fundraising last fiscal year, when officials raised about $117 million as the University’s record-breaking $1 billion campaign drew to a close.

In fiscal year 2016, support from parents comprised 2.2 percent of total contributions to the University, down 0.6 percent from the previous year, according to data from Voluntary Support of Education, a data collection center.

Ann Kaplan, the director for Voluntary Support of Education, said while parents donations are not a large part of total giving at universities, they may increase during a strategic push like a capital campaign.

“It’s not a major component of giving,” she said. “Alumni giving is the highest percentage followed by foundations.”

Phil Hills, the president and CEO of the fundraising firm Marts & Lundy, said parents are more likely to contribute when they receive recognition for their donations, like invitations to special events or an appointment to an advisory board. Many times in the past, GW has renamed conference rooms or even entire buildings to honor major donors.

Most recently, the Law School Learning Center was renamed the Dee J. Kelly Law Learning Center this summer after a $1.25 million donation from Kelly’s foundation.

GW’s Family Philanthropy Board gathers influential parents of undergraduate students to spread awareness of programs like internship funds and financial aid, according to its website.

Hills said parent giving may fall if officials don’t directly advertise fundraising opportunities. Parents may not want to donate to a university because most are already paying their child’s tuition and don’t have extra money for philanthropy, he said.

Research has shown that some parents may contribute more to their child’s school than to their own university because they feel more connected to it at this stage of their lives, Hills said. He said parents tend to donate to universities at critical times during their child’s academic experience, like when they move to campus as freshmen or right before they graduate.

“I think most or many parents have other philanthropic priorities than just their child’s schools,” Hills said. “Over 90 percent of households make gifts, somewhere, so that’s a lot of competition to make in a lot of different places.”