Visitors get the chance to be the next Sherlock Holmes at the newest exhibit in the Renwick Gallery.

The “Murder Is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death” exhibit opened Friday and features 19 dollhouse-size crime scenes. The installation at the Renwick Gallery showcases the work of Frances Glessner Lee, the woman known as the “mother of forensic science,” and encourages visitors to participate in solving various unsolved murder mysteries laid out in the exhibit.

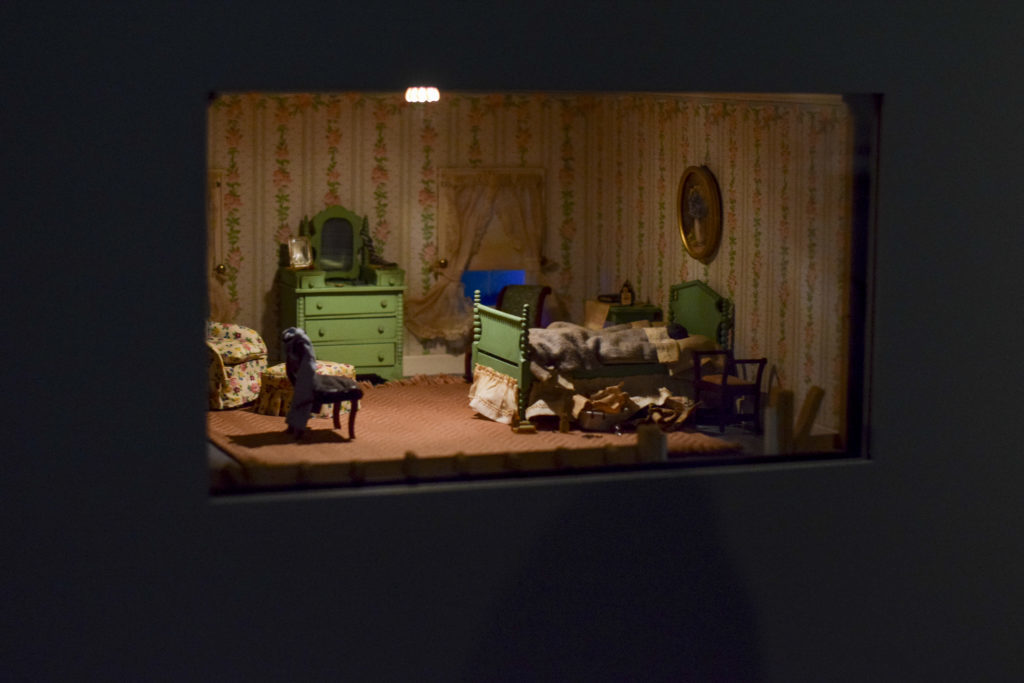

The exhibit features a series of sharply and carefully detailed dollhouse-sized crime scenes. The scenes blur the line between forensics and art with extremely intricate detail in their design but resemble real crime scenes.

Originally crafted by Lee to train homicide detectives, the displays depict true crime scenes from the first half of the 20th century. They were designed to push Lee’s trainees to meet her quest to “convict the guilty, clear the innocent and find the truth in a nutshell.”

The displays and detailed figurines challenge viewers to flex their deductive muscles to uncover the truth behind each crime scene. A flashlight is attached to every exhibit, allowing visitors to view the hidden details as if they were the detectives themselves.

One particular exhibit, “Kitchen,” depicts the death of housewife Barbara Barnes in the spring of 1944. The descriptive plaque explains the background of the incident, detailing how her husband Fred Barnes left the house for an hour and a half on an errand, returning to see his wife lying on the floor from the kitchen window.

The model shows the premises just before the police forced open the kitchen door. Each painstakingly crafted detail offers a different clue as to what actually happened. With pots and pans left askew, laundry still left out to dry, an ironing board set up in the corner and a fridge left ajar, the scene is very much alive. But visitors try to figure out if Barbara Barnes is dead.

Questions about whether she was murdered, committed suicide, killed by accident and when she died are all open ended. Visitors are left with all these questions, and the exhibit encourages them to think of their own answers. The wall adjacent to the exhibit is plastered with sticky notes where previous museum-goers have written their own theories on how Barbara Barnes met her untimely end.

Aside from the sticky note guesses, visitors won’t know the true conclusion because the stories featured stumped the professionals and remain unsolved.

Another display, one of Lee’s most provocative, is titled “Three-Room Dwelling.” The crime scene depicted here took place in the fall of 1937, and shows Robert Judson, a shoe factory foreman, his wife Kate and their baby Linda Mae all dead in various corners of their traditional middle-class house. The scene is gruesome. Blood stains every room. The once peaceful kitchen has blood cased bullet shells and a hunting rifle littered on the floor. Even the crib is covered with red.

People looking at this deadly scene don’t look in solemn silence, most of the visitors seem captivated with solving the mystery. They’re busy analyzing the blood splatters, examining the evidence and constructing their own personal theory on what happened.

Whether you’re an artist or a true crime buff, you’ll put on your detective hat and pull out a magnifying glass at this truly interactive exhibit. The exhibit is open daily at the Renwick Gallery on the corner of Pennsylvania Ave. and 17th St. NW from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.