While more minority students are attending GW than ever before – like nearly all major universities in the country – black and Hispanic undergraduates remain underrepresented on campus, according to an analysis by The Hatchet.

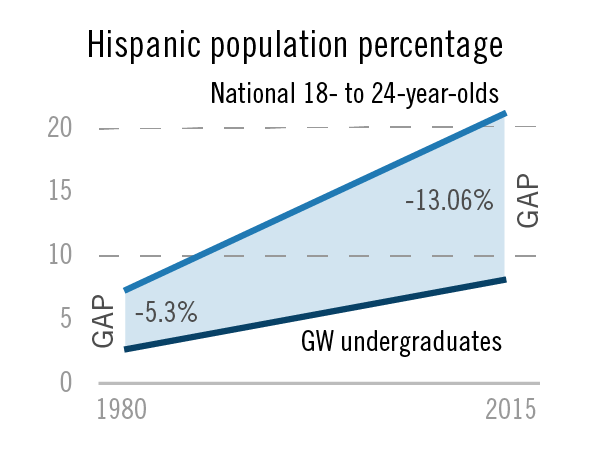

Hispanics are the most underrepresented ethnic or racial group at the University, making up 21.4 percent of the national college-age population but just 8.3 percent of GW undergraduates in 2015, the most recent year for which data is available from the National Center for Education Statistics.

[gwh_image id=”1038197″ credit=”Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Editor” align=”none” size=”embedded-img”]Source: National Center for Education Statistics and U.S. Census Bureau.[/gwh_image]

The group was more underrepresented in 2015 than it was 35 years ago, when GW’s Hispanic undergraduate population was 5.3 percent less than the national population, according to an analysis of census population estimates and enrollment data from the Department of Education.

The analysis shows that GW and its peer institutions still struggle to enroll historically disadvantaged groups, something experts said could limit social mobility and negatively impact the quality of education students who get to GW are able to receive.

Demographic and diversity experts said financial and accessibility obstacles unique to minority groups are the most likely explanation for the disparity, but it is up to universities to recruit and accept diverse groups of students – a major University goal for the past decade.

Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Eidtor

Underrepresented on campus

Dan Lichter, a sociology professor at Cornell University and an expert in population and demographic changes, said minority students often face social inequalities beginning in elementary school that make future success more difficult. Universities across the nation are trying to address those issues in their admissions practices, he said.

“Colleges are trying to pick up the pieces and identify students who can be successful in their environments, but we’ve already created an environment where we’ve got so many disparages across different racial, ethnic and immigrant groups that it’s really hard for universities to know how to respond,” he said.

GW is not alone in enrolling black and Hispanic students at a lower rate than the general population. An analysis of GW’s 14 peer schools shows that the University’s competitors similarly underrepresent those students.

Even at the University of Miami, the only one out of GW’s peer institutions to overrepresent Hispanics, the undergraduate population was only 1 percent higher than the group’s share of the national population in 2015. The city of Miami has one of the highest Hispanic populations of any major U.S. city.

On average, GW and its peer institutions underrepresented Hispanics by 11.3 percent in 2015, compared to the overall percentage of 18- to 24-year-olds in the country. GW’s D.C. peers did not fare much better than the University, with Georgetown University facing a 13.7 percent disparity and American University underrepresenting Hispanics by 10 percent.

Ninety-one percent of GW undergraduates are 24 years old or younger, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

A similar analysis by the New York Times found a similar trend across 100 universities nationwide, including some of GW’s peer schools.

Although more Hispanic students are attending GW than 35 years ago, the increase failed to keep pace with the rapid expansion of the Hispanic population in the U.S. – one of the fastest-growing minority groups in recent decades. The college-age Hispanic population increased by nearly 14 percent between 1980 and 2015, according to census estimates.

Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Eidtor

Addressing inequality

Laurie Koehler, the vice provost for enrollment and retention, said although the University has made improvements in enrolling a diverse student body, “we also have more to do.”

“At GW, we believe that graduating an academically talented and diverse student body is critical to our success as a university and enhances the educational experience for all students,” she said in an email.

In 2015, the University opened the Cisneros Hispanic Leadership Institute and started the Cisneros Scholar program, offering scholarships to students interested in leadership and service in the Hispanic community. While all students can participate in the program, preference is given to individuals of Hispanic origin.

Black students were also underrepresented at the University in 2015, with undergraduate enrollment 8.7 percent lower than the national black population. Black students were underrepresented by more than 5 percent at all 14 of GW’s peer schools that year.

The proportion of the black undergraduate student population at GW increased by less than one percent between 1980 and 2015, the analysis found.

The change in black student representation in the U.S. between 1980 and 2015 could not be measured because of how the 1980 census categorized racial groups. Current census estimates allow races to be differentiated by Hispanic origin and non-Hispanic origin, but they were not in 1980, the first year for which enrollment data was available for the education department.

Officials have created programs and changed policies in recent years with the goal of increasing diversity and improving accessibility. In 2015, the University implemented a test-optional admissions policy after reviewing research showing an emphasis on standardized test scores puts historically disadvantaged groups and first-generation students at a disadvantage, Koehler said. The change led to a dramatic 28 percent increase in applications in 2016.

Koehler said the University has also made efforts to increase diversity through partnerships with scholarship programs like The Posse Foundation, which offers full-tuition scholarships to students in Atlanta-area public high schools. Officials have long offered full-ride scholarships to D.C. public school students through the Stephen Joel Trachtenberg Scholarship.

“It is important for us to reach out to potential students who might not realize that a GW education is something that is within their reach,” Koehler said.

Former University President Steven Knapp launched a president’s council on diversity and inclusion in 2010 and a task force to help low-income students attend GW in 2014.

The efforts have increased the number of minority students on campus, and last year’s freshman class was the most diverse in University history with more than one-fifth of students coming from underrepresented groups, officials said.

Accounting for overrepresentation

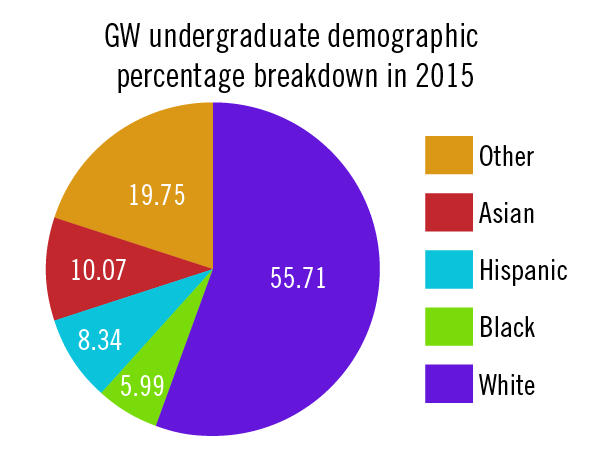

The only two groups to be overrepresented at GW were white and Asian undergraduate students.

White students, who represented 55.7 percent of GW’s undergraduate population in 2015, were slightly overrepresented, but some of GW’s peers, like New York University and the University of Southern California, underrepresented white students.

Asians were the only consistently overrepresented racial group at GW and across peer schools. Only one peer institution – Tulane University – underrepresented those students.

Tom Guglielmo, an associate professor of American studies with expertise in race and ethnicity, said the overrepresentation of Asian students is a “complex” topic that may be influenced by significant post-1965 Asian immigration to the United States.

“Substantial percentages of these newcomers have been highly educated – M.D.s, Ph.Ds, engineers – and their kids have tended to excel at school, just as they did,” he said.

But after years of affirmative action, experts still debate why minorities like blacks and Hispanics struggle to gain entry to top universities in large numbers. In 1980, Hispanics and blacks comprised only 2.1 and 5.2 percent of the undergraduate population at GW, respectively. In 2015, the groups made up 8.3 and 6 percent of undergraduates, respectively, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Guglielmo said financial obstacles are an enormous barrier for many students – but particularly for those from underserved communities.

“GW’s extraordinarily high price tag must scare away lots of low-income and even moderate-income prospective applicants,” he said. “And among those who do choose to apply, those applicants with more money, all things being equal, have a better shot of getting accepted at GW.”

In 2013, the University admitted to putting applicants who could not afford tuition on a waitlist despite claiming for years to be need-blind in its admission policies.

Michael Wenger, a sociology professor with expertise in race relations, said pre-college education could also contribute to the disparity because public schools that are primarily non-white often have fewer resources than majority-white elementary, middle and high schools — which helps “maintain the kind of achievement gap we have today.”

“I think universities should play a much larger role in trying to ensure that public education for students from all racial and ethnic groups that the education and resources are far more equitable than they are now,” he said.

Dani Grace, Leah Potter and Meredith Roaten contributed reporting.