Graduate School of Education and Human Development faculty have ranked among the lowest-paid professors at GW since 2020, which faculty say underscores the University’s salary inequity and GSEHD’s financial limitations.

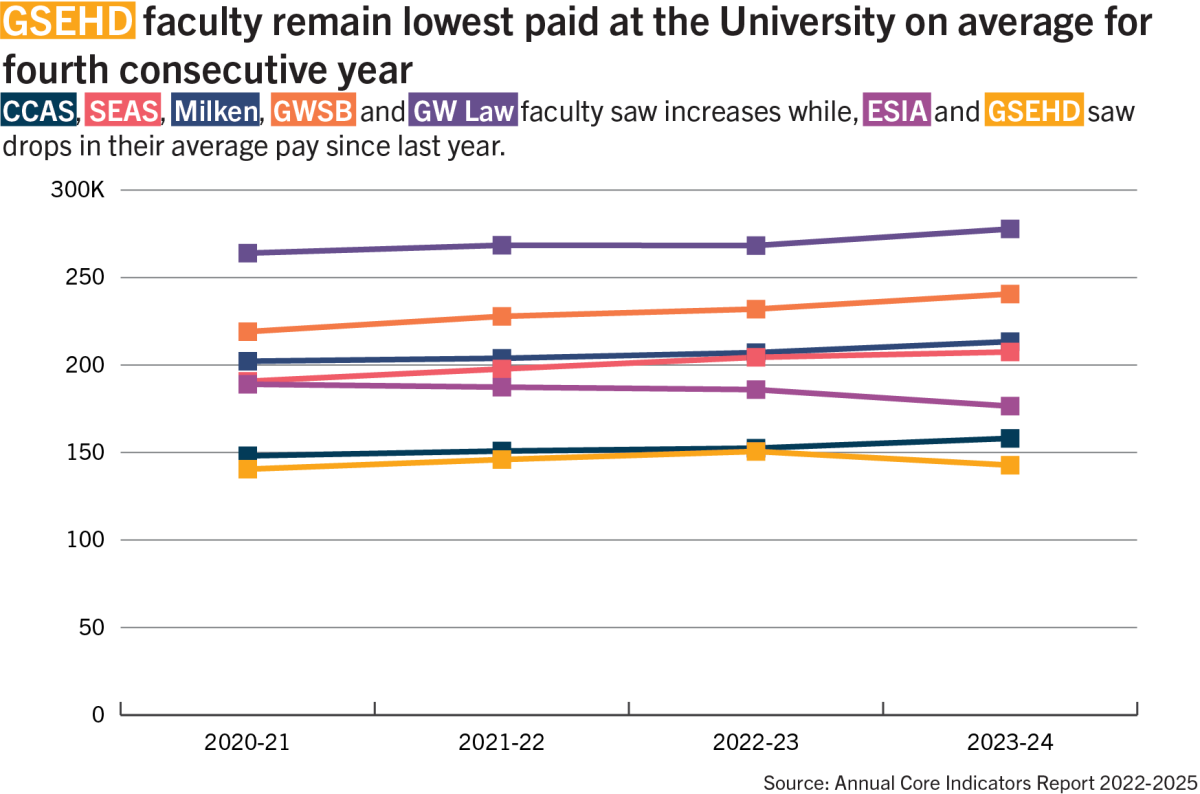

GSEHD assistant professors on average were the lowest-paid faculty members among nine of GW’s schools and colleges for the last four academic years, while GSEHD professors were the lowest paid for the last three years, according to the University’s annual core indicator reports from the past four years. Faculty in the school said their salary does not reflect the credentials and value they bring to the University and are reflective of the school’s financial limitations, like market conditions, tuition dependence and budget model restrictions.

GSEHD assistant professors made an average of $93,186 during the 2023-24 academic year, 15 percent less than the University-wide average for assistant professors of $109,437, according to the 2025 report. Full professors in the school made an average of $142,784 last academic year — the lowest average for the position within GSEHD since the 2020-21 academic year — and falling over $50,000 short of the University-wide average during the 2023-24 academic year of $193,261.

During the 2022-23 academic year, the role at GSEHD reached an average salary of $150,612, the highest average salary for the post in the last four years, according to last year’s report.

Michael Feuer, the dean of GSEHD and a professor of education policy, said the school “greatly values” the work of its faculty and their commitment to the University’s educational and research mission. GSEHD has worked “diligently” over the past several years to increase faculty salaries and has “made progress” on salary equity, he said.

“We are constantly evaluating the needs of our faculty and assessing feedback to ensure all faculty feel supported and properly compensated,” Feuer said in an email.

Shaista Khilji, the chair of GSEHD’s Department of Human and Organizational Learning and a department professor, said GSEHD faculty are “acutely aware” of the inequity and disparity of their pay and feel that their compensation does not reflect their teaching, research and service contributions to the University.

Khilji said she responded to The Hatchet’s questions after conversations with several other GSEHD faculty members, including Brian Casemore, an associate professor of curriculum and pedagogy. The other faculty members she spoke to besides Casemore were not comfortable sharing their names, she said.

“For us, this salary gap is not just about numbers on a paycheck — it’s about institutionalized inequities and how the GW administration has continued to reinforce and sometimes even defend it,” Khilji said in an email.

Khilji said officials have told faculty that salaries correspond to each discipline, but some faculty believe that the argument “downplays” the importance of education as a field of study.

GW Law, the School of Business and the School of Engineering & Applied Science were the three highest-compensated schools last year, according to the 2025 report.

“Unfortunately, the blatant defense of inequities further reinforces the problem and exposes the gaps between admin talk (of equity) and their walk,” Khilji said in an email.

Khilji said GSEHD faculty would like the University to work with GSEHD’s leadership to identify faculty who fall below GW’s average salary, market basket universities and the American Association of University Professors’ 60th percentile and develop a three-year, transparent plan to close salary gaps.

She said despite officials’ efforts over the past five or six years to address salary equity among “selective” faculty through the salary equity review process, most faculty members in GSEHD have salaries lower than the AAUP 60th percentile benchmark and average salaries at the University.

The AAUP, a group of nationwide University faculty and researchers, calculates its 60th percentile benchmark from its annual faculty compensation survey, which was $160,322 for professors, $115,406 for associate professors and $99,878 for assistant professors, all higher than GSEHD faculty salaries, except for associate professors, according to the 2025 core indicators report.

She said pay disparity and inequity at GSEHD has been a “chronic” and decades-old problem, which faculty have raised to administration over the last 20 years.

Feuer said in 2019 that the school has looked closely at salary equity and increased the percentage of faculty earning compensation that is “respectable” compared to peer institutions.

“We had to devote some of our hard-earned savings, and we made sure that people who were vulnerable to this kind of salary inequity, that we paid extra attention to their performance, to their productivity and to what they were doing, and in cases where the productivity and performance warranted, we made an even bigger boost,” he said in 2019.

Dwayne Kwaysee Wright, an assistant professor of higher education administration, said he is not comfortable with his salary as a professor since it does not completely reflect his degrees and credentials but is “fine” with his total compensation from the University as he also serves as a co-program director and the director of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives at GSEHD — which contribute to his income — and as a faculty-in-residence, which helps him save money on housing costs.

He said part of the reason the GSEHD’s salary averages are less than other GW schools is market conditions because it is more costly for the University to hire a lawyer or doctor to serve as a faculty member because they are competing with other employers offering higher salaries. He said it is cheaper for the University to hire someone with an education background since competing employers tend to pay them less.

The average education professor makes a median salary of $73,240 compared to a law professor who makes a median wage of $127,360, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“They may be excellent at their job, but the maximum amount that they can actually make pales in comparison to a doctor,” Wright said.

Wright said the University’s budget model also requires GSEHD to give the same percentage of its tuition revenue back to the University as other schools, despite bringing in less money than other areas of GW, like the law school.

The University’s current budget model, adopted during fiscal year 2017, makes graduate schools give 30 percent of their on-campus tuition revenue, 20 percent of their off-campus tuition revenue and 15 percent of their online tuition revenue to the University for its budget, according to a presentation from former Provost Forrest Maltzman to the Faculty Senate in 2016.

University President Ellen Granberg announced in September that the University had begun talks with Grant Thorton, an independent Certified Public Accountant firm to receive input on revising the University’s budget model.

“Apparently, there are faculty and administrators that are working on reworking the budget model, but we’re going to suffer here in GSEHD until that happens because the numbers that you might see on a spreadsheet really do not do justice to the value we bring to GW,” Wright said.

Experts in higher education said it is normal for education faculty to be among the lowest paid at universities nationwide since salaries often correlate with a professor’s discipline and education programs often have less revenue and resources than medical, law and engineering schools.

Rob Toutkoushian, a professor at the Institute of Higher Education at the University of Georgia, said universities have to compete with other institutions and outside industries to hire faculty and education professors often cost less than someone in law, engineering or business.

“A school like GW doesn’t really have much choice other than to pay differential salaries to people by their field,” Toutkoushian said.

Zach Taylor, an assistant professor of education at the University of Southern Mississippi, said GW’s budget model setup can have a larger impact on the revenue of schools like GSEHD since they do not have as much revenue compared to a higher-resourced school, like the law school.

Taylor said if a University wants to increase salaries for GSEHD, they would either need to find additional funds through raising student tuition or implement revenue sharing to reallocate funds from “wealthier schools.”

“If you’re taxing at the same rate to a ‘lower income, lower’ resource school, that percentage is going to be a bigger hit in their budget than it will be on the higher income majors,” Taylor said.