The White House and Capitol Hill are not the only epicenters of political scandal in the District.

Since the Board of Trustees chartered it in 1976, the Student Government Association has become notorious for inner turmoil, conspiracies and power struggles. From a famed actor’s presidential campaign loss to an infamous coup, here are our picks for the most noteworthy SGA scandals since its establishment.

The story behind Alec Baldwin’s name

Actor Alec Baldwin, best known for his role as Jack Donaghy in the sitcom “30 Rock” and his stint impersonating President Donald Trump on “Saturday Night Live,” sits at the center of venerated GW lore passed down through generations of students. Half the school has heard the story of the celebrity alum who ran for president of the SGA — then the GW Undergraduate Student Association — in 1979, lost and then transferred to New York University all in the same semester.

That story isn’t quite true. Alec Baldwin never went to GW — back when he was a student here, he went by Alex Baldwin, only changing his name after transferring to NYU. Whether or not the shame of his SGA presidential loss sparked the name change remains to be seen.

In the 1979 SGA race, Baldwin branded himself a reform candidate, writing in his platform that “the administration is deliberately striving to keep its student body in the dark about what they are doing with our money and our education,” according to a Feb. 25, 2002, Hatchet article.

Baldwin finished the race in third place, just below the cutoff for the top-two runoff by a single vote.

Decades after the loss, the actor seemingly harbored lingering resentments for GW. He told the Washington Post in 2010 that “People went there for two years because they didn’t get into the Ivy League school that was their first choice. Then you’d transfer to the school you really wanted to go to.”

One person who didn’t want Baldwin to hold any ill will toward his alma mater was former President Richard Nixon. Mark Weinberg, a mutual friend, told Nixon about Baldwin’s loss, and Nixon — no stranger to presidential crash-outs himself — wrote Baldwin a letter.

“The important thing is that you cared enough to enter the arena, and I urge you to look upon the contest as a learning experience which will serve you well in the future,” Nixon wrote.

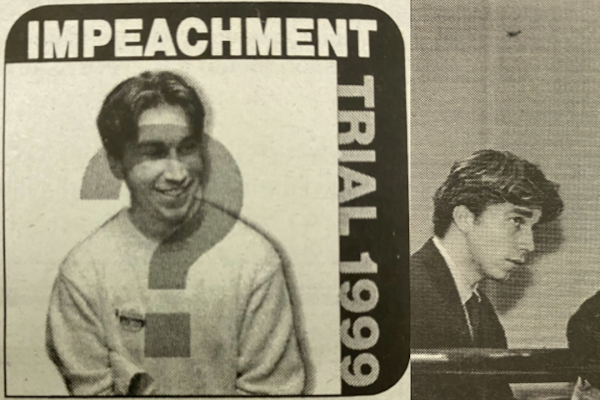

Running late to almost not running at all

The impeachment trial of former President Bill Clinton wasn’t the only political controversy shaking up the District in 1999. Team Meisner-Sadler, an alliance of SGA presidential candidate Phil Meisner, executive vice presidential candidate Cat Sadler and 12 SGA Senate candidates, ran a coalition campaign under the tagline “When Lightning Strikes.” But the Joint Elections Committee killed Team Meisner-Sadler’s spark when they removed six of their candidates, including Meisner and Sadler, from the ballot.

The removal came after Meisner arrived 15 minutes late to a mandatory JEC meeting, where he was supposed to represent himself, Sadler and four of the SGA senate candidates in their coalition. At the time, JEC rules stated that they would remove any candidate who showed up more than 15 minutes late to a mandatory meeting from the ballot.

The JEC scheduled a hearing to review the situation later that week, but Meisner seemingly hadn’t learned his lesson and showed up 30 minutes late to that meeting as well. While Meisner was not present, the JEC decided to remove him and his team’s five other candidates from the ballot. Meisner and Sadler filed an appeal immediately after the decision, and the JEC scheduled an appeals hearing for that night at 7 p.m.

But Meisner and JEC Chair Kevin Burkett had different understandings of whether or not Meisner was supposed to attend the appeals hearing. While Meisner believed he did not have to attend, Burkett said it was clear that Meisner needed to be at the hearing to present “new evidence” in the case. Meisner arrived an hour late to the hearing and opted to file another appeal with Sadler that weekend.

The six Team Meisner-Sadler candidates axed from the ballot ran a write-in campaign for the rest of the election cycle, and Meisner secured the SGA presidency after a runoff against opponent Alexis Rice.

But just like Clinton before him, Meisner’s presidency was shrouded by an impeachment — except instead of charges of perjury and obstruction of justice it was over the misuse of SGA funds. Clinton got off scot free, but Meisner wasn’t as lucky and was removed from office in November 1999.

The plots of Justin Neidig

If anyone ever cared about the sanctity of postering day, it was 2005 JEC chair Justin Neidig. Neidig brought charges against one candidate vying for the SGA presidency that year, Ben Traverse, who supposedly “made use of internet campaigning” too early rather than starting by putting posters up around campus, according to a Feb. 24, 2005, editorial.

Hatchet columnist L. Asher Corson claimed Neidig had other motives: Neidig and Traverse had long-running beef, and Corson was convinced that Neidig wanted to see his nemesis go down. Neidig hit Traverse with four of the seven violations needed to get kicked off the ballot and tried to remove the one dissenter from the JEC vote, Christopher Jenkins, for supporting Traverse.

Jenkins stayed on the commission, but Traverse wasn’t out of the woods yet. He finished in first place in the election but fell short of 50% of the vote, sending him into a runoff against fellow candidate Audai Shakour. Traverse again faced JEC charges, with Neidig accusing the candidate of failing to list palm cards they bought on a campaign finance report and of holding a rally at a Thai restaurant, a violation of JEC standards which would’ve disqualified Traverse from the runoff.

Traverse was acquitted, but it didn’t matter. He lost to Shakour in the runoff.

The attempted coup of 2022

In July 2022, when members of the SGA could have been lounging on a beach or even interning on the Hill, they instead attempted to dethrone the sitting SGA president.

Just over three months after his election, Christian Zidouemba’s presidency hung in the balance as five members of his own executive cabinet attempted to remove him from office.

The power struggle unfolded after the cabinet members said he initially threatened to fire members who listed their formal SGA titles in an open letter calling on officials to remove Justice Clarence Thomas from his GW Law teaching position in light of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade. Zidouemba later allowed members to write their titles in the letter and said he “never intended to fire anybody” in his cabinet.

On the evening of July 1, five executive cabinet members unanimously voted to remove Zidouemba under Article 15 of the SGA Constitution, which at the time allowed the executive cabinet to permanently remove the president through a unanimous vote, calling him “erratic” and unfit to lead the SGA. Less than 15 minutes later, Zidouemba fired two of the executive members who voted to remove him “for failure to properly execute their duties,” before he even learned of the vote to remove him.

“I’m still the president of the SA!” Zidouemba wrote in the caption of a video posted to Instagram that he filmed while working at CVS. “A power hungry cabinet is attempting to misuse Article 15 to remove me from power while I’m at work and can’t respond.”

The next day, two executive cabinet members withdrew their votes to remove Zidouemba, saying they “misunderstood” Article 15, while at least seven members of the executive branch resigned in the aftermath of the incident. Zidouemba continued to serve as the confusion lasted through October 2022, when the Student Court unanimously ruled that he was the legitimate president and could remain in his position after a monthlong judicial process.