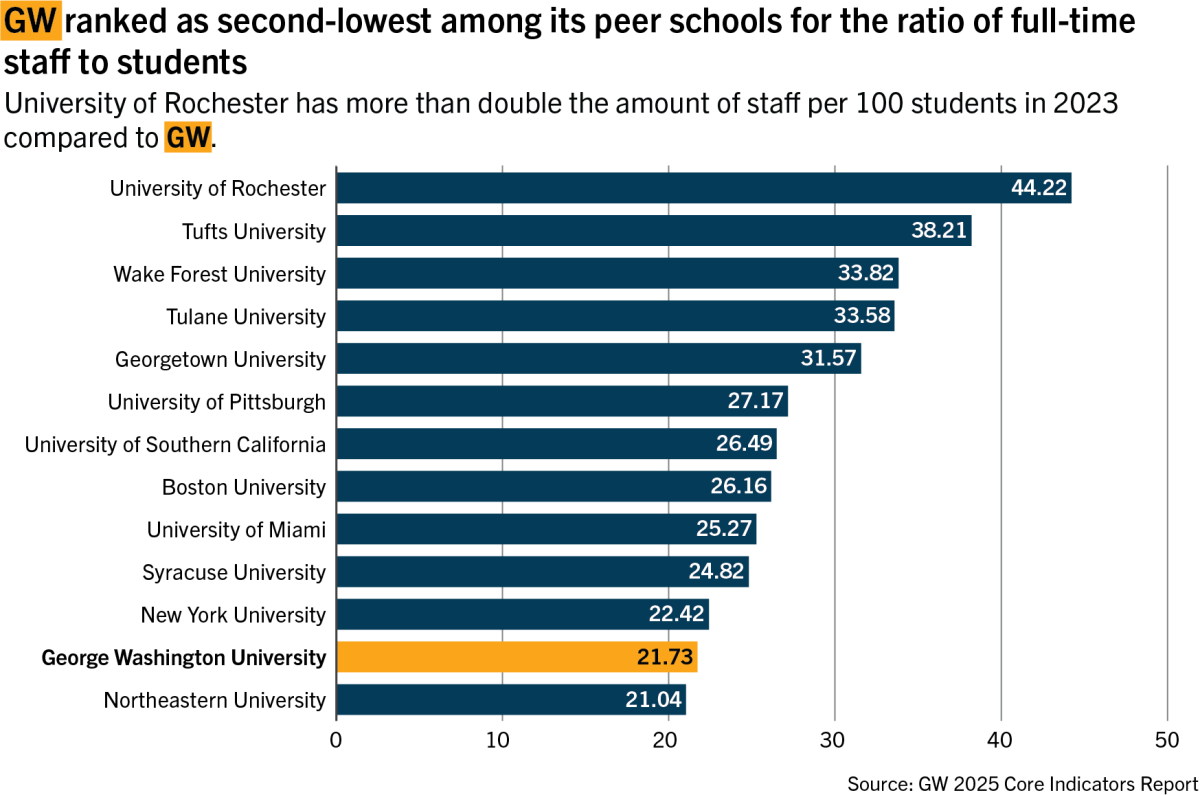

The University’s full-time staff-to-student ratio was the second-lowest out of its 12 peer schools in 2023, a dip that experts warn may heighten staff burnout and impede student and faculty support.

GW’s ratio of full-time staff to students sat at roughly 21.5 to 100 in 2023, which Provost Chris Bracey said at a Faculty Senate meeting earlier this month demonstrates officials’ need to prioritize hiring additional staff, given that student success hinges on the support that staff bring to different departments. Bracey said the University is in the process of hiring additional staff, which education experts say will help mitigate staff burnout and improve the student experience.

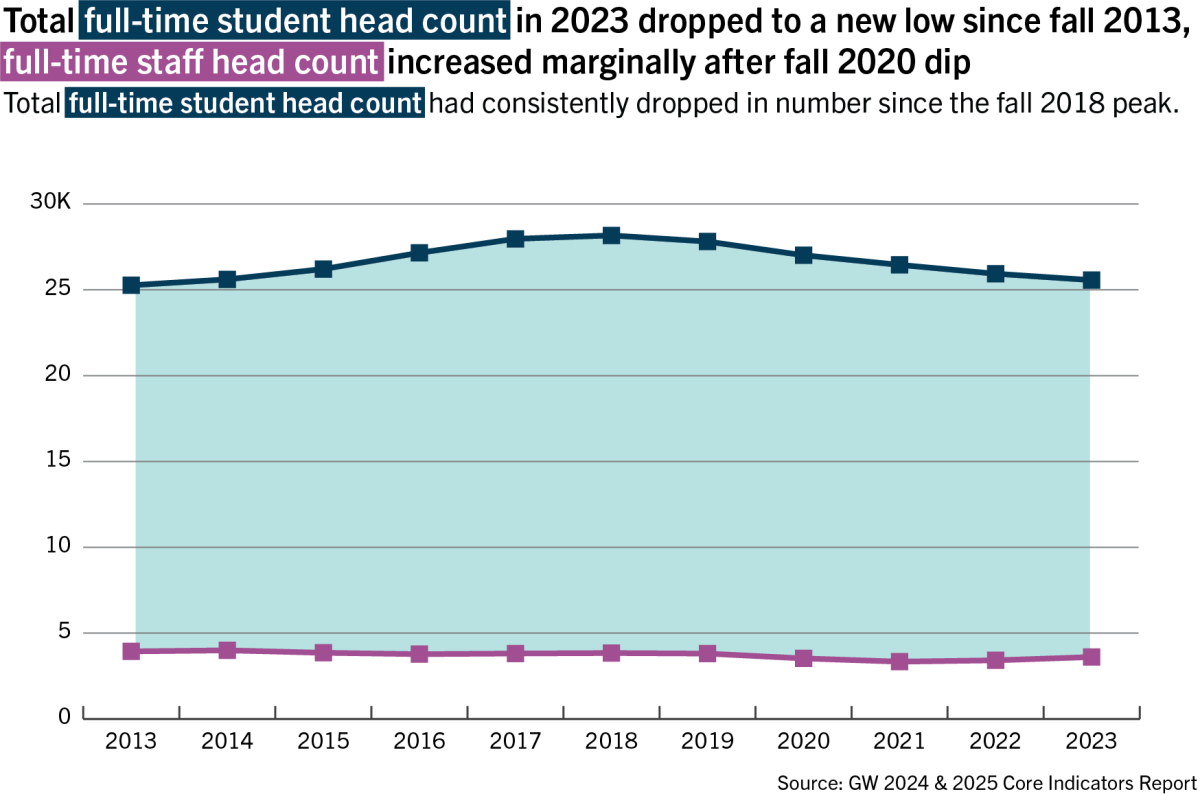

Last year, GW ranked third-to-last on its full-time staff-to-student ratio in comparison to peer schools in 2022, landing above Northeastern University, with a staff-student ratio of almost 20 to 100, and New York University, with an average of just over 21 staffers per 100 students.

In the 2023 data, NYU’s ratio rose to almost 22.5 staff for every 100 students and Northeastern’s ratio increased to roughly 21 to 100. GW’s ratio remained relatively unchanged, moving from 21.49 staffers per every 100 students in 2022 to 21.73 in 2023.

The University of Rochester had the highest staff-student ratios in both the 2022 and 2023 data sets at 44 to 100. Tufts University took second place both years, with 38 staffers per every 100 students in 2023.

Bracey said at the meeting that the University will focus on increasing staffing at student and faculty facing offices like IT, “building services” and Disability Support Services. DSS staffing this year grew from seven personnel in June to 14 by November after a period of high turnover, which students said limited support last year.

“The good news is that we’re staffing up to restore some of those key functions that are needed to advance our academic enterprise,” Bracey said at the meeting. “We’re going to continue to do that to ensure that the experience of our faculty and students meets the expectations established by our reputation and, perhaps more importantly, by our price tag.”

Bracey’s comments came two weeks after officials announced that GW is implementing a “position management review process,” meaning promotions and hiring require an extra “level of review” by University leadership before approval. The new process aims to ensure GW stays within its budget in response to the headwinds in higher education posed by President Donald Trump’s recent executive actions, officials said.

Since taking office in January, Trump and his administration have worked to dismantle what they see as a liberal bias in higher education, threatening or pulling funding from institutions that do not align with the administration’s curriculum, staffing and admission priorities.

The Staff Council released a statement in response to the announcement in late February, where they said staff members are “deeply concerned” about the position review’s implications, adding that the language raised concerns about potential job cuts.

University spokesperson Julia Garbitt said officials have made “many efforts” to address “employee concerns,” adding that faculty and staff retention is of the “utmost importance” to the University. She declined to comment on which specific steps officials are taking to increase staffing and the timeline for hiring additional staff.

Garbitt said the University continues to monitor its financial situation and evaluates financial benchmarks to determine which changes they can make that will continue to support the community. She said it’s important the University stays prepared for any “financial difficulties” in the road ahead.

“The well-being and retention of staff is a priority, and the University is committed to offering as many resources and support systems as possible,” Garbitt said.

Higher education experts said low staffing feeds staff fatigue, hampering student and faculty experiences. But they warned that hiring additional staff is “very difficult” and uncertain under the Trump administration, especially as the federal government continues to strain universities’ financial resources.

Robert Kelchen, who heads the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, said GW’s staff-student ratio means “there are questions” about whether students can access support when they need it. Kelchen said additional staffing decisions would go through the “highest levels of University administration” and likely take up to two years to do “strategic hiring.”

The University can target adding a few additional staff in key positions, like financial aid counselors in the short term, but without “a big initiative” or budget cuts, options to improve staffing are limited in the long term, he said.

“The number of staff just does not change that fast,” Kelchen said. “The way to change the ratio, to make the ratio better, is either basically by adding staff or having fewer students.”

KC Culver, an assistant professor of higher education administration at the University of Alabama, said hiring more staff will help students and employees feel more supported, providing extra resources to students while also lowering the workload on individual staff members.

She said the University should focus on creating clear pathways for staff promotions and engage in professional development because all employees want opportunities for growth at their job. More than 50 percent of staff surveyed last year reported that they believed they could find more opportunities for professional growth if they left GW.

“Those are things that are often easier to implement than huge salary increases or pay increases for our hourly employees,” Culver said.

Culver also said more staff would benefit professors and other faculty, as they could handle administrative work like reserving classrooms or scheduling conferences. When professors don’t have this help, they have less time to focus solely on teaching, which reduces students’ quality of education, she said.

“If there’s a low number of those, it means faculty then are having to take that work on themselves and that means less time for focusing on teaching, lesson plans, interactions with students,” Culver said.

Culver also said GW’s location in D.C., which houses six other universities, could prove challenging to staffing, as employees might choose other institutions if GW’s compensation is insufficient. More than 65 percent of staff surveyed last year said they believe their compensation was “not sufficient” given the work they do.

“GW faces more institutional competition for staff people because of it being located in a really higher education-rich environment,” Culver said.

Gary Rhoades, a professor of higher education at the University of Arizona, said there is often too much “bloat” in higher education, which can hurt students because university leaders are prioritizing hiring people for top administrative position and forgoing an effort to staff student-facing positions.

He said the gap between a president of a university’s salary and that of someone like an advisor’s salary is “greater today” than it’s ever been in American higher education.

Former Interim University President Mark Wrighton made more than $1.2 million during fiscal year 2023, according to the University’s most recent Form 990, which reports two years behind the current fiscal year. A current job posting for an academic advisor for the School of Nursing lists the salary range as between $43,888 and $67,655.

Rhoades said the University should focus on adding staffing positions to areas that are most directly linked to student life and the student experience, as Bracey recommended at the Faculty Senate meeting. He said burnout among staff members can particularly dampen those that are student facing, as they become less available and are “running on fumes” when working with students.

DSS staff, who are responsible for providing classroom accommodations and assistive technology for students with disabilities, reported in 2023 that they were leaving the unit after struggling with low staffing and increased work responsibilities.

“It plays out both in morale and then that directly impacts the student experience,” Rhoades said. “Staff are trying, they generally care a lot about the students they work with, just like faculty do. But there’s also just the reality of how much time in the day you have and what your workload is.”

Rhoades said it will take GW “a number of years” to redress staffing shortages, but he recommends officials set “realistic targets” for the future, and begin redirecting funding from senior positions to entry-level, student-facing positions.

He also said officials should engage with staff — including the Staff Council and the adjunct and part-time faculty union — to understand how the University can best increase staffing, given they are the people who understand the issue to the largest degree.

“If you’re trying to solve a problem with regard to staffing and you’ve got a Staff Council and you’ve got an adjunct faculty union, talk to them,” Rhoades said.