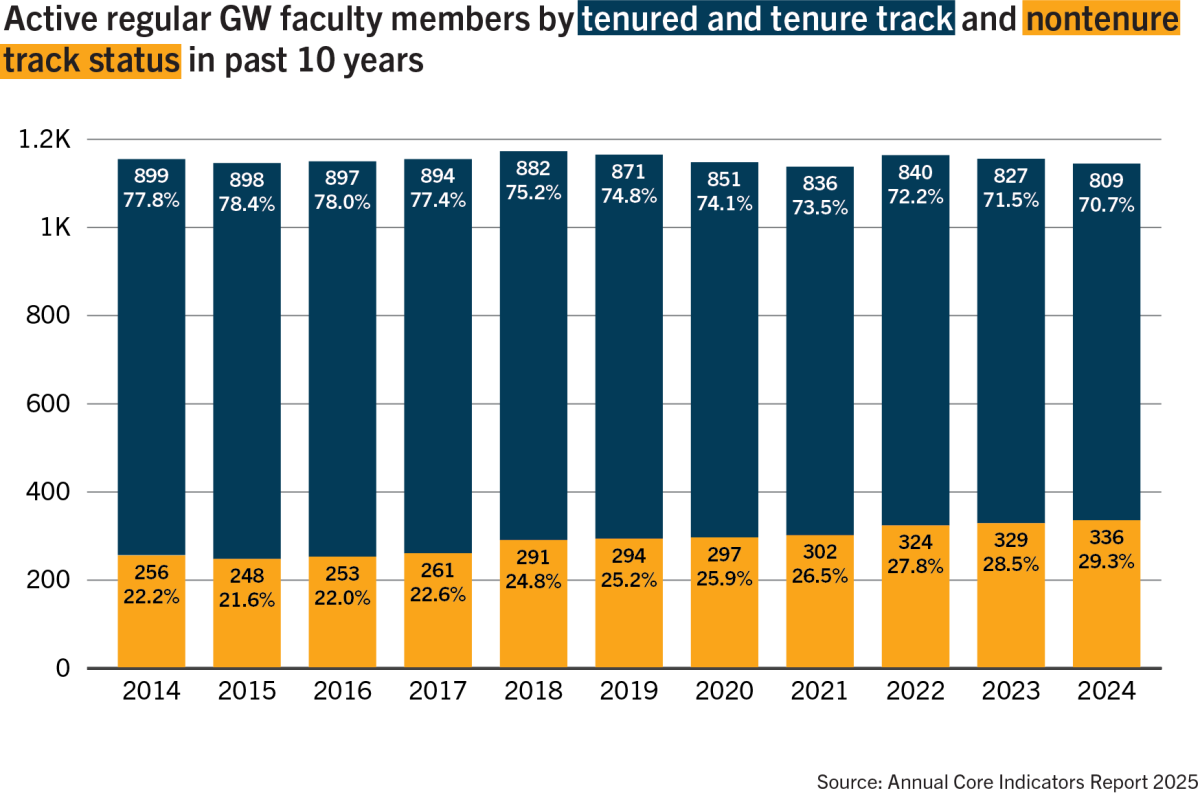

After tenured and tenure-track status for regular faculty dropped to a decade low this academic year, faculty said the steady decline in the number of tenured and tenure-line faculty could harm the University’s research mission.

Provost Chris Bracey presented data at this month’s Faculty Senate meeting that showed a steady reduction in tenure status for all regular faculty, falling from 77.8 percent of faculty in fall 2014 to 70.7 percent in fall 2024. Professors said tenured positions are “critical” to GW’s research mission because they provide job security to faculty, warning that officials’ replacement of tenured and tenure-line faculty with specialized faculty masks the waning tenure lines across the University that could stifle relationships between students and professors.

Regular faculty are full-time faculty with the titles of University professor, professor, associate professor, assistant professor and instructor, that are tenured or tenure-track, according to the Faculty Code. Academic tenure provides faculty with an academic freedom safeguard, according to the American Association of University Professors.

Specialized faculty are faculty on a renewable contract that do not hold a regular or tenured appointment at another university, according to the Faculty Code. Specialized faculty have a nine-or-12-month appointment at GW and have “contractual responsibilities” for research, teaching or service.

University spokesperson Julia Garbitt said “personnel head counts” in a given school are linked to a “variety of financial factors” and that schools with “strong” enrollment can financially support additional tenure or tenure-track faculty.

“As the University is a tuition-driven institution, strong enrollments within our schools can support additional investment, but it is important that the University does not over-invest in order to avoid future financial roadblocks,” Garbitt said in an email.

The University made $1.781 billion in operating revenue in fiscal year 2024, with tuition revenue making up 46 percent of the total operating revenue, according to a 2024 financial report.

The Faculty Code clause states that regular faculty in nontenure track positions should not exceed 25 percent in any school and that officials should tenure 50 percent of regular faculty in a given department. The requirement does not apply to the School of Medicine & Health Sciences, the School of Nursing, the Milken Institute School of Public Health and the College of Professional Studies, according to the clause.

The Faculty Code does not present a consequence for departments or schools that fail to meet the minimum threshold for tenured or tenure-track faculty.

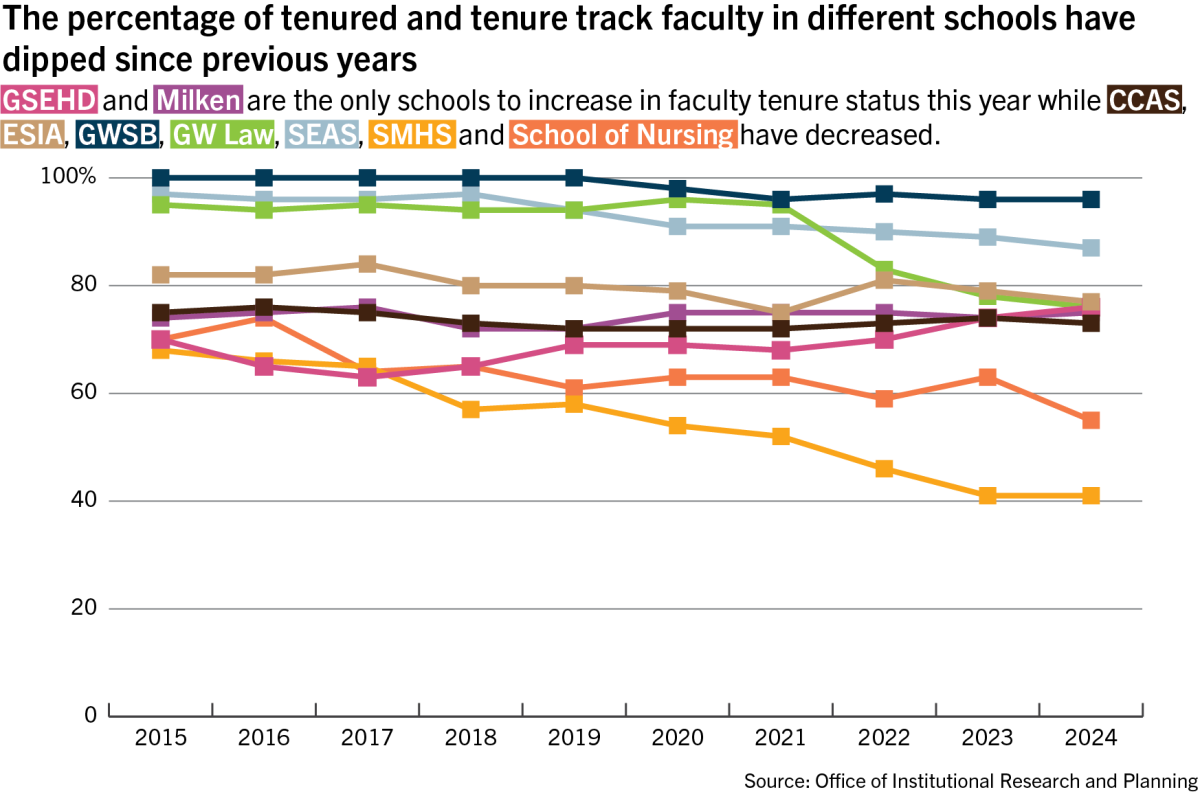

The Columbian College of Arts & Sciences fell short of meeting the 75 percent tenure rule for the seventh year, according to the annual core indicators report presented earlier this month. The Graduate School of Education and Human Development met the 75 percent tenure threshold for the first time within the last decade, according to the report.

In 2024, there were 7,702 total students enrolled in CCAS, the largest school at the University, and 958 total students enrolled in GSEHD, according to the enrollment dashboard.

Tenure status for all regular faculty fell from 71.5 percent in fall 2023 to 70.7 percent in fall 2024.

Garbitt said the “strategic addition” of tenure-track faculty lines across the University is a “critical consideration” for GW’s fiscal plans and scholarly endeavors. She said the University completes “analyses” each year to determine compliance with Faculty Code.

“Tenured faculty are crucial to the success of our GW community, and are at the heart of the University’s aspirations of achieving preeminence as a comprehensive global research institution,” Garbitt said in an email.

The last time the percentage of tenured or tenure-track regular faculty within CCAS met the threshold set by the clause was in fall 2017, with exactly 75 percent of regular faculty being tenured or on a tenure-track. In fall 2024, 73 percent of the school’s regular faculty were tenured or on a tenure-track.

The School of Business, the Elliott School of International Affairs, GW Law and the School of Engineering & Applied Science have all met or exceeded the 75 percent threshold every year for the past decade.

Faculty senators earlier this month raised concerns about the continued decline of tenured and tenure-track faculty and said the trends could ultimately shrink the number of tenured or tenure-track faculty to zero.

Similar conversations occurred during a Faculty Senate meeting in March 2024, where faculty senators said tenure-line faculty are essential for continuity within departments and help facilitate research, which can boost the University’s appeal and image.

Heather Bamford, a faculty senator and a professor of Spanish literature who is tenured, said officials are replacing tenure-track positions with “contingent” faculty who she said are “inadequately compensated.” She added that officials may not be creating new tenure lines because of “perceived cost savings” for the University.

“Tenure-track positions, which require work in the three areas of research, teaching, and service, are relatively expensive and are increasingly being replaced by contingent positions at many universities,” Bamford wrote in an email.

For the 2023-24 academic year, the law school offered the highest average salary for tenure-status faculty with the title of professor at $290,812, according to the 2025 core indicators report. GSEHD had the lowest average salary for tenure faculty with the title of professor at $141,708.

CCAS had the lowest salary for nontenure status faculty holding the title of professor, with an average salary of $143,312 in the 2023-24 academic year. Milken had the highest average salary for nontenure faculty with the professor title at $180,521.

Bamford said all GW faculty deserve proper compensation regardless of tenure status, but the 75 percent mark is a “problematic measure” of the University’s commitment to tenure because officials calculate faculty tenure percentages using only regular faculty, meaning that the changes in the number of specialized faculty are not represented in the ratio.

She said for the “actual health” of tenure status to be represented, the denominator for the ratio of tenure-line faculty to nontenured or nontenure track faculty should include all full-time faculty, both regular and specialized.

Bamford said she hopes that when a tenured or tenure-track faculty member leaves the University, officials fill the position with a tenure-line faculty member.

She said she also hopes officials create new tenure lines across various disciplines, like those which focus on teaching undergraduates and “significantly impact” the student experience through “deep work” in critical thinking, reading and writing.

Garbitt declined to comment on whether officials are replacing tenured or tenure-track faculty positions with specialized faculty. She also declined to comment on whether it is more cost-effective for the University to replace tenured or tenure-line faculty with specialized faculty.

Bamford said tenure is critical to the University’s research mission and to preserving the “high level of scholarly activity” that caused the Association of American Universities — an invite-only organization of 71 leading research institutions — to invite GW to join in 2023.

Bamford said it is difficult for faculty to produce “high impact” yet potentially “risky” scholarship without tenure status because of a mix of high workload and low compensation with the potential risk of being fired.

In April 2023, faculty senators amended the Faculty Organization Plan to add two nonvoting delegates from CPS to the Faculty Senate — changing the requirement that faculty needed to have tenure to serve on the senate, with an exception for SMHS.

Faculty senators amended the resolution to make the CPS seats nonvoting positions due to concerns that the college’s representative would not speak out against administration out of fear of retribution due to their lack of tenure, a CPS official said last May.

“I’ve tried when working in contingent faculty positions and in tenure-track positions with a high teaching load, and it is not feasible,” Bamford wrote in an email. “This is largely due to time constraints, inadequate research funding, and the fear of being fired. Academic freedom is a major and very literal factor — and it is the reason I can speak to these issues openly.”

Philip Wirtz, a faculty senator and professor of decision sciences and psychological and brain sciences who is tenured, said officials in schools like CCAS should tenure all regular faculty positions so the school reaches the 75 percent threshold.

Tenure status offers faculty the “needed protection” to explore new and potentially unpopular thinking, Wirtz said.

“It is a real disincentive to the exploration of out-of-the-box lines of thought if, by engaging in such exploration, you could be bending out of joint the nose of someone influential enough to cost you your job,” Wirtz said in an email. “Tenure protects against that, thereby allowing potentially unpopular out-of-the-box lines of thinking to be explored.”

Denver Brunsman, an associate professor of history and the chair of the history department, said tenured faculty add stability to course curriculum and offerings for students.

He said that in his department, students are required to work with a full-time faculty member to complete their senior thesis, which encourages students to have close and prolonged relationships with tenured faculty.

“We deeply appreciate and value our part-time instructors, but, ideally, students will connect with full-time faculty during their early course work and develop relationships that will continue through the senior thesis,” Brunsman said. “As the number of full-time faculty diminish, this standard is harder to maintain.”