Two weeks ago, President Donald Trump’s administration laid off roughly half the employees of the Department of Education, a move touted as a “significant step toward restoring the greatness of the United States education system.” It was certainly a significant step: Last week the pressure intensified, with President Trump’s executive order instructing Education Secretary Linda McMahon to begin closing the department. The ultimate goal is clear: to shift the department’s activities to other agencies and kill remaining programs or devolve them to states and local districts. Whether and how this action survives legal challenge — the department was created by Congress and would have to be eliminated by Congress — its intent signals a potential sea change in American education, with damaging and long-lasting consequences.

As one who has been involved in education policy and research for about 40 years, the last 15 of them here at GW, I believe we are experiencing a uniquely daunting set of challenges. I am glad to share in this commentary some personal reflections and perspectives on the current moment, which do not necessarily represent institutional positions of the University. Here I focus on the status of the department as a federal agency, a good starting point to understanding the bigger picture we are facing.

The Department of Education was created in the final days of the Carter administration in 1979, amid partisan debate. Key Democrats, including Joseph Califano and Albert Shanker, opposed the idea of separating the “E” from the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, but the plan survived. It was neither the first nor, obviously, the last time the existence of a federal education agency was the subject of heated controversy. Just one year after President Andrew Johnson signed the first bill establishing the department, its status was downgraded to “Office” in 1867. But that “office” played an important role over the next century, tasked mainly with “collecting such statistics and facts as shall show the condition and progress of education in the several States and territories…including at schools for newly emancipated African American children…”

Its reincarnation in 1979 seemed short-lived. President Ronald Reagan vowed to abolish it, but in the wake of arguably the most powerful report of the genre in U.S. policy history — which declared that we were “A Nation at Risk” — the agency survived. Since then, it has ably and nobly led the country’s efforts to enhance educational opportunities and life chances for disadvantaged youth, hold states and localities accountable for the provision of educational resources to students with special needs, enforce federal civil rights laws, manage the financial aid system that opens doors to millions of college-bound students and provide reliable data on the condition of teaching and learning across our system of public education.

The department’s 2025 budget request was $82 billion and historically has been in the range of 2 percent of the total federal budget. The federal share of funding for K-12 schools is about 14 percent, with the remainder covered by states and local governments. In addition, the department has been responsible for managing approximately $1.5 trillion in student loans.

Given that so much of education is managed and financed at the state and local level anyway, why is the effort to kill the federal role so wrong? As I’ve written elsewhere, just when data pointed to the disastrous effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on average student performance, came news of a calamitous drop in U.S. scores on international tests, with depressing evidence of widening gaps between majority and minority students. This downturn is largely due to the pandemic, following a half-century of progress during which time the federal role grew substantially. It is simply disingenuous to argue that recorded gains in achievement for all students and the shrinking of gaps would have been greater without sustained national investment. There are imperfections in the operation of our bulky bureaucracy, but what signal is sent by having the federal government withdraw just when the national will is needed to rebound from the recent decline? Perhaps most importantly, we need to ask about one of the federal government’s principal responsibilities, namely enforcing civil rights laws: Will we be better off ceding that task back to states and districts? Will “states’ rights” become “national wrongs,” again?

At the practical level, the Trump plan seems to involve complex logistical and programmatic shuffling without any proof of increased efficiency. For example, will the Department of Health and Human Services be ready to manage the Title I program for disadvantaged youth? Similarly, there’s no evidence that the Small Business Administration, with little or no experience in tuition assistance, will do a better job managing loans that determine the future of millions of students and their families. Another terrible loss will be felt by researchers — but also policymakers at all levels — if programs such as the National Assessment of Educational Progress, considered worldwide as the gold standard in educational measurement, are eliminated or transferred to an agency with no expertise in the workings of our school system. Ironically, the administration’s rationale for closing the agency is that our school system is underperforming — an allegation based on their interpretation of data collected by the department they want to eliminate.

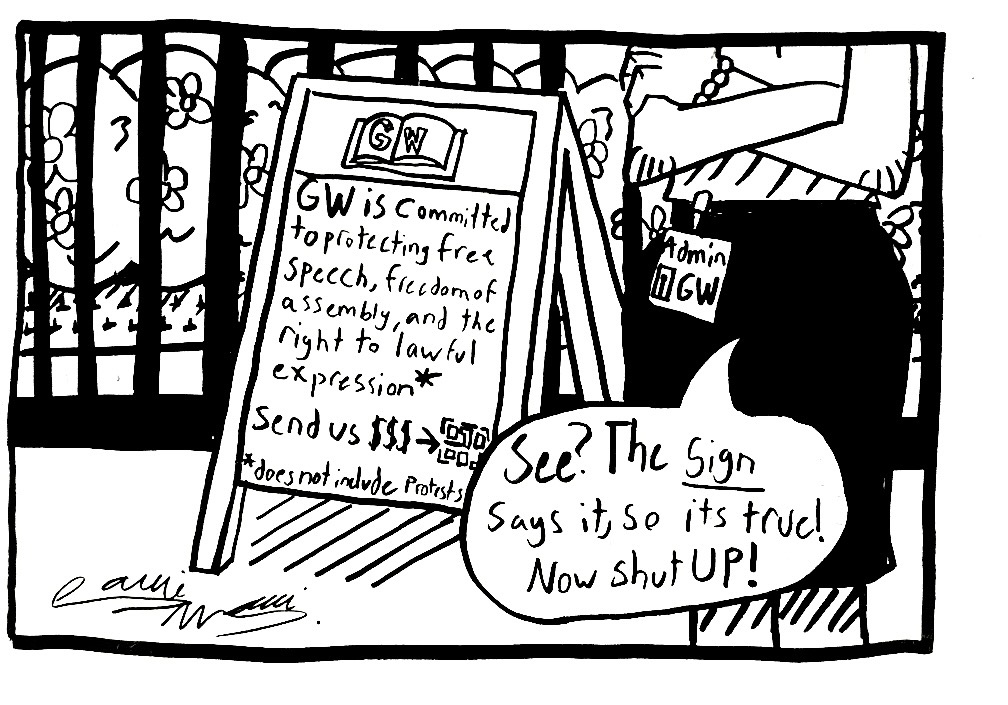

While these plans are implemented and litigated, and thousands of dedicated public servants are subjected to insulting accusations, my optimism derives from the dedication and accomplishments of our community. To my colleagues in the Graduate School of Education and Human Development, thank you for your amazing research and unflagging engagement with current and future educators. You model the meaning of “making a difference” in the lives of children and adults, for whom investment in education is the most significant determinant of improved life chances. We adapted as a community during the pandemic, and we can again demonstrate our steadfast will by focusing on our work, buoying our students and supporting one another. Likewise, the GW administration, trustees, alumni, donors and friends are demonstrating abiding commitment, standing with our GSEHD faculty, staff and students and reaffirming the mission of education as a public good. As the largest educational institution in the nation’s capital, with a globally distinguished school of education, our obligation now is to combine knowledge, hope, resilience, and yes, even some optimism, as we pursue continued excellence in all our endeavors.

Michael J. Feuer is a professor and the dean of the Graduate School of Education and Human Development.