Walter Lippmann ruined political science for me.

It’s a tad ironic because Lippmann, the predominant left-wing intellectual of the mid-20th century, is probably my favorite writer I’ve read in my undergraduate career. I even listed him as my “intellectual hero” on a job application that required that answer recently. But as admittedly pretentious as having an answer to that question at the ready is, I’d argue I have a good reason for it — in his 1913 book “A Preface to Politics,” Lippmann wrote the two sentences that changed how I look at university classes.

“Marx saw what he wanted to do long before he wrote three volumes to justify it. Did not the Communist Manifesto appear many years before ‘Das Kapital’?”

In other words: Every writer has their ideas that they can condense into a couple pages but then, like Marx, they go out and write thousands of pages stuffed full of stats to justify them. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the long “Great Book” format — I really liked reading “Capital,” and Lippmann put out a few lengthy works himself. But his point got to an issue I hadn’t realized had plagued me in college: the idea that just because a social science study has some backing doesn’t mean it’s not influenced by one person’s preconceived ideas.

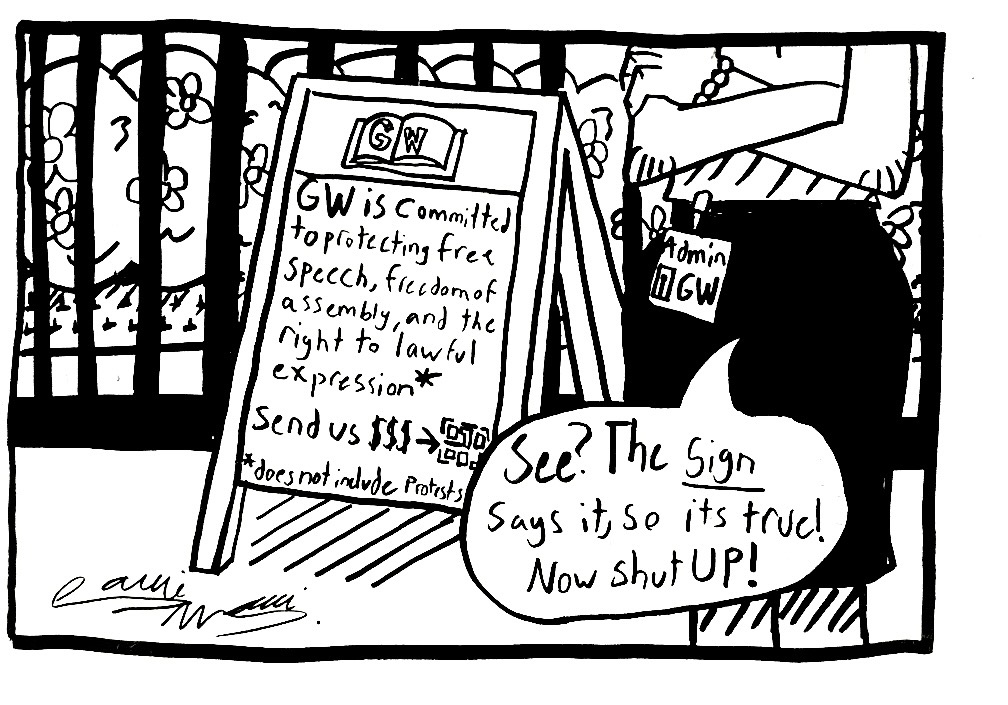

As a political science major, so many of my class readings in my chosen field were these sorts of studies, where a given researcher argued that a political system worked in a certain way and justified their findings with a study or case in history. The expectation in that class then became that these studies were right. Rather than having a discussion about the pros and cons of the ideas, the findings of a given work were expected to be dogmatically accepted so they could be repeated on an exam. After all, there was a study backing up those ideas, so they must be right. Right?

But in reality, the fact that someone penned a study doesn’t make that study good. Take one of the foundations of most American political science essays: the idea that Congress has an institutional interest in its own power and thus will act beyond party lines to prevent the president or Supreme Court from encroaching on legislative territory. Political scientists use that idea to spin off all sorts of concepts about how the three branches of government limit each other’s power, many and many of which I’ve been forced to regurgitate on exams. Even the most passing glance at how President Donald Trump has been able to steal away core legislative abilities like the power of purse, Congress’ exclusive ability to tax and spend, without so much as an attempt by congressional Republicans to stop him should put those theories to rest.

It’s entirely possible that some political scientists will take the findings of the early parts of Trump 2.0 and create a brilliant study that recontextualizes the role of Congress in light of those developments. But who’s to say that a decade from now senators might stop acting based on their party and instead based on what college football team they root for? That example is so apolitical that it seems silly, but if you told the political scientists behind those aforementioned studies that senators would act based on party and not institutional loyalty, well that’d seem just as ridiculous. All these writers are people with ideas about how the world works. They just happen to be good at arguing in favor of their ideas, but we should all take the time to think about how we’d counter their cases instead of just blindly embracing them. There’s been times when we’ve debated topics in classes, but for the most part the key to success has been an ability to repeat what a study says on a test.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t read these works. I’m saying we need to approach them as what they are: theories that might have good evidence in their favor but still should be debated and discussed rather than instantly accepted. That’s especially true when it’s so easy to plug a few words into Google and find any study that proves a point you’re trying to make when it’s just as easy to find a different study that makes the opposite point. Source: a 2021 Nature article I found as the first thing that popped up when I Googled searched “study on availability of studies.”

I’ve written in these pages before that “Almost everything I’ve learned in college I’ve read.” Let’s just remember to think and question when we’re doing those readings, too.

Nick Perkins, a senior majoring in political science, is the culture editor.