Professors of Middle Eastern studies and a White House economics reporter discussed the complex nature of sanctions at the Elliott School of International Affairs Thursday.

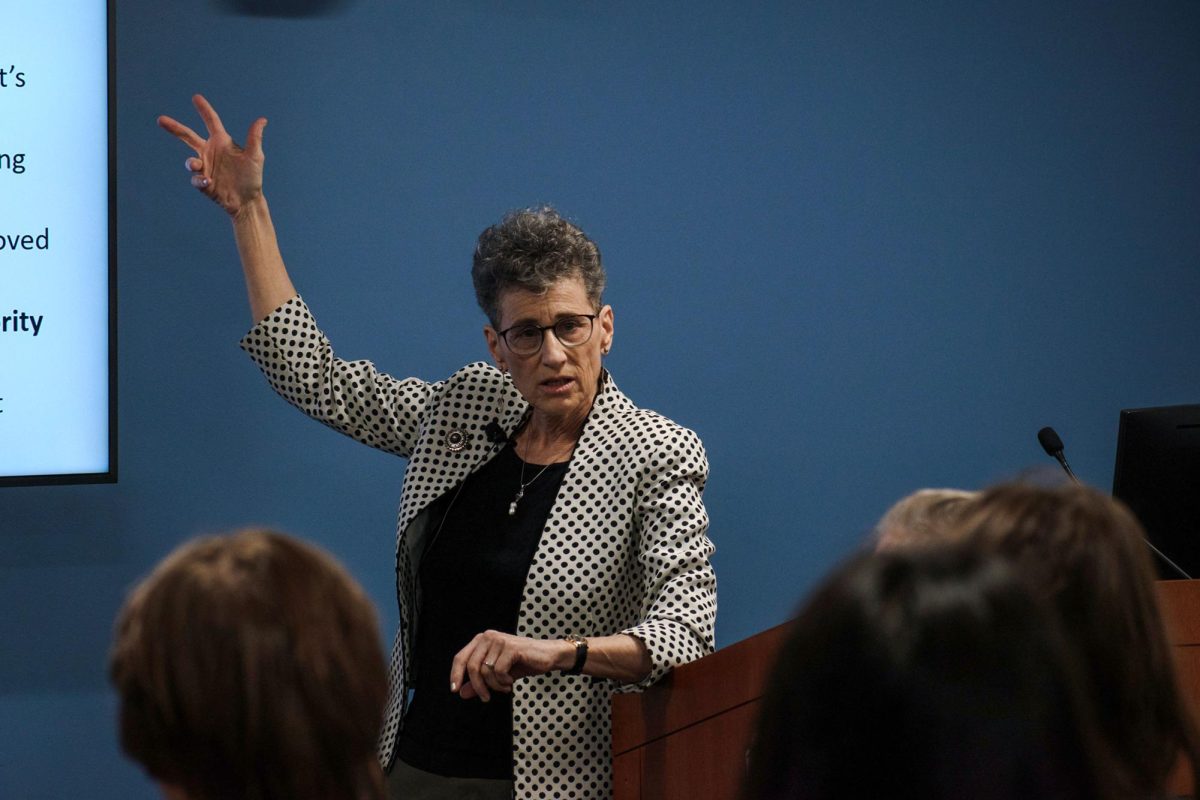

Narges Bajoghli, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, and author of “How Sanctions Work: Iran and the Impact of Economic Warfare,” and Jeff Stein, the White House economics reporter for The Washington Post, examined the implementation, geopolitical consequences and effects of U.S. sanctions on countries like Iran, Russia and China. Sina Azodi, a professorial lecturer of international affairs, moderated the panel, hosted by the Institute for Middle East Studies.

Stein said sanctions, a foreign policy tool that seeks to penalize unethical business behavior or governmental misconduct, are “incredibly easy” for U.S. presidents to impose on foreign countries, organizations or an individual person. He said sanctions are imposed when the U.S. Treasury Department decides that a person, country or other entity poses a degree of “threat” to America’s national security, economy or foreign policy.

He said the definition of sanctions is “broad” and that it has allowed America to become an “unchecked financial superpower” in the 21st century because presidents are able to impose sanctions by their own discretion.

Stein said the consequences of sanctioning Iran, one of the “most heavily sanctioned” countries by the U.S. due to it’s violation of treaties surrounding its nuclear program, are that sanctions sometimes backfire when Iranian-Americans in the U.S. have trouble getting their assets out of Iran because of the sanctions. He said eventually the Iranian government ends up possessing the Iranian-American’s assets, effectively exploiting the sanction.

“The U.S. government is like, ‘How do we punish Iran’s government?’ Right?” Stein said. “That’s the point of this, and what the effect of what they’re doing is, is to give the Iranian government more money.”

Stein said there is a list of “specially designated nationals” created by the U.S. government that consist of people who are not being accused of a crime, but are sanctioned and put on the list to make it illegal for anyone to do business with them. He said this often causes the people on this list to be cut off from the global financial system and lose the ability to access bank accounts or critical imports.

“These are grave consequences, and yet the evidentiary standard to effectuate that punishment is much lower than it is in a court of law,” Stein said.

Stein said the Biden administration has tried to address the humanitarian consequences of sanctions — the rise in prices and damage to the economy — by issuing “licenses” that allow sanctioned nations to import certain things like medicine or food. He said businesses are sometimes wary to work with sanctioned countries because if they violate the license and import something they were not supposed to, not only does the country face consequences but the business does as well.

Stein said hesitancy from countries has caused the tool that was meant to aid against the humanitarian impacts of sanctions to be unsuccessful.

“That has resulted in an increased, a sort of stepped-up cessation of trade with sanctioned regimes despite the formal attempts of the Biden administration to carve out humanitarian exemptions,” Stein said.

Bajoghlis said sanctions were created after World War One when world leaders were looking for a tool to hold geopolitical adversaries accountable for their actions while avoiding military combat.

“So sanctions was seen as something that lawyers and bank financiers could do behind their mahogany desks, and it seemed to make a lot of sense, because it was not going to lead to dead bodies,” Bajoghlis said.

Bajoghlis said although sanctions from the United States have increased by 900 percent in the 21st century, there is very little research on what sanctions achieve in the target country. She said the goal of sanctions is to pressure the elite in the country to make political or societal change, but in doing that there is no way to avoid the damage that is done to the civilian community.

She said the outcome of these sanctions is that businesses move to “black and gray” markets and prices “begin to shoot up.”

“The main arm of sanctions is that it causes widespread economic carnage on the civilian population, and there is really no way to separate the impact on the elite versus the impact on the population,” Bajoghlis said.

Bajoghlis said sanctions are often “vague” and “opaque,” and are written by lawyers in a way that allows for broad interpretation and over-compliance by companies and financial institutions. She said critical evaluations of the humanitarian and economic impacts of sanctions are needed.

“We’re not really taking stock of the fact of, are sanctions working in the ways that we want them to be working?” Bohoghli said.