Frozen ground in the Arctic is sinking at an accelerated rate due to rising temperatures, per a GW study published this month by researchers in the Department of Geography and Environment.

The study, led by Dmitry Streletskiy, a professor of geography and international affairs, showed that permafrost — soil that stays frozen for more than two years — that is melting because of rising temperatures due to climate change is causing land sinkage in the Northern Hemisphere at a rate of up to 3 centimeters per year. The study states that land shrinkage rates are higher in areas impacted by wildfires and human-related activity, like road construction, specifically in countries with high latitudes.

“On a global scale, we showed that it is a primarily climatic-driven phenomenon that occurs in natural environments. Now, on top of climate-driven changes in areas of economic industrial activities, subsidence rates were higher because of disturbances,” Streletskiy said.

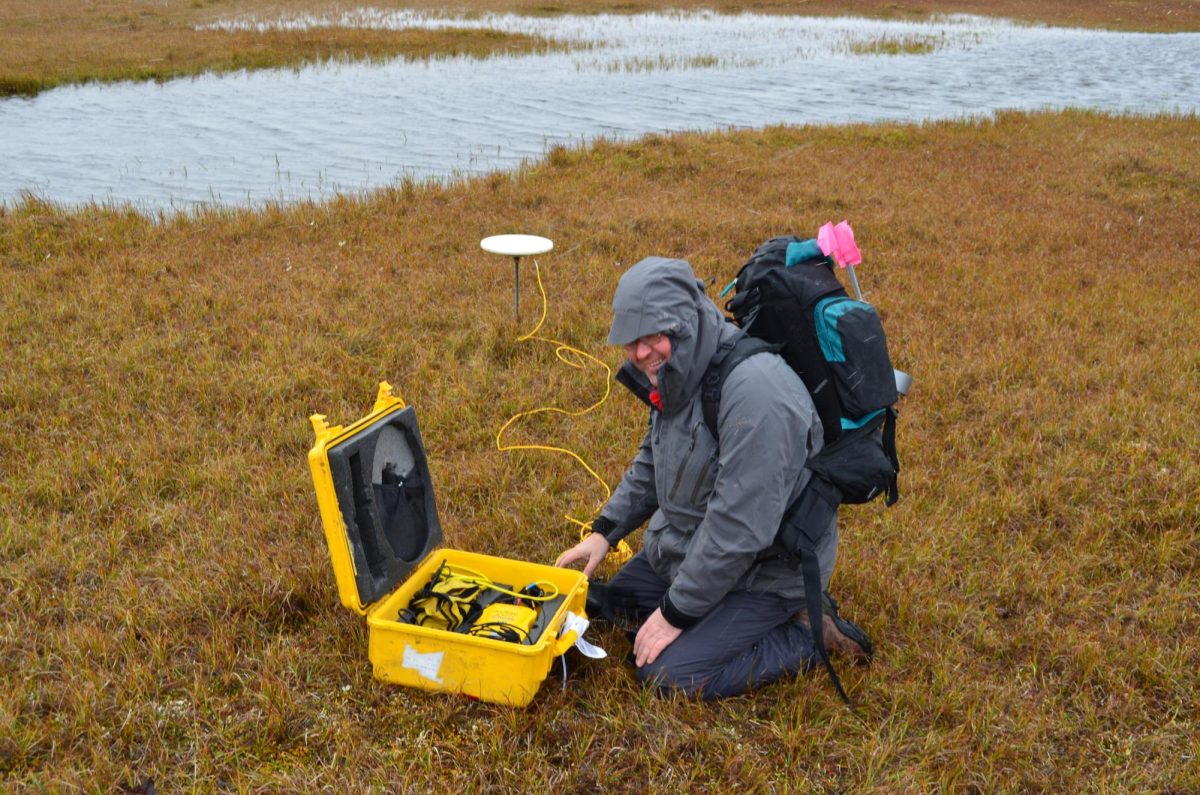

Land sinks due to melting permafrost, also called thaw subsidence, refers to the gradual decrease in ground levels as ice within the permafrost melts. Researchers used field observations, remote sensing technology and numeric modeling to record the rates at which thaw subsidence is occurring in North America and Eurasia, according to the study.

The study primarily focused on countries with high latitudes, like Russia and the Scandinavian countries, which are the most vulnerable since they are close to the Arctic. The study found land in areas with less ice content in its soil, like the western Yamal Peninsula in Siberia, were sinking up to 2 centimeters per year and areas with higher ice content, like the Lena River Delta in eastern Siberia, were sinking up to 3 centimeters per year.

Nikolay Shiklomanov, a professor of climate and environmental change and researcher on the study, said a concern related to thaw subsidence is the emission of carbon dioxide stored within vegetation in the permafrost into the atmosphere. 1460 to 1600 billion metric tons of organic carbon is stored in permafrost around the Arctic, about twice the amount of carbon in the atmosphere today, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Shiklomanov said the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere could create a feedback loop, where increased global temperatures from carbon dioxide in permafrost soils contribute to the release of more carbon dioxide.

“In terms of organic carbon, most of it is in vegetation,” Shiklomanov said. “If this is just taken out, it begins to decompose very quickly, and decomposition returns carbon back to the atmosphere, which can potentially serve as a major feedback to the climate system.”

The Natural Resources Defense Council states that 10 percent of permafrost in the Northern Hemisphere has melted since the early 1900s due to rising temperatures. Even if the targets to decrease emissions by 43 percent by 2030 set by the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change were met, 2.5 million square miles of permafrost could melt, according to the organization.

Streletskiy said in response to these concerns, the international community must cooperate to monitor thaw subsidence despite geopolitical tensions.

“Arctic research comes with very high logistical and operational costs, and now on top of that, we have a complicated geopolitical association which limits data exchange. But in an ideal world, this is a process of happening,” Streletskiy said.

Julienne Stroeve, a professor of polar observation and modeling at University College London, said human structures, like infrastructure and habitation are vulnerable to destruction and damage due to the effects of melting permafrost, like coastal erosion and thaw subsidence.

“They’re already dealing with permafrost thaw in the Arctic and having to redo infrastructure and entire villages are going to have to get moved,” Stroeve said.

Stroeve said another effect of melting permafrost is the release of chemicals and viruses previously frozen in hibernation, an occurrence that puts natural ecosystems and humans at risk. In 2016, an anthrax outbreak in Russia was thought by scholars to have been a result of melting permafrost in the Arctic releasing the pathogen into the air.

“There’s a lot of mercury also stored in permafrost, so that’s a big contaminant,” Stroeve said. “There’s a whole host of things. Then of course there’s concerns about different viruses that have been frozen for a long time.”