I visited America for the first time last summer — or, at least, I visited Butte, America, for the first time.

Butte is a small, declining mining town with an old toxic copper mine pit on the western end of heavily Republican Montana. The town has adopted the lofty nickname not just of “Butte, Montana,” but “Butte, America,” implying that the fifth-largest city in the eighth-smallest state was somehow worthy of the recognition we give to the most famous cities in other countries. Paris, France. London, England. Butte, America.

The first time I saw the gaudy highway signs with massive red letters along I-90 welcoming me to “Butte, America,” journeying from my home in Billings where I worked on a Senate campaign, I thought it was weird. Sure, the whole nickname was probably in part a knowing ironic riff on the reputation of Butte, the place where FBI and George McGovern campaign screwups were sent to have their careers rot. But still, the idea that a Montana town with 30,000 people somehow deserved the implied title of the ultimate, defining American city was laughable coming from D.C. — the nation’s capital and the home of nearly every famous quintessentially American symbol.

Yet at the same time, the idea that Butte should be called Butte, America, made sense because of what I was seeing out in Montana. The area is extremely Republican, and such symbols of America are the exclusive domain of the right. Almost every house has an American flag flying outside. Mount Rushmore, which in theory shows off our four greatest presidents to inspire as much national pride as possible, is a day’s drive from where I lived in Billings. The fact that these heavily conservative areas embrace these symbols implicitly turns them into the “real” America, and thus the party that represents the area as the “real” American party.

But the great irony is that all of these symbols that supposedly make the West the most patriotic part of the country are all reappropriations of D.C. monuments. The presidents who adorn Mount Rushmore did their work in D.C. — notably, George Washington University isn’t in South Dakota but the District. The Democratic Party needs to recognize the need for some form of patriotism to chart a path forward.

Perhaps the starkest example of the Mountain West’s attempt to claim patriotism with symbols from D.C. came when I trekked south to Cody, Wyoming, to see the town’s famed “Nite Rodeo.” The event is a glitzy spectacle, where rodeo riders from ages eight to 80 decked out in American flag-patterned cowboy hats compete to best wrestle horses and cows, with occasional jokes about gas prices sprinkled in. The rodeo makes its initial assertion of patriotism before the event begins, though after the nightly “Cowboy Prayer.” The evening’s host tries to emphasize the true Americanness of the event by reading a poem about 9/11, and leading guests, many of whom were visiting from Montana, in a performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” 9/11, which in part took place in D.C.; “The Star-Spangled Banner,” which was written about a flag currently hanging in D.C.

D.C. not leaning into its patriotic nature gives the political right extra legitimacy. Conservatives get to claim to represent the shining city on the hill, the idea of America, while they say the heavily Democratic District — where every symbol of America resides — and the left as a whole is against those ideas.

Democrats don’t need the same sort of Americanism that you see in Butte, Montana, the glamorized version of our country’s story, but they need some brand of patriotism. D.C. can’t determine the entire party’s stance on the amorphous concept of America, but the city is so dominated by Democrats and is such a site for political spectacle that the District is a natural starting place for this reclamation of patriotism by the left.

People in America like America, and they like people who like America. Just look at the president-elect: Donald Trump talks nonstop about the need to “Make America Great Again” and has already started crafting a (concept of a) plan for America’s 250th birthday in 2026, a massive celebration to come in Iowa.

If the left doesn’t reassert a claim to patriotism, Republicans will be more than happy to run away with being the party of America, a situation neither true nor particularly helpful to the future electoral success of Democrats. Case in point: When I was in Montana, the land of the patriot, the Democratic campaign I was working on lost. Democrats this year might have been warmer to the stereotypical ideas of the red, white and blue than in cycles past, but polls still show that Republicans drub their opponents in terms of who feels more “patriotic.”

Since the election, there’s been talk of the need for a new vision of the Democratic Party. Working to become the party of patriotism isn’t a complete basis for the political future, but it’s a start at a time when that change is really needed. Let’s not forget that the candidate who won the election two weeks ago was the one with “America” in their slogan, not the one who promised a continuation of some vague status quo.

The District can embrace the patriotic symbols within its boundaries while still providing critical takes on American history, ideals and the way the country often fails to live up to them. Hanging up an American flag or being proud of the fact that you live within walking distance from the Washington Monument doesn’t mean that you love every single thing the country or what George Washington did. But it reclaims those quintessentially American symbols that should “belong” to the left — after all, the history of this country is in many ways a history of continuous progressive movements prompting liberal change.

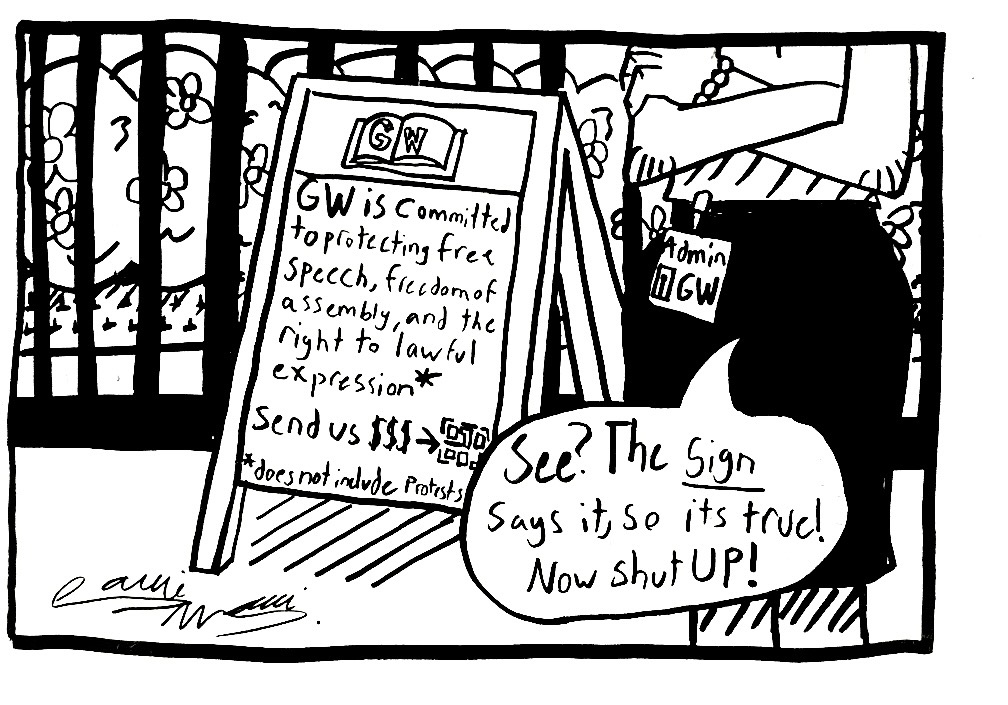

That reclamation has to start with the people closest to the Capitol, the White House, the Constitution, to America: GW students.

I’m not saying every single person on the left immediately needs to go wave an American flag. But there’s no reason that we should associate every single American flag we might see with conservatism. Those symbols of America can be a way to move toward something better and more progressive, a demand to live up to the ideals they promise — something they’ve been used to represent for decades. To have any shot of getting over the idea that patriotism is the exclusive domain of the right, we in the District need to own patriotism.

Nick Perkins, a senior majoring in political science, is the culture editor.