D.C. opioid overdose deaths are down significantly for the first time since 2018, according to data released on Sept. 19 by the D.C. medical examiner.

The D.C. Office of the Chief Medical Examiner recorded 196 opioid overdose deaths from January to June of this year — 60 fewer than the first half of 2023 — which experts and public health officials say suggests the total overdose deaths for this year will be significantly less than recent years. Experts said opioid deaths in the District have increased since 2018 when fentanyl flooded the drug supply and that there is disagreement about why this trend has slowed this year.

The data reported seven opioid overdose deaths in Ward 2, which encompasses Foggy Bottom, in the first six months of 2024 and 22 and 34 deaths in Wards 7 and 8 respectively. Black individuals made up 84 percent of opioid overdose deaths in the District and approximately 70 percent of deaths were of males, according to the report.

The data in the District reflects a national decline in opioid overdose deaths, with provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showing a 10 percent national decline in deaths this year as of April.

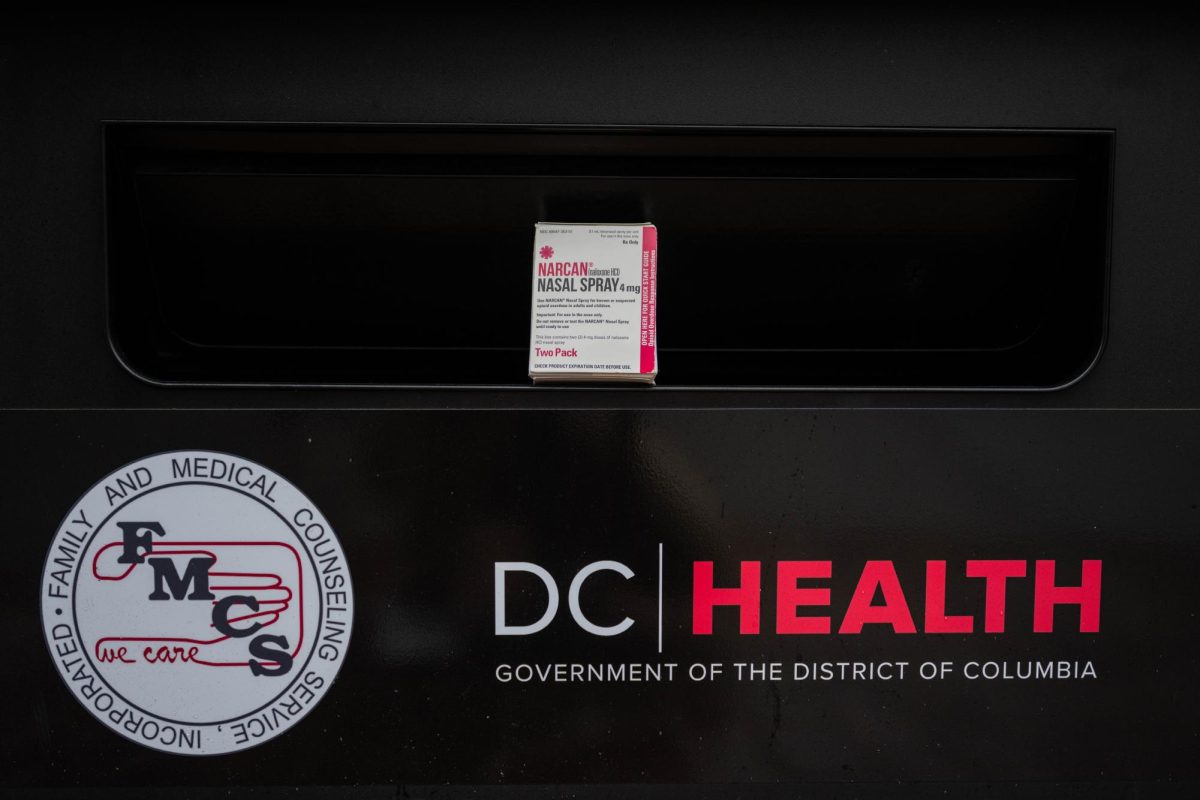

Mark LeVota, the executive director of the D.C. Behavioral Health Association, said experts do not entirely know what is causing the decrease but said the increase in prevalence of fentanyl test strips and access to Naloxone — a drug that reverses the effects of opioids — may be contributing factors.

“We hope that it will bear out, but it’s hard to say,” LeVota said. “This is still, unfortunately, an epidemic that’s killing too many of our neighbors, and we have to keep our foot on the gas and take it seriously. I don’t think we entirely know what’s making this happen.”

In April of last year, officials in the District installed six vending machines stocked with Naloxone and fentanyl test strips in Ward 6, 7 and 8, which historically have had the highest rates of opioid overdose deaths, according to data in the report.

LeVota said while fentanyl is prevalent in opioid deaths nationally, it is especially so in the District due to the prevalence of “street” drugs as opposed to prescription drugs in overdose deaths. The data states that 95 percent of opioid overdose deaths in 2024 so far involved fentanyl, which is higher than the national average of around 68 percent in 2022.

The data also reported a decrease in opioid overdose deaths involving xylazine, also known as Tranq, which is a veterinary sedative with nine deaths in the District involving xylazine so far in 2024. In all of 2023, there were 15 xylazine related opioid deaths. The report states that there has been an increase in the prevalence of xylazine in D.C. since 2020. LeVota said the “problem” with xylazine is that since it is not an opioid, Naloxone does not reverse its effects.

“So far, there’s not an on the street reversal agent that we can offer to people to reverse xylazine,” LeVota said. “The other thing that we know about xylazine is that xylazine tends to also cause some additional physiological damage to people who are using.”

LeVota said officials are also seeing an increase in the number of young Hispanic residents in the District that are dying from opioids laced with fentanyl. He said the increase is something to be “mindful” of because data typically shows older males having the highest opioid death rates.

“We are going to have to think about some different prevention strategies, as well as making sure we do all of the work that needs to be done in terms of harm reversible or harm reduction reversals of overdoses,” LeVota said.

LeVota said the higher number of deaths among the Black community is a result of the “legacy of racism” in the District where Black communities were not given the proper resources to curb drug use in comparison to white communities. LeVota said this reflects a trend where the opioid crisis only got national attention when it started showing up in prescription drug supplies and affecting white communities.

“In many parts of the country, the fentanyl crisis has been a prescription drug crisis, and that’s very much the case,” LeVota said. “Certainly the opioid crisis across the country really only gained broad public attention when it started to affect and led to more deaths for white people.”

Arianna Campbell, the founder and senior director of Bridge to Treatment, an organization dedicated to increasing access to emergency health care nationally, said opioid overdose deaths started increasing nationally starting in 2017 when doctors began overprescribing opioid drugs.

“We would like to think that we mitigated it by having access to Naloxone and access to buprenorphine, specifically so a medication to treat opioid use disorder that was normalized in our community, though it’s still unacceptable.,” Campbell said. “These are all preventable deaths.”

Campbell said she is “hesitant” to celebrate this apparent decline in deaths because the decline is just getting back to normal levels before the increase in 2017. She said there is still an “unacceptable” amount of people dying, but she is glad there are now less deaths overall.

“I’m always going to celebrate less people dying, of course, and I’m hesitant for any celebration, because the sheer numbers of people dying from overdoses has been alarming and unacceptable for so many years that I take caution with looking at these numbers right now,” Campbell said.