On a Tuesday night at Ford’s Theatre, Abraham Lincoln’s life flashed before his eyes.

The 16th president, wearing suspenders that pulled his pants nearly halfway up his torso, gazed up from the stage to the theater’s presidential booth — a luxury box suite draped with the American flag where almost 160 years earlier he was shot. Lincoln looked out to the audience, telling them how he remembered sitting there in April 1865, watching the play “Our American Cousin” before he saw a white flash of light, pulling him into a daze of his childhood years.

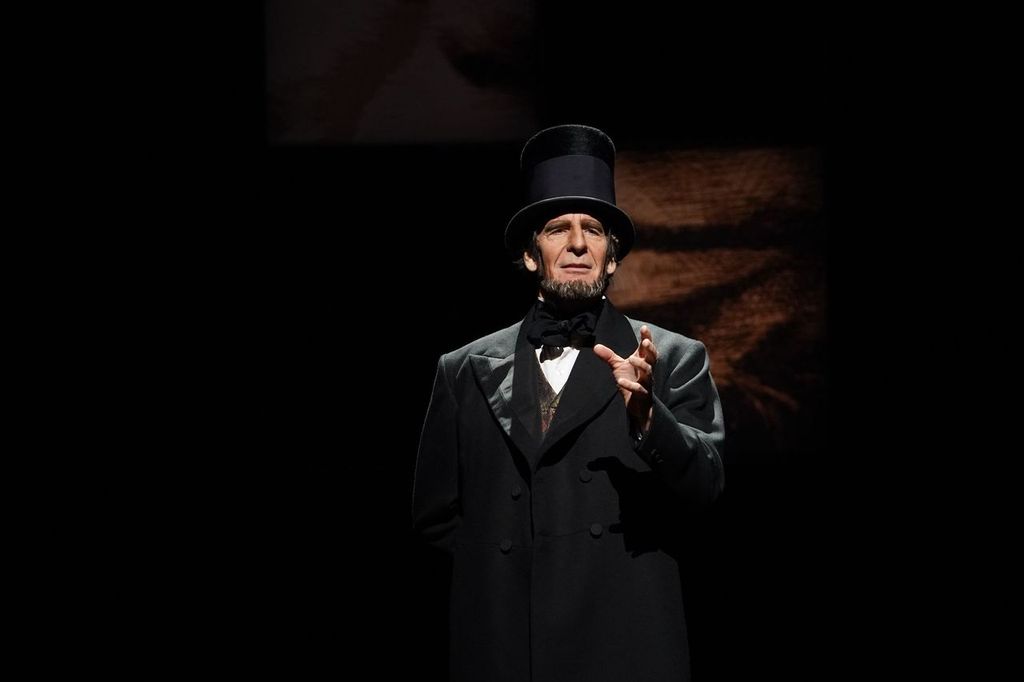

But Lincoln wasn’t really there. Instead, actor Scott Bakula was monologuing Lincoln’s life as the starting point for “Mister Lincoln,” a revival of a one-man play about the former president’s life running until Oct. 13 at Ford’s Theatre, the site of Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. The play transports audience members from his log cabin childhood in Illinois to the day he died, all through Bakula’s solo narration.

José Carrasquillo, the director of artistic programming at Ford’s Theatre and director of “Mister Lincoln,” said the play is from the late 1970s and opened in Canada before eventually coming to Ford’s Theatre in 1980. Carrasquillo said since Lincoln’s life and death is Ford’s “brand” and as Americans navigate the current polarized political climate ahead of the upcoming presidential election, he wanted to revive Lincoln’s memory to remind people of the character and moral compass of the “quintessential American president.”

“Our present and the past are kind of connected,” he said. “And my hope is that Lincoln’s message in the play and even understanding the momentous legacy that he left us may change one mind.”

Carrasquillo said the theater has put on shows centered around Lincoln before, but he wanted to feature this iteration of “Mister Lincoln” specifically because about 85 percent of the play is dramatic readings of the late president’s writings. He said the play’s textual basis paints a fuller and more factual picture of who Lincoln was for the audience.

“It allows an opportunity to portray someone who actually was depressed, who really was at war with his generals, who got angry,” he said.

“Mister Lincoln” touches on the broad contours of Lincoln’s anti-slavery, pro-Union ideology, often using direct quotes from writings and speeches like his famed Second Inaugural Address or his letters to his wife Mary Todd. Lincoln was considered a powerful orator, both then and now, and some consider him the best U.S. president due to his leadership of the country through the Civil War.

Seeing his speeches performed with thespian flair before a backdrop of pictures of the former president and pages of his writing brought his works to life more than reading them in a class. But save for those moments, Bakula’s Lincoln, who looks a bit like a waxy Hall of Presidents creation, is a goofy character.

At one moment, he turns the suspension of habeas corpus — which let the Union government more easily prosecute secessionists — into a stand-up comedy bit. Bakula confronts each imaginary member of the cabinet, and after loud speakers play each person’s “nay” vote, Bakula hesitates for a second to let the coming punchline hit the audience even harder.

“The nays are 7, the ayes are one — the ayes have it,” he said with a smirk to the audience.

The whole experience is quite charming. There is something endearing about seeing a venerated figure of American political history become a self-deprecating performer — even if there sometimes was a morbidity about the experience happening mere feet from where the real Lincoln died. “Mister Lincoln” deserves kudos for letting audiences see so many of the president’s famed words acted out while also containing maybe the funniest portrayal of Lincoln possible without devolving into pure parody.

Carrasquillo said a large part of the credit for that comedy goes to Bakula, who has a natural “wit” on stage. He said Lincoln also deserves some props for the play’s humor, since he had a self-effacing sense of humor in his writing. In the play, Bakula’s Lincoln riffs about how terrible he looks in comparison to his wife when recounting their love story.

He said “Mister Lincoln” as a one-man show, as opposed to other plays about Lincoln which include more characters, demanded more from Bakula since he didn’t have other actors to play off of, but it also let the duo flesh out Lincoln’s character more without distraction.

Lincoln did feel like a fully defined character, but sometimes seeing Bakula act out dramatic interactions while talking to himself felt a bit ridiculous. In one scene, an imaginary Republican powerbroker courts Lincoln to run for president, but with no one to act against, the audience is left seeing Bakula try to react to nonexistent propositions from an otherwise empty stage. The affair doesn’t quite reach the level of unintentional hilarity as Clint Eastwood talking to an empty chair during the 2012 Republican National Convention, but it sometimes distracted audiences from the rest of the show.

Jim Garrett, a senior tour guide at tour company Unscripted DC and a self-professed Lincoln assassination aficionado, said it is a “great idea” to put on a play about Lincoln during a “dysfunctional” period in American politics in which presidents haven’t been as “strong” as Lincoln.

Garrett said he is hankering to see yet another Lincoln play. After all, he said he’s been obsessed with the man and his death ever since he saw Lincoln’s bloody pillow in third grade while visiting the Petersen House across the street from the theater where Lincoln died.

“The pillow had this huge blood stain on it, and that’s what every third grade boy wants to see, big blood stains, and so that’s what got me hooked into the Lincoln assassination,” he said.

After Tuesday’s performance of “Mister Lincoln,” I was walking out of the theater toward the house where Garrett saw that very pillow. I held the door for an elderly man in a tan patchwork plaid suit jacket. The usher smiled at him as he walked out, and said he hoped the man enjoyed the show.

“The show, yes, but that part after, no!” the old man declared, referring to a brief thank you the director had given. I imagine if you had asked Mary Todd Lincoln what she thought of the first two acts of the April 14, 1865, performance of “Our American Cousin,” she’d have said pretty much the same thing.